By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

May 8, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

Depression, anxiety and insomnia go hand-in-hand.

People with anxiety often have trouble falling asleep, staying asleep and with tossing and turning. Depressed people can have these sleep problems but they can also have early morning awakening or sleep too much.

Insomnia may increase risk of developing depression tenfold, according to article in Hopkins Medicine. Other research suggests that up to 90% of people with major depression report sleep disturbances. 1

Insomnia triggers anxious feelings and is also a risk factor for the development of anxiety disorders. 2 Sixty to 70% of patients with generalized anxiety disorder report sleep problems. 3

But why do these frequently co-occurring mental health conditions—anxiety and depression—come with all these sleep problems?

Dysregulated hormones are a cause of the insomnia and disrupted sleep that comes with anxiety and depression.

Some researchers assert that the reduced levels of the sleep-hormone melatonin seen in depression are characteristic of the condition. 4

Though some small studies have found that melatonin supplements improve sleep in depressed patients, most of the research has not found benefits of melatonin supplementation in reducing depressive symptoms. 5, 6, 7

And using too much melatonin or taking it at the wrong time of day might make depression worse. 8, 9, 10, 11,12, 13

Melatonin supplements provide only marginal help for people with insomnia. It shortens the time it takes to fall asleep by just 7-12 minutes, according to an expert panel at NatMedPro. And it only increases total time asleep by about 8 minutes, pooled data from numerous studies show. 14, 15, 16

Melatonin also shifts the body out of the fight-flight mode in which stress levels are elevated and into a state in which we feel calm and relaxed. 17

That might lead one to believe melatonin can be taken to relieve anxiety. But it’s not known if melatonin would be of any help. Research on possible anti-anxiety properties of melatonin is still in its infancy. 18

The reason that supplementing a deficiency in melatonin doesn’t appear to improve depression is that the melatonin decline seen in depression is likely a consequence of other drivers of depression, not a cause.

