By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

April 24, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

The fervent search for the cause of depression and anxiety disorders has led researchers to stress-induced inflammation. 1

Scientists are attempting to discover why the benefits of talk therapies like CBT are comparable to that of medication in the short term but are more enduring than that of stand-alone treatment with antidepressants in the long term.

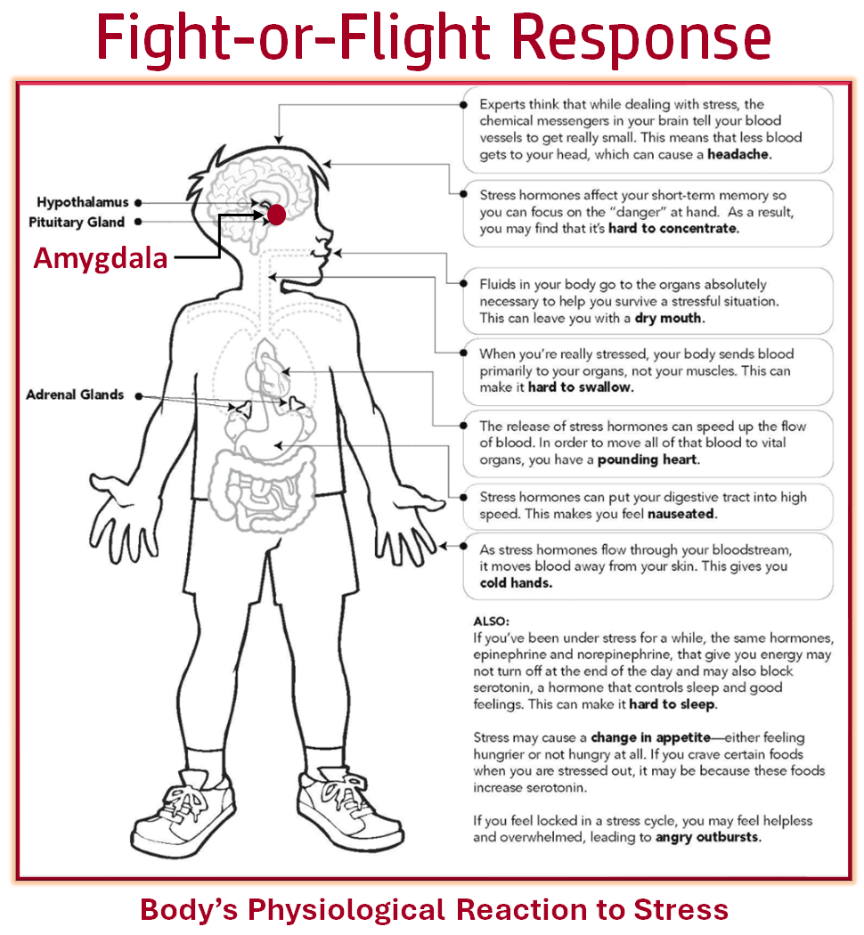

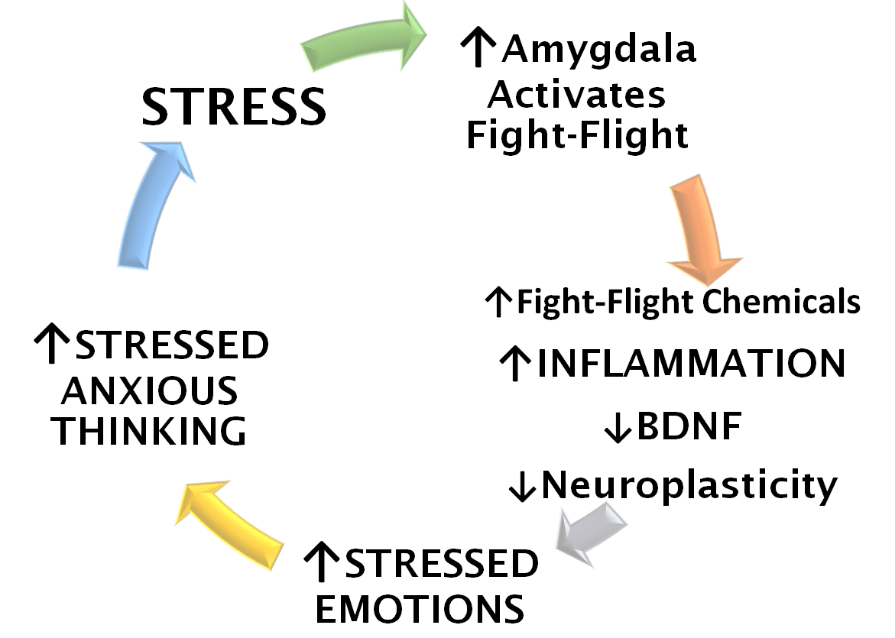

The answer lies in the brain and the stress that activates it. Stress kicks off a vicious cycle, activating a specialized area in the brain called the amygdala, which in turn floods the body with fight-or-flight stress-response chemicals.

