By using this website, you agree to accept MoodChangeMedicine.com website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

April 22, 2014

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

Stress is a trigger of inflammation and mental disorders such as anxiety and depression. 1 Stress can be battles with your boss, being buried by bills or a pending a divorce.

Chronic stress causes Inflammation and can be very damaging to mental and physical health. Stress does damage through the repeated activation of the fight-or-flight mechanisms of the body called the HPA-axis, or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. This causes a cascade of biochemical events leading to hyperactivation of inflammatory proteins that are linked to depression, anxiety and a host of other conditions. 2

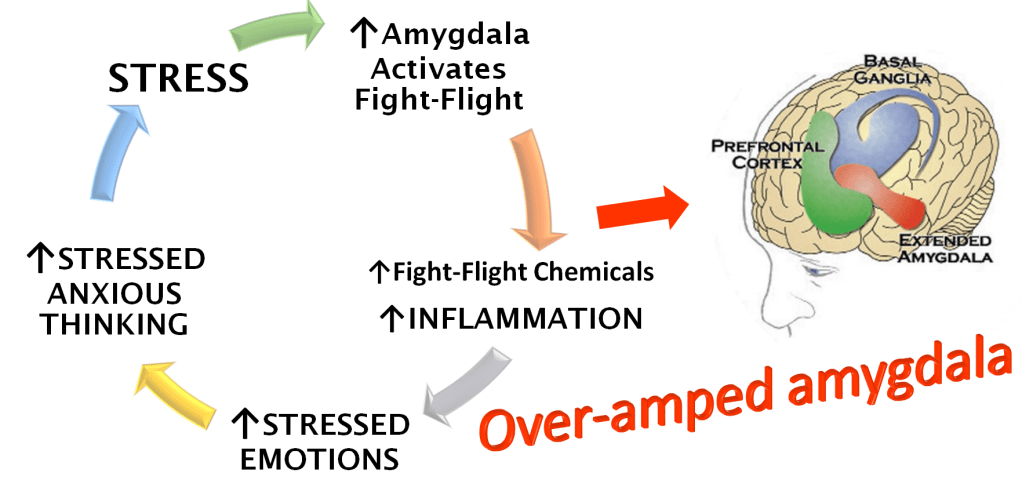

There’s a smoking gun in the brain that’s at the center of this vicious cycle, a sentinel whose job it is to keep us safe from threats: the amygdala.

“Emerging evidence suggests that the hyperactivity of amygdala neurons is a fundamental cause of chronic stress-induced anxiety disorder and depression,” scientists from the Laboratory of Fear and Anxiety Disorders explain. When life is pretty calm, the amygdala is in a calm state and does not get activated when low-levels stressors appear in our lives. However, when we are exposed to high levels of stress, the amygdala switches into high gear, a state where it is easily activated by even small stressors.

The Laboratory of Fear and Anxiety Disorders scientists explain: “Neuroimaging studies have shown that amygdala activation in patients with anxiety disorders is significantly higher than that in controls in response to the same stimulus, which is decreased after effective cognitive behavioral therapy.” And in patients with depression, there is not only higher levels of amygdala activation in response to emotional stimuli, but also higher levels of amygdala activation all the time regardless of whether they are exposed to provocative stimuli or not, the scientists said. 3