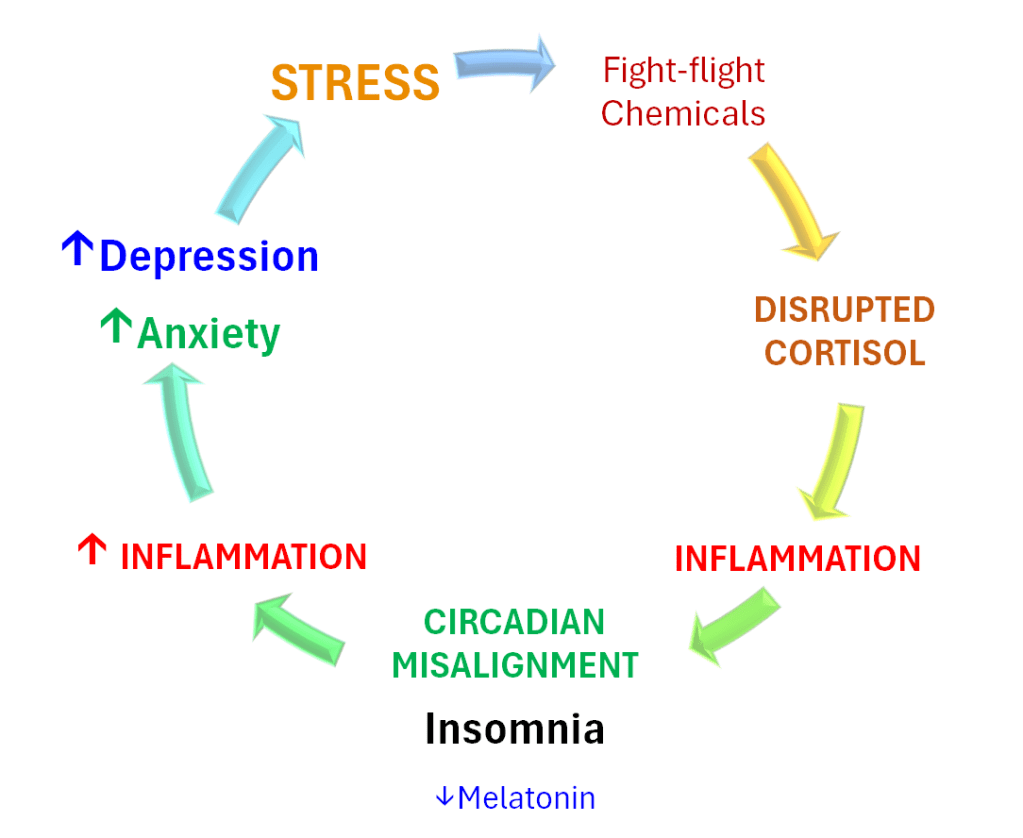

Insomnia and sleep disruption are downstream consequences of the drivers of depression and anxiety. Once sleep problems manifest, they feed a vicious cycle that amps up stress, anxiety and depression.

In depression, melatonin levels can drop, disrupting sleep. 19, 20, 21 In anxiety, activation of the stress response causes the release of stress hormones like cortisol and other neurochemicals that override the body’s sleep drive and cause anxious people loss of sleep.

Key brain networks in play for anxiety are also in play for depression, namely the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responsible for the fight-or-flight response to stress. Overactivation of the HPA axis leads to a vicious cycle that disrupts circadian rhythms, the body’s biological clocks. Trying to sleep with disrupted circadian rhythms is like trying to sleep with your alarm clock going off.

Stress is the common thread tying insomnia, circadian disruption, anxiety and depression together. Stress spikes the HPA axis. It ignites a firestorm of inflammation suppressing melatonin production in the pineal gland.

A pending divorce, missing a job deadline, or concerns about health—the kinds of things that generate daily stress—have a profound impact on brain biochemistry. This is the spark that ignites a vicious cycle.

The stress-fed vicious cycle that causes insomnia in anxious and depressed people takes off when chronic stress triggers repeated activation of the fight-or-flight response. This repeated activation of the HPA axis causes a cascade of biochemical events leading to increased inflammation that is strongly implicated in insomnia, depression, anxiety and a host of other conditions. 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32

Stress disrupts our body clock—our circadian rhythms. This disruption includes undesirable changes in the 24-hour cycles in cortisol and melatonin which cause disruptions in the body’s sleep clock. A disrupted sleep clock—resulting in too much, too little or fragmented sleep—can lead to depression and anxiety because circadian rhythms have a profound impact on mood.

Spikes in stress-induced cortisol and other fight-or-flight chemicals like adrenaline spur inflammatory substances in the brain and body. These inflammatory proteins shut down melatonin production in a brain structure called the pineal gland. 33, 34 Melatonin—like a conductor on a passenger train—keeps the body ticking on a 24-hour clock, our circadian rhythms. By suppressing melatonin, inflammation disrupts our circadian rhythms. Melatonin levels have been shown to decline in proportion to increases in measures of depressive symptom severity. 35, 36

The stress-hormone cortisol normally follows a circadian rhythm with levels peaking in the morning and declining throughout the day. In depression, there can be changes in the peak levels of cortisol. Some studies suggest an overall increase in cortisol production. 37 This alteration in cortisol can exacerbate the symptoms of depression.

A study found that depression severity was correlated with the amount of circadian misalignment: when your body’s internal clock is out of whack with the actual time of day. “The more delayed, the more severe the symptoms” 38 In anxiety, nighttime cortisol elevations put the body on alert, overriding the drive to sleep.

Circadian disturbances in the timing of the lowest point of body temperature in the 24-hour cycle, along with the disruptions to circadian rhythms of cortisol can respectively contribute to the characteristic symptoms of depression, such as early morning awakening and changes in the pattern of mood during the day. 39

The biological clock regulates changes in core body temperature, which normally are at their lowest in the morning. When we are depressed, we can reach the low temperature point too soon and we wake up too early. Combined with circadian disruptions in cortisol, it leaves us lying in bed mulling over problems.

