By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)—A Talk Therapy Technique Shown to Be More Effective Than Antidepressants & Anti-Anxiety Drugs

April 24, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

“CBT is an effective, gold-standard treatment for anxiety and stress-related disorders,” according to authors from the Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry. “CBT uses specific techniques to target unhelpful thoughts, feelings and behaviors shown to generate and maintain anxiety. CBT can be used as a stand-alone treatment, may be combined with standard medications for the treatment of patients with anxiety disorders (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), or used with novel interventions (e.g., mindfulness).” 1

CBT is also first on a list of possible psychotherapeutic approaches to depression given by UpToDate, an evidence-based, clinical decision support database relied on by thousands of medical doctors and the biggest hospitals and clinics around the world. UpToDate endorses combining psychotherapy with medication. But it asserts that psychotherapy by itself works as well as medication.

“Despite being comparably effective, one advantage of psychotherapy is that some of its benefits often persist even after active treatment ends. Psychotherapy may help people develop new coping skills as well as more adaptive ways of thinking about life problems. The same is not necessarily true of antidepressants; many who take antidepressants alone relapse after stopping them”, according to UpToDate.

What is clear is that psychotherapy in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is as efficacious as antidepressant medication and that “its effects are more enduring.” 2

More recent research found CBT to be significantly more effective for improving depression than antidepressants. 3

A randomized, placebo-controlled study comparing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to antidepressant SSRI medication found that the two types of treatment have comparable effectiveness even in moderate to severe major depression. 4, 5 But CBT gains a distinct advantage over antidepressants over time researchers found.

After 16 weeks of having just cognitive behavioral therapy, its effectiveness for depression is nearly identical to that of people getting only pharmaceutical drugs. But when CBT and drugs are discontinued, the chances of depression returning are more than three times greater for people on drugs than for those getting CBT. For those taking antidepressants, there’s a 54% chance of relapse. It’s 17% for those getting CBT. 6, 7

Other types of talk therapy have also been shown to be effective for depression. A 2024 randomized clinical study found that behavioral activation therapy (BA) had identical efficacy to a variety of antidepressant medications in depressed patients with heart failure. 8

The most common antidepressant drugs got bottom-of-the barrel results in a landmark systematic review comparing the drugs’ effect on depression with that of the talk-therapy CBT and a range of exercise modalities, according to data published by the prestigious British Medical Journal in February 2024.

“We found some forms of exercise to have stronger effects than SSRIs alone,” wrote the researchers who conducted a meta-analysis of 218 studies with a total of 14, 170 depressed participants getting various treatments including antidepressants, CBT and exercise. 9

Data showed CBT and exercise to be considerably more effective than SSRIs. The effects were medium for cognitive behavioral therapy alone and small for SSRIs alone, comparable to what other meta-analyses have found for SSRIs. 10, 11 The researchers wrote: “Exercise may therefore be considered a viable alternative to drug treatment.”

The researchers called for a reappraisal of how depression patients are treated saying—in what can only be described as an understatement—that relegating exercise to the category of “complementary or alternative treatment” . . . “may be overly conservative. Instead, guidelines for depression ought to include prescriptions for exercise.” 12

For patients who prefer not to engage in psychotherapy such as CBT (cognitive behavior therapy), exercise may provide an alternative, said the researchers who noted that CBT was comparably effective to exercise. The researchers cautioned that the quality of the data for exercise was not as robust as for that of CBT.

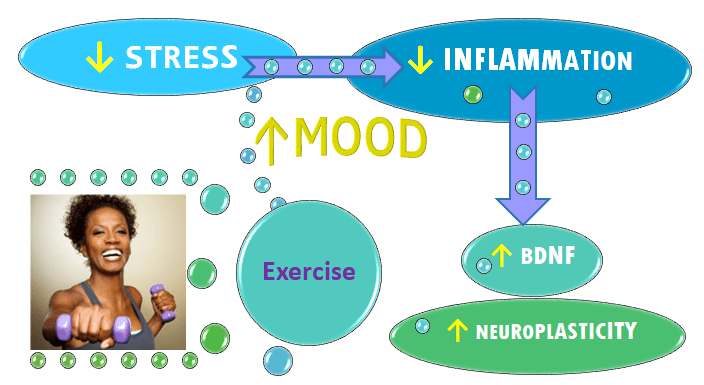

Exercise boosts mood and fights stress, which explains why it’s so helpful for overcoming anxiety and depression. It cuts inflammation, raises levels of a growth protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) which enhances neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to build new neurons and new connections. Elevated levels of inflammation impair neuroplasticity, both of which have been linked to anxiety and depression.

Stressful lives trigger inflammation, and inflammation feeds the vicious cycles of anxiety or depression. So it makes sense to cut stress to improve mood and calm anxiety. Exercise is often used to help manage stress. Relaxation therapy (RT) in concert with biofeedback also targets stress. A stressed mind is reflected by a stressed body, with spikes in breathing, heart rate and muscle tension. Biofeedback skills are extremely portable—no workout gear needed. Anytime we want to use these skills to release stress and tension, they are available.

Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback is a specific form of biofeedback that measures heart rate and helps people learn how to vary heart rate in a particular way that shifts them out of the fight-or-flight state. HRV is thought to be an indices of resilience and behavioral flexibility.

“Adding HRV biofeedback to psychotherapy can increase heart rate variability and augment treatment effects in various mental disorders,” according to a 2022 review of studies on HRV and its therapeutic modulation in the context of psychopharmacology as well as psychiatric and neurological disorders. 13

Read more about how biofeedback cuts stress and about its efficacy in the treatment of anxiety and depression by clicking link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Curtiss JE, Levine DS, Ander I, Baker AW. “Cognitive-Behavioral Treatments for Anxiety and Stress-Related Disorders. Focus.” Am Psychiatr Publ. 2021 Jun;19(2):184-189. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20200045. Epub 2021 Jun 17. PMID: 34690581 ; PMCID: PMC8475916. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. “Cognitive Therapy vs Medications in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Depression.” Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409–416. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409 ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. “Cognitive Therapy vs Medications in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Depression.” Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):409–416. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409 ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- IsHak WW, Hamilton MA, Korouri S, et al. “Comparative Effectiveness of Psychotherapy vs Antidepressants for Depression in Heart Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(1):e2352094. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.52094 ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al.“Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.” Lancet 2018;391:1357-66.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. pmid:29477251 PubMed Google Scholar ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- Siepmann M, Weidner K, Petrowski K, Siepmann T. “Heart Rate Variability: A Measure of Cardiovascular Health and Possible Therapeutic Target in Dysautonomic Mental and Neurological Disorders.” Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2022 Dec;47(4):273-287. doi: 10.1007/s10484-022-09572-0. Epub 2022 Nov 22. PMID: 36417141; PMCID: PMC9718704. ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.