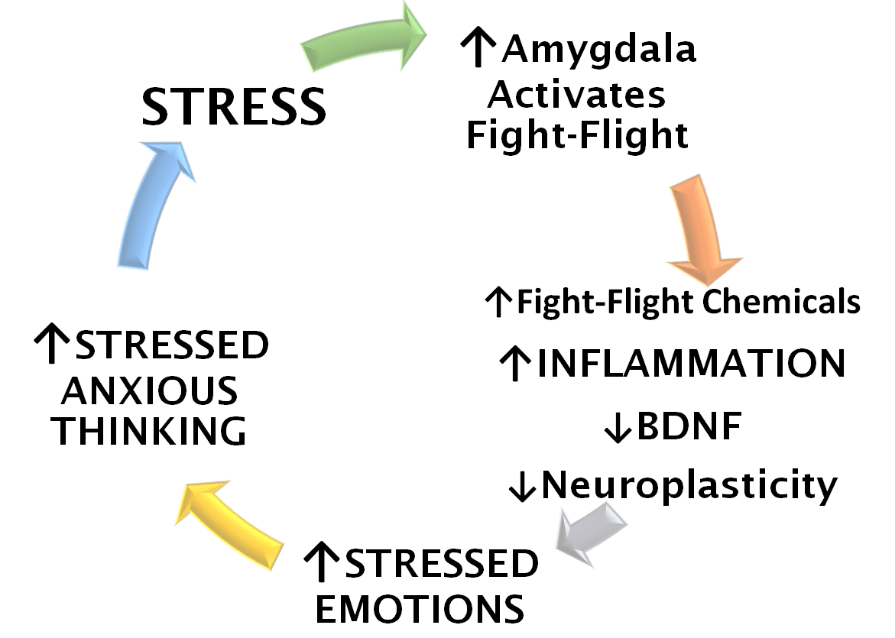

A vicious cycle is set off by stress, which triggers activation of the amygdala, which in turn causes the release of fight-or-flight response chemicals. These chemicals trigger more inflammation, which sets off even more activation of the amygdala. The process feeds on itself leading to a hyperactive amygdala that reacts to the tiniest of stimuli and creates anxiety and depressive mood. 4

Stress, stressed thinking and the inflammation they cause are at the heart of a vicious cycle of repeated activation of the amygdala. Stress and stressed thinking trigger the amygdala to turn on the fight-flight threat system that protects us from danger. The fight-or-flight system causes the release of fight-or-flight chemicals like cortisol and adrenaline. These chemicals spur inflammation in the brain and body. Once inflammation gets going, it puts the amygdala on high-alert so it is more attuned to detect signs of danger and hence more sensitive to stress. When the amygdala enters high-alert status, it ramps up our body’s fight-or-flight biology sparking an upsurge in anxious feelings and sensations. This powers anxious thinking.

As the amygdala gets continually reactivated, more and more fight-or-flight chemicals flood the system leading to a further increase in inflammation. The higher the levels of inflammation in the brain, the more sensitive the amygdala becomes to stressors, which it sees as potential threats to safety. It becomes increasingly more reactive—more easily activated so that even minor stressors can amp up anxiety. Things that weren’t causing anxiety before now trigger us. As the amygdala is hit by ever increasing levels of inflammation, it amplifies an ever-spiraling vicious cycle of anxious thinking and feelings—which are more easily set into motion by constantly living in fight-or-flight.

We can end up with a hyperactive, overamped amygdala that can react to even the tiniest of stressors as we become ensnared in unrelenting, escalating cycles of stress, inflammation and anxiety.

Stress has been found to cause potentially reversible atrophy in brain regions of depressed people that are responsible for mood regulation 5 including the hippocampus. 6 Atrophy is also seen in the prefrontal cortex of depressed patients. Stress induced damage and decreases in the regenerative capacity also caused by stress “could be relevant to hippocampal atrophy” according Robert M. Sapolsky distinguished professor of neurobiology at Stanford University, and Department of Neurology, Stanford University School of Medicine. 7

Stress significantly changes the levels of a substance called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which heals neurons in the brain and promotes neuroplasticity. Such changes in BDNF are implicated in the development of anxiety and depression.8, 9

Stress is a one-two punch to the brain. When stress sparks inflammation it has numerous ways to interfere with the brain’s regenerative capacity—its neuroplasticity. Inflammation leaks in between brain neurons throwing a monkey wrench into the brain’s neural circuitry and at the same time stress significantly decreases BDNF, which could help restore the damage done to neuroplasticity. 10, 11, 12

The stress-induced reductions in BDNF diminish the ability to regenerate brain tissue damaged by inflammation just when it is needed to recover from stress, anxiety and depression.