This is why chronotherapy and light therapy—which employ carefully-timed exposure to light and small-doses of melatonin—is used to adjust the sleep-wake cycle and help restore normal circadian rhythms. This can be very helpful in the treatment of depression and anxiety. 40, 41

Chronic stress-induced spikes in cortisol not only trigger inflammation, they can also negatively impact mood and cause sleeplessness. Inflammation is a key driver which maintains the vicious cycle of insomnia and stressed mood.

The sleeplessness caused by stress-spiked cortisol and the resultant lowering of melatonin further exacerbates the inflammation that initially caused melatonin levels to drop in the first place. This perpetuates the vicious cycle.

Insomnia, even insufficient or inconsistent sleep, are all linked inflammation. 42, 43, 44 Insomnia, anxiety and depression can cause even more stress and inflammation. The vicious cycle continues to escalate as we lose more and more sleep and inflammation increases.

The evidence that inflammation plays an integral role in anxiety and depression is shown in many different studies.

For example, people with depression as well as people with anxiety each have higher levels of inflammation than people without either condition, research has found. 45, 46

Still other studies show that the higher the level of systemic inflammation in a depressed person, the more likely that their depression is severe, chronic and difficult to heal. 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52

When depressed people recover, not only does inflammation drop, but also melatonin levels return to pre-depression baseline levels. 53, 54

Researchers trying to account for the strong correlations between elevated inflammation, sleep problems and depression point to evidence that “sleep disturbance may increase inflammation, which in turn may contribute” to the onset or exacerbation of depression. 55 It is also possible that inconsistent or insufficient sleep may predispose sleep-deficient people to depression.

The complex interplay of sleep disturbances, inflammation, anxiety and depression is an emerging area of research and we don’t have all the answers yet. But, regardless of whether sleep problems drive the depression or whether the depression drives the sleep problems, evidence suggests a strong “influence of sleep disturbance on the onset, severity, and remission of depression.” 56 Maybe it’s a combination of both.

There are a number of ways that insomnia promotes inflammation. Sleep is the brain’s housecleaning system—the glymphatic system. It’s like a vacuum cleaner that’s turned on when we sleep, sucking up all the inflammatory debris.

In the deepest sleep phases, this “vacuum cleaner” picks up stuff like beta-amyloid protein linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Without a good night’s sleep, the clean-up is less thorough, allowing inflammatory debris to accumulate. Inflammation mounts and beta-amyloid builds up, impairing deeper, non-REM, slow-wave sleep. This damage makes it harder to sleep, further exacerbating the increased accumulation of inflammation. 57

Disrupted sleep might also cause inflammation through direct activation of the HPA axis, our fight-or-flight response to stress. 58 And inadequate sleep may also impair the body’s inflammation-fighting pathways. 59, 60

All these consequences of chronic insomnia may work simultaneously to spike inflammation, which can contribute to the development of heart disease, diabetes, stroke, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease. That’s why integrative treatment for insomnia also targets inflammation and stress—also key to healing co-occurring anxiety and depression.

Mood Change Medicine’s integrative treatment for insomnia in people with anxiety or depression is designed to break the vicious cycle of stress, inflammation and circadian disruption.

