By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here

May 10, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

Billions of bacteria composed of some 40,000 bacterial species have evolved together with humans to live in our GI tract in an intricate ecosystem called the gut microbiota.Researchers from diverse fields of study have turned their attention to the gut-brain axis and how the microbiota affect mental health.

The gut-brain axis is a two-way biochemical conversation between our brains and bellies that plays a crucial role in our mental and physical health.

There’s burgeoning evidence that the balance of various bacterial species inhabiting our gut has an important influence on our psychological health via its effect on the gut-brain axis. 1

Changes in the composition of the microbes that colonize the GI tract have been implicated in triggering or maintaining depression and anxiety.2, 3, 4, 5 Some researchers unequivocally assert disturbances in the balance of gut bugs can cause depression and has a role in its cure. 6

Based on their antidepressant and anxiolytic effects, these beneficial bacteria that inhabit our GI tract have been dubbed “psychobiotics”.7 Someday doctors might routinely prescribe psychobiotics for their patients with anxiety and depression.

Certain types of gut bugs might promote depression. In a 2016 study titled “Transferring the Blues,” researchers transplanted gut bacteria obtained from patients with depression into the GI tracks of mice without pathogenic bacteria resulting in depressive-like behaviors in the mice that received the human gut-bug transplants. 8

Mice who received gut bugs transplanted from patients diagnosed with social anxiety disorder seemed to have caught the disorder from the humans. 9

The mice who got the gut-bug transplants exhibited heightened social fear responses.

Although the mice had normal behaviors with regard to depression and general anxiety-like behaviors, they showed heightened behaviors related to social fear. The researchers concluded that their experiment “posits the microbiota as a potential therapeutic target” for social anxiety disorder. 10

The evidence that the “microbiota-gut-brain axis” is a cause of depression is strong enough that it is a hot target for development of new antidepressants. 11

Many people can establish and maintain a healthy gut microbiota by consuming a diet with ample amounts of probiotic and prebiotic foods. In some cases, people might need probiotic supplements, particularly people who have had a lot of antibiotics.

Probiotics have a positive impact on alleviating stress responses, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and improving cognitive functions, human 12, 13, 14 and animal studies 15 have found.

Administration of the probiotic Bifidobacterium longum infantis to mice with chronic stress-induced depression “regulated emotional behavior” and increased levels brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a key brain chemical that boosts neuroplasticity by promoting the growth of new neurons and new connections between these cells. This probiotic also “significantly improved the scores in behavioral tests” and increased the level of the mood hormones 5-HTP and serotonin (5-HT) in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain. 16

There’s evidence that probiotics work against depression in humans. Patients who received probiotics had significantly improved symptoms of depression, a 2023 systematic review of 13 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 786 participants concluded. 17

Researchers analyzing data from 34 studies on the impact of prebiotics and probiotics on depression and anxiety concluded: “Probiotics yielded small but significant effects for depression and anxiety.” 18

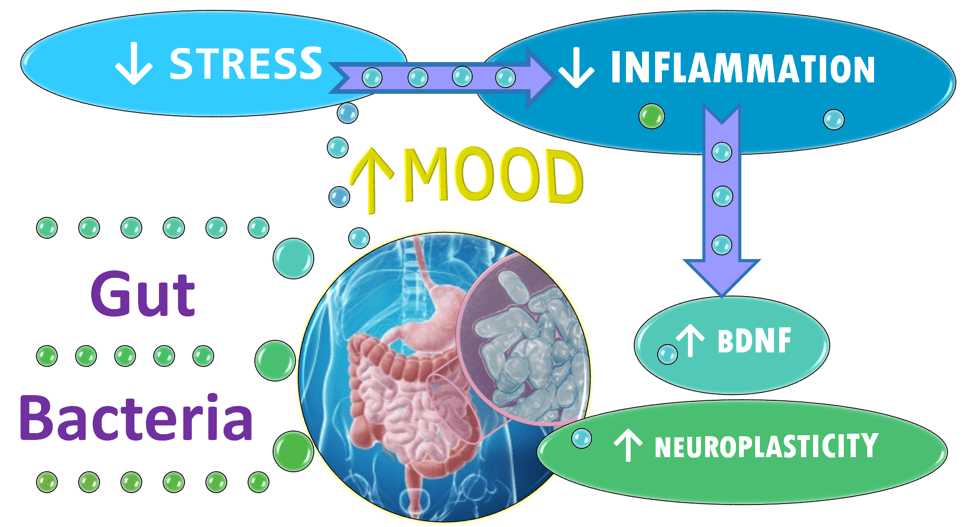

Researchers trying to discover the ways that the microbiota shape mental health are investigating its impact on the factors that are thought to kindle anxiety and depression including stress, inflammation and diminished neuroplasticity.

Changes in the balance of microbiota appear to affect a wide range of factors known to play a role in depression and anxiety. The microbiota regulates release of the mood-hormone serotonin and changes levels of systemic inflammation and of BDNF. It also impacts the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—the fight-or-flight machinery the body uses to respond to stress. 19, 20

Stress can trigger inflammation and mental disorders such as anxiety and depression. 21 Even stressed mice can show behaviors that are indicative of depression and anxiety and may respond to the same treatments that work to boost mood and restore a healthy microbiota in humans. 22

The gut microbiota plays a critical role in systemic inflammation. 23 Inflammation significantly decreases the levels of BDNF 24, 25 and reduces neuroplasticity. 26

Decreases in neuroplasticity and BDNF predict onset of depression. 27 Promoting the brain’s regenerative capacity via Increased levels of BDNF are associated with symptom improvements in depression.28, 29

In addition to supporting the health of the gut microbiota, our diets can also reverse inflammation and boost BDNF.