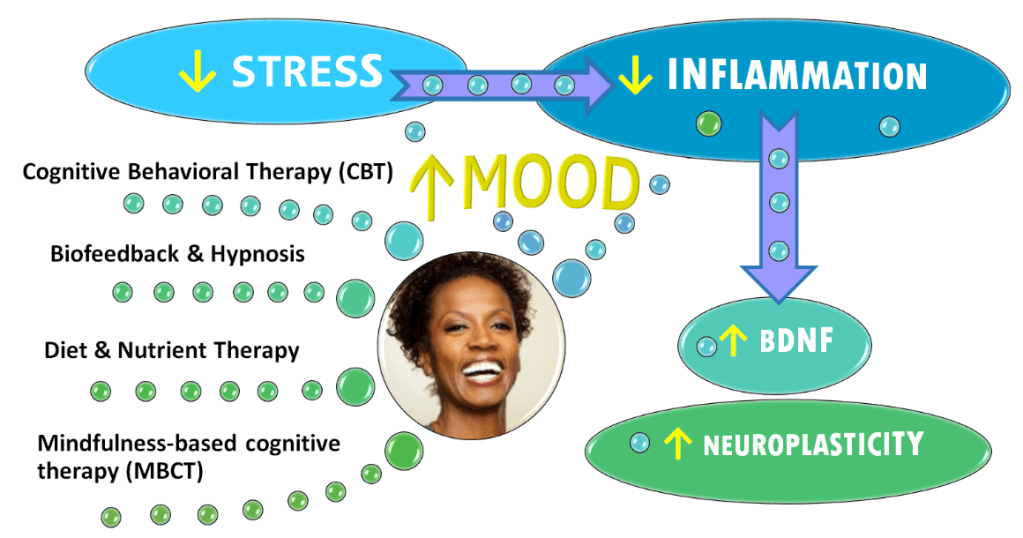

But you can stop inflammation before it wreaks havoc on your brain by treating stress. Biofeedback is an effective way to cut stress. 13, 14 And it is used to assist with relaxation therapy (RT), which is also effective for stress and anxiety management. 15

You can also stop inflammation through evidence-based changes to your diet and managing the health of your GI tract.

More good news is that experimental evidence shows reductions in BDNF can be reversed by long-term treatment of depression including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). 16 When one begins to recover from depression, BDNF returns to normal levels and the brain literally physically regenerates. 17, 18, 19, 20

Biofeedback-Assisted Relaxation Therapy (BART) is another way to help break the vicious cycle of anxiety and depression. Click link below:

For more on the many ways stress impacts the brain and ways we can recover, Click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

By using this website, you agree to accept MoodChangeMedicine.com website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- Capuco A., Urits I., Hasoon J., Chun R., Gerald B., Wang J. K., et al.. (2020). “Current perspectives on gut microbiota dysbiosis and depression.” Adv. Ther. 37, 1328–1346. 10.1007/s12325-020-01272-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021 ↩︎

- Robert M. Sapolsky. “Depression, antidepressants, and the shrinking hippocampus.” National Academy of Sciences. October 23, 2001 pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.231475998. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021 ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Makaracı Y, Makaracı M, Zorba E, Lautenbach F. “A Pilot Study of the Biofeedback Training to Reduce Salivary Cortisol Level and Improve Mental Health in Highly-Trained Female Athletes.” Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2023 Sep;48(3):357-367. doi: 10.1007/s10484-023-09589-z. Epub 2023 May 19. PMID: 37204539. ↩︎

- Ratanasiripong P, Park JF, Ratanasiripong N, Kathalae D. “Stress and anxiety management in nursing students: Biofeedback and mindfulness meditation.” J Nurs Educ. 2015;54(9):520-4. View abstract. ↩︎

- Kim HS, Kim EJ. “Effects of Relaxation Therapy on Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(2):278-284. View abstract. ↩︎

- Gomutbutra P, Yingchankul N, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn S, Srisurapanont M. “The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials.” Front Psychol. 2020 Sep 15;11:2209. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02209. PMID: 33041891; PMCID: PMC7522212. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Capuco A., Urits I., Hasoon J., Chun R., Gerald B., Wang J. K., et al.. (2020). “Current perspectives on gut microbiota dysbiosis and depression.” Adv. Ther. 37, 1328–1346. 10.1007/s12325-020-01272-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Meng F., Liu J., Dai J., Wu M., Wang W., Liu C., et al.. (2020). “Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in 5-HT neurons regulates susceptibility to depression-related behaviors induced by subchronic unpredictable stress.” J. Psychiatr. Res. 126, 55–66. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.05.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Zelada MI, Garrido V, Liberona A, Jones N, Zúñiga K, Silva H, Nieto RR. “Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) as a Predictor of Treatment Response in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): A Systematic Review.” Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 30;24(19):14810. doi: 10.3390/ijms241914810. PMID: 37834258; PMCID: PMC10572866. ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.