To find out how to break the vicious cycle, click links below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here

Citations

- Franzen P.L., Buysse D.J. “Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications.” Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2008;10(4):473–481. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/plfranzen. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. “Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression.” Sleep. 2007 Jul;30(7):873-80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.873. PMID: 17682658; PMCID: PMC1978360. ↩︎

- Carbone EA, Menculini G, de Filippis R, D’Angelo M, De Fazio P, Tortorella A, Steardo L Jr. “Sleep Disturbances in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The Role of Calcium Homeostasis Imbalance.” Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 1;20(5):4431. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054431. PMID: 36901441; PMCID: PMC10002427. ↩︎

- Sundberg I, Ramklint M, Stridsberg M, Papadopoulos FC, Ekselius L, Cunningham JL. “Salivary Melatonin in Relation to Depressive Symptom Severity in Young Adults.” PLoS One. 2016 Apr 4;11(4):e0152814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152814. PMID: 27042858; PMCID: PMC4820122. ↩︎

- Hansen MV, Danielsen AK, Hageman I, Rosenberg J, Gögenur I. “The therapeutic or prophylactic effect of exogenous melatonin against depression and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(11):1719-28. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dolberg OT, Hirschmann S, Grunhaus L. “Melatonin for the treatment of sleep disturbances in major depressive disorder.” Am J Psychiatr. 1998;155:1119-21. View abstract. ↩︎

- Serfaty, M. A., Osborne, D., Buszewicz, M. J., Blizard, R., and Raven, P. W. “A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of treatment as usual plus exogenous slow-release melatonin (6 mg) or placebo for sleep disturbance and depressed mood.” Int.Clin.Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(3):132-142. View abstract. ↩︎

- Carman J.S., Post R.M., Buswell R., Goodwin F.K. “Negative effects of melatonin on depression.” Am. J. Psychiatry. 1976;133:1181–1186. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.10.1181. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Buscemi, N., Vandermeer, B., Pandya, R., Hooton, N., Tjosvold, L., Hartling, L., Baker, G., Vohra, S., and Klassen, T. “Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders.” Evid. Rep.Technol.Assess.(Summ.) 2004;(108):1-7. View abstract. ↩︎

- Smits MG, van Stel HF, van der Heijden K, Meijer AM, Coenen AM, Kerkhof GA. “Melatonin improves health status and sleep in children with idiopathic chronic sleep-onset insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial.” J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1286–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- van der Heijden, K. B., Smits, M. G., van Someren, E. J., Ridderinkhof, K. R., and Gunning, W. B. “Effect of melatonin on sleep, behavior, and cognition in ADHD and chronic sleep-onset insomnia.” J Am Acad.Child Adolesc.Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):233-241. ↩︎

- van Geijlswijk, I. M., Korzilius, H. P., and Smits, M. G. “The use of exogenous melatonin in delayed sleep phase disorder: a meta-analysis.” Sleep. 2010;33(12):1605-1614. PubMed 21120122 ↩︎

- Petrie K, Dawson AG, Thompson L, Brook R. “A double-blind trial of melatonin as a treatment for jet lag in international cabin crew.” Biol Psychiatr. 1993;33:526-30. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Melatonin Monograph” NatMedPro Therapeutic Research Center database 3/8/2024. Monograph last modified on 3/7/2024, accessed April 2024. ↩︎

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Hooton N, et al. “The efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for primary sleep disorders. A meta-analysis.” J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1151-8. View abstract. ↩︎

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. “Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One 2013;8(5):e63773.” View abstract. ↩︎

- Pechanova, O., Paulis, L., Simko, F. “Peripheral and Central Effects of Melatonin on Blood Pressure Regulation” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15(10), 17920-17937;doi.org/10.3390/ijms151017920 ↩︎

- Repova K, Baka T, Krajcirovicova K, Stanko P, Aziriova S, Reiter RJ, Simko F. “Melatonin as a Potential Approach to Anxiety Treatment.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Dec 19;23(24):16187. doi: 10.3390/ijms232416187. PMID: 36555831; PMCID: PMC9788115. ↩︎

- Sundberg I, Ramklint M, Stridsberg M, Papadopoulos FC, Ekselius L, Cunningham JL. “Salivary Melatonin in Relation to Depressive Symptom Severity in Young Adults.” PLoS One. 2016 Apr 4;11(4):e0152814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152814. PMID: 27042858; PMCID: PMC4820122. ↩︎