To find out what foods fuel well-being and what foods stoke anxiety and depression, click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here

Citations

- Martin CR, Osadchiy V, Kalani A, Mayer EA. “The brain-gut-microbiota axis.” Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6 (2) (2018), pp. 133-148 ↩︎

- Kelly JR, Borre Y, Ciaran OB, Patterson E, El Aidy S, Deane J, Kennedy PJ, Beers S, Scott K, Moloney G, et al. “Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat.” J Psychiatr Res. 82 (2016), pp. 109-118 ↩︎

- Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, Wang W, Tang W, Tan Z, Shi J, et al. “Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder.” Brain Behav Immun. 2015. 48 (2015), pp. 186-194 ↩︎

- Clarke G, Grenham S, Scully P, Fitzgerald P, Moloney RD, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “The microbiota-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner.” Mol Psychiatry. 2013. 18 (6) (2013), pp. 666-673 ↩︎

- Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Traplin A, O’Sullivan O, Crispie F, Moloney RD, Cotter PD, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “Gut microbiota depletion from early adolescence in mice: implications for brain and behaviour.” Brain Behav Immun. 2015. 48 (2015), pp. 165-173 ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023 Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910 ↩︎

- Cheng, L.-H., Liu, Y.-W., Wu, C.-C., Wang, S., & Tsai, Y.-C. “Psychobiotics in mental health, neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders.” Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, 27(3), 632–648. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2019.01.002 ↩︎

- Kelly J. R., Borre Y., O.’Brien C., Patterson E., El Aidy S., Deane J., et al.. (2016). “Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat.” J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016. 82, 109–118. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Ritz, Nathaniel L., Brocka, Marta Butler, Mary I. et al. “Social anxiety disorder-associated gut microbiota increases social fear.” PNAS Neuroscience. December 26, 2023 121 (1) e2308706120 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2308706120 ↩︎

- Ritz, Nathaniel L., Brocka, Marta Butler, Mary I. et al. “Social anxiety disorder-associated gut microbiota increases social fear.” PNAS Neuroscience. December 26, 2023 121 (1) e2308706120 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2308706120 ↩︎

- Chang L., Wei Y., Hashimoto K. “Brain-gut-microbiota axis in depression: a historical overview and future directions.” Brain Res. Bull. 2022. 182, 44–56. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.02.004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Akkasheh G., Kashani-Poor Z., Tajabadi-Ebrahimi M., Jafari P., Akbari H., Taghizadeh M., et al. “Clinical and Metabolic Response to Probiotic Administration in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Nutr. 2016. (Burbank Los Angeles County Calif.) 32, 315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.09.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Pinto-Sanchez M. I., Hall G. B., Ghajar K., Nardelli A., Bolino C., Lau J. T., et al. “Probiotic Bifidobacterium Longum NCC3001 Reduces Depression Scores and Alters Brain Activity: A Pilot Study in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome.” Gastroenterology. 2017. 153, 448–459.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Goh K. K., Liu Y. W., Kuo P. H., Chung Y. E., Lu M. L., Chen C. H. “Effect of Probiotics on Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis of Human Studies.” Psychiatry Res. 2019. 282, 112568. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112568 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Liu Q. F., Kim H. M., Lim S., Chung M. J., Lim C. Y., Koo B. S., et al. “Effect of Probiotic Administration on Gut Microbiota and Depressive Behaviors in Mice.” Daru J. Faculty Pharmacy Tehran Univ. Med. Sci. 2020. 28, 181–189. doi: 10.1007/s40199-020-00329-w [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Tian P, Zou R, Song L, Zhang X, Jiang B, Wang G, Lee YK, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W. “Ingestion of Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis strain CCFM687 regulated emotional behavior and the central BDNF pathway in chronic stress-induced depressive mice through reshaping the gut microbiota.” Food Funct. 2019. Nov 1;10(11):7588-7598. doi:10.1039/c9fo01630a. Epub 2019 Nov 5. PMID: 31687714. ↩︎

- Zhang, Q., Chen, B., Zhang, J. et al. “Effect of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics on depression: results from a meta-analysis.” BMC Psychiatry. 2023. 23, 477 (2023). doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04963-x BMC_psychiatry ↩︎

- Richard T. Liu, Rachel F.L. Walsh, Ana E. Sheehan. “Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2019. Vol. 102, 2019, Pages 13-23, ISSN 0149-7634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.023. (sciencedirect) ↩︎

- Du Y., Gao X.R., Peng L., Ge J.F. “Crosstalk between the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Depression.” Heliyon. 2020;6:e04097. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] quoted in pharmaceuticals-16-00565 ↩︎

- Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022. Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Al Bander Z, Nitert MD, Mousa A, Naderpoor N. “The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation: An Overview.” Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. Oct 19;17(20):7618. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207618. PMID: 33086688; PMCID: PMC7589951 ↩︎

- Sameer Hassamal. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1130989 ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID:PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Brunoni A, Lopes M, Fregni F. “A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression.” Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008 11(8):1169–80. 10.1017/S1461145708009309 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Sen S, Duman R, Sanacora G. “Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, Depression, and Antidepressant Medications: Meta-Analyses and Implications.” Biol Psychiatry. 2008 64(6):527–32. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.