Anxiety and depression are linked with a number of changes in brain activity like increased activation of the amygdala, a threat-center sentinel for the lightning-fast, subconscious recognition of potential threats. That’s where the fight-or-flight stress response is activated. Changes in how parts of the brain function during depressive episodes may account for the fatigue and changes in sleep, appetite and weight which are hallmarks of clinical depression. 2

Areas of the brain such as the amygdala are active in response to facing threats including significant emotional reactivity. But brain imaging and electrical scans are revealing that those same areas also show activity when we are in a depressed state. 3 This part of the brain is active in both anxiety and depression. 4

Brain-imaging studies appear to be consistent with the idea that depression emerges when parts of the brain that dampen the threat response are dysregulated. In these studies, CBT has been shown to normalize this dysregulation, calming the overactivation in the threat response regions of the brain in depressed patients. 5

Similar results from studies like these have been found for phobia. “Patients who were treated successfully with cognitive-behavioural therapy [CBT] showed normalization in the activity of [brain] structures that have been implicated in emotional reactivity.” 6

Researchers speculate that medications work more directly on the threat system including its sentinel—the amygdala—by chemically suppressing it, whereas cognitive therapy works on other brain areas that in turn help to dampen threat center overactivation. 7

Medications like antidepressants, also used to treat anxiety, are thought to suppress threat centers in the brain. When the medication that suppresses a threat center is discontinued, the brain is free to return to its previous overactivation pattern, which are seen in depression and anxiety. This difference may explain why when drugs are discontinued, the suppression of the threat center also ceases making future bouts of depression more likely in those who are treated with antidepressants and not those treated with cognitive therapy. It can also account for why the benefits of CBT are much more lasting as a result of talk therapy patients learning skills that dampen the threat center. 8

Some researchers assert that patients applying CBT “skills seem to result in the alteration of the patient’s general beliefs about themselves,” because they are less predisposed to a negative outlook, “a characteristic of depressed people and of people who are prone to depression.” 9 Negative outlook is also a driver of anxiety.

Anxious and depressive thinking colors the lens by which one views the stresses of life and amplifies them rather than ameliorating them.

Anxious and depressive thinking activates threat centers in the brain creating even more stress and inflammation. A vicious cycle of depressive and anxious thinking is triggered, amping up the fight-flight biology of stress, which in turn amps up depressed emotions and thinking.

Over time, no external stressors are required to fuel the vicious cycle because depression alone drives the cycle.

Using cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) skills for stress management gradually loosens the grip of the anxious and depressive thinking driving the vicious cycle. This, in turn, deactivates threat centers and shifts the body out of fight-flight mode, helping to relieve emotional stress.

Repeated practice of the CBT skills, when combined with the use of integrative stress-busting techniques like biofeedback, reinforce each other to turn a vicious cycle into a virtuous one.

Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to grow and to heal itself by creating new neurons and new connections between neurons, may also aid in the recovery from anxiety. A 2016 study of patients treated with cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder found that CBT improved neuroplasticity in the brain’s threat center that mediates anxiety, which researcher said explains a possible mechanism of how this proven anti-anxiety therapy works. 10

“Patients with anxiety disorders exhibit excessive neural reactivity in the amygdala, which can be normalized by effective treatment like cognitive behavior therapy (CBT),” the researchers concluded. 11

Scientists from the Laboratory of Fear and Anxiety Disorders explain that: “Neuroimaging studies have shown that amygdala activation in patients with anxiety disorders is significantly higher than that in controls in response to the same stimulus, which is decreased after effective cognitive behavioral therapy.” Patients with depression not only have higher levels of amygdala activation in response to emotional stimuli, but also have higher levels of amygdala activation all the time regardless of whether they are exposed to provocative stimuli or not, the scientists said. 12

CBT was found to reduce the size of the over-active amygdala, in the subjects with social anxiety. CBT was also found to reduce amygdala overactivation. The researchers postulated that the reduction in both the size and overactivation of the amygdala resulted in decreased reactivity to anxiety-provoking situations, which explains how CBT reduces social anxiety. 13

The ability of CBT to reduce the size of the amygdala is an example of the amazing neuroplasticity of the brain and the power of this talk therapy approach.

CBT is as effective for depression as antidepressant medication, a 2021 review of two randomized controlled studies confirms. 14 But newer data suggests that CBT is even more effective than antidepressants. 15

To learn more about how the efficacy of talk therapies like CBT compare to that of other treatments. Read more by clicking link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using this website, you agree to accept MoodChangeMedicine.com website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- Månsson KN, Salami A, Frick A, Carlbring P, Andersson G, Furmark T, Boraxbekk CJ. “Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder.” Transl Psychiatry. 2016 Feb 2;6(2):e727. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.218. PMID: 26836415; PMCID: PMC4872422. ↩︎

- Månsson KN, Salami A, Frick A, Carlbring P, Andersson G, Furmark T, Boraxbekk CJ. “Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder.” Transl Psychiatry. 2016 Feb 2;6(2):e727. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.218. PMID: 26836415; PMCID: PMC4872422. ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- Appelbaum, L.G., Shenasa, M.A., Stolz, L. et al. “Synaptic plasticity and mental health: methods, challenges and opportunities.” Neuropsychopharmacol. 48, 113–120 (2023). nature.com ↩︎

- Dams, Travis J. MD; Dhesi, Tajinder S. MD. “Is individual cognitive behavioral therapy as effective as antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder?.” Evidence-Based Practice. 24(5):p 21-22, May 2021. | DOI: 10.1097/EBP.0000000000001075 journals.lww ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.