- Souetre E, Salvati E, Belugou JL, Pringuey D, Candito M, Krebs B, et al. “Circadian rhythms in depression and recovery: evidence for blunted amplitude as the main chronobiological abnormality.” Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(3):263–78. Epub 1989/06/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- von Bahr C, Ursing C, Yasui N, et al. “Fluvoxamine but not citalopram increases serum melatonin in healthy subjects – an indication that cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 hydroxylate melatonin.” Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:123-7. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dzierzewski JM, Donovan EK, Kay DB, Sannes TS, Bradbrook KE. “Sleep Inconsistency and Markers of Inflammation.” Front Neurol. 2020 Sep 16;11:1042. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01042. PMID: 33041983; PMCID: PMC7525126. ↩︎

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. “Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation.” Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:40‐52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Irwin MR, Opp MR. “Sleep Health: Reciprocal Regulation of Sleep and Innate Immunity.” Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:129‐55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Irwin M.R. “Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health.” Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19(11):702–715. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0190-z. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, O’Neil A, et al. “So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from?” BMC Med. 2013 Sep 12;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-200. PMID: 24228900; PMCID: PMC3846682. ↩︎

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Papageorgiou C, Tsetsekou E, Soldatos C, Stefanadis C. “Anxiety in relation to inflammation and coagulation markers, among healthy adults: the ATTICA study.” Atherosclerosis. 2006 Apr;185(2):320-6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.001. Epub 2005 Jul 11. PMID: 16005881 ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- Lopresti AL. Cognitive behaviour therapy and inflammation: “A systematic review of its relationship and the potential implications for the treatment of depression.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;51(6):565-582. doi:10.1177/0004867417701996 ↩︎

- Hanson, J. A., & Huecker, M. R. (2022, September 9). “Sleep deprivation.” In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. NBK547676. ↩︎

- Walker WH 2nd, Walton JC, DeVries AC, Nelson RJ. “Circadian rhythm disruption and mental health.” Transl Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 23;10(1):28. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0694-0. PMID: 32066704; PMCID: PMC7026420. ↩︎

- Sundberg I, Ramklint M, Stridsberg M, Papadopoulos FC, Ekselius L, Cunningham JL. “Salivary Melatonin in Relation to Depressive Symptom Severity in Young Adults.” PLoS One. 2016 Apr 4;11(4):e0152814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152814. PMID: 27042858; PMCID: PMC4820122. ↩︎

- Souetre E, Salvati E, Belugou JL, Pringuey D, Candito M, Krebs B, et al. “Circadian rhythms in depression and recovery: evidence for blunted amplitude as the main chronobiological abnormality.” Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(3):263–78. Epub 1989/06/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Boyce, Philip, Barriball, Erin. “Circadian rhythms and depression.” Australian Family Physician. Vol. 39, Issue 5, May 2010. AFP. ↩︎

- Emens J, Lewy A, Kinzie JM, Arntz D, Rough J. “Circadian misalignment in major depressive disorder.” Psychiatry Res. 2009;168(3):259–61. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.009 . [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Boyce, Philip, Barriball, Erin. “Circadian rhythms and depression.” Australian Family Physician. Vol. 39, Issue 5, May 2010. AFP. ↩︎

- Dolberg OT, Hirschmann S, Grunhaus L. “Melatonin for the treatment of sleep disturbances in major depressive disorder.” Am J Psychiatr. 1998;155:1119-21. View abstract. ↩︎

- Fisher, Patrick M. et al. “Three-Week Bright-Light Intervention Has Dose-Related Effects on Threat-Related Corticolimbic Reactivity and Functional Coupling” Epub 2013 Dec 19. Biol Psychiatry. 2014 Aug 15;76(4):332-9. ↩︎

- Dzierzewski JM, Donovan EK, Kay DB, Sannes TS, Bradbrook KE. “Sleep Inconsistency and Markers of Inflammation.” Front Neurol. 2020 Sep 16;11:1042. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01042. PMID: 33041983; PMCID: PMC7525126. ↩︎

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. “Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation.” Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:40‐52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Irwin MR, Opp MR. “Sleep Health: Reciprocal Regulation of Sleep and Innate Immunity.” Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:129‐55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Raison CL, Miller AH. “Is depression an inflammatory disorder?” Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13:467–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Papageorgiou C, Tsetsekou E, Soldatos C, Stefanadis C. “Anxiety in relation to inflammation and coagulation markers, among healthy adults: the ATTICA study.” Atherosclerosis. 2006 Apr;185(2):320-6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.001. Epub 2005 Jul 11. PMID: 16005881 ↩︎

- S.R. Chamberlain, J. Cavanagh, P. de Boer, V. Mondelli, D.N. Jones, W.C. Drevets, et al.

“Treatment-resistant depression and peripheral C-reactive protein.” Br. J. Psychiatry. 2019. 214 (1) (2019), pp. 11-19 ↩︎ - Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Strawbridge R, Marwood L, King S, et al. “Inflammatory Proteins and Clinical Response to Psychological Therapy in Patients with Depression: An Exploratory Study.” J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 2;9(12):3918. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123918. PMID: 33276697; PMCID: PMC7761611. ↩︎

- M. Maes, E. Bosmans, R. De Jongh, G. Kenis, E. Vandoolaeghe, H. Neels. “Increased serum IL-6 and IL-1 receptor antagonist concentrations in major depression and treatment resistant depression.” Cytokine. 9 (11) (1997), pp. 853-858 ↩︎

- S.M. O’Brien, P. Scully, P. Fitzgerald, L.V. Scott, T.G. Dinan. “Plasma cytokine profiles in depressed patients who fail to respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy.” J. Psychiatric Res. 41 (3–4) (2007), pp. 326-331 ↩︎

- Lopresti AL. “Cognitive behaviour therapy and inflammation: A systematic review of its relationship and the potential implications for the treatment of depression.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;51(6):565-582. doi:10.1177/0004867417701996 ↩︎

- M. Maes, E. Bosmans, R. De Jongh, G. Kenis, E. Vandoolaeghe, H. Neels. “Increased serum IL-6 and IL-1 receptor antagonist concentrations in major depression and treatment resistant depression.” Cytokine. 9 (11) (1997), pp. 853-858 ↩︎

- S.M. O’Brien, P. Scully, P. Fitzgerald, L.V. Scott, T.G. Dinan. “Plasma cytokine profiles in depressed patients who fail to respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy.” J. Psychiatric Res. 41 (3–4) (2007), pp. 326-331 ↩︎

- Ballesio A. “Inflammatory hypotheses of sleep disturbance – depression link: Update and research agenda.” Brain Behav Immun Health. 2023 Jun 22;31:100647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100647. PMID: 37408788; PMCID: PMC10319168. ↩︎

- Ballesio A. “Inflammatory hypotheses of sleep disturbance – depression link: Update and research agenda.” Brain Behav Immun Health. 2023 Jun 22;31:100647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100647. PMID: 37408788; PMCID: PMC10319168. ↩︎

- Yan T., Qiu Y., Yu X., Yang L. “Glymphatic dysfunction: a bridge between sleep disturbance and mood disorders.” Front. Psychiatr. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.658340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Irwin M.R. “Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health.” Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19(11):702–715. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0190-z. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- He S., Chen X.X., Ge W., Yang S., et al. “Are anti-inflammatory cytokines associated with cognitive impairment in patients with insomnia comorbid with depression? A pilot study.” Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2021;13:989–1000. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S312272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Engert L.C., Dubourdeau M., Mullington J.M., Haack M. “0275 exposure to experimentally induced sleep disturbance affects the inflammatory resolution pathways in healthy humans.” Sleep. 2020;43:A104–A105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.