By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

May 10, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

Researchers point to the strong association between the Western diet also known as Standard American Diet (SAD) and the risk for depression and anxiety. 1 This diet is typically low in vegetables, leafy greens, fruits, and legumes and high in packaged and ultra-processed foods.

Refined carbohydrates and starches like fries, chips, crackers and croissants; added sugars found in packaged cereals, cookies and pop tarts; high-fructose corn syrup sweetened snacks and sodas, artificially sweetened foods and beverages; refined fats, hydrogenated fats and white oils like margarine, canola, corn, safflower oils; high-fat dairy like cheese, butter and sweetened full-fat yogurt; fatty and highly processed meats like bacon, breakfast sausages, bologna, corn dogs, Salisberry steak and chicken nuggets; and comfort foods like pizza and macaroni and cheese typify the Standard American Diet (SAD).

Ultra-processed foods—loaded with additives like oil, fat, sugar, starch, and salt—are stripped of healthful nutrients. These foods are derived from components of plants or animal products or synthesized in laboratories. These are packaged foods with ingredients that are hard to pronounce and unrecognizable as food like acesulfame potassium, aspartame, neotame, sodium nitrite, benzoate, butylated hydroxytoluene and butylated hydroxyanisole and ever mysterious ingredients like “artificial flavors”.

The CBC explains “How Big Food keeps us eating through a combination of science and marketing” in their investigation of “Food cravings engineered by industry”.

People who consume high amounts of ultra-processed foods have an increased risk of anxiety, depression, obesity, different types of cancers and premature death, a 2024 study in the British Medical Journal found. 2

Eating a lot of ultra-processed food increases the chance of anxiety by 48%, of depression by 22% and of any mental disorder by 53%, the researchers found. Adverse impacts on sleep increase by 41% when consuming such a diet. 3

The researchers analyzed 59 prior analytic studies and pooled the data of all of them. Combining the data allowed these researchers to look at outcomes of consuming different amounts of ultra processed foods in 9, 888 ,373 study participants. 4

The enormous size of the study allows researchers to confidentially make sweeping conclusions about the impacts of eating ultra-processed food. “Taking the body of literature as a whole, there was consistent evidence that regularly eating higher – compared to lower – amounts of ultra-processed foods was linked to these adverse health outcomes,” said the study’s lead researchers in a NPR interview.

High-fat diets have been shown to result in increased inflammation and anxiety in laboratory mice. “Feeding on a chronic high-fat diet can promote anxiety-like behavior,” researchers at Laboratory of Fear and Anxiety Disorders said. When the mice were injected with an anti-inflammatory compound, the anxiety-like behavior disappeared. 5

Certain foods ignite inflammation in the body. Increased intake of processed, red, and organ meats; high-calorie beverages; and refined grains are strongly correlated to increases in blood markers of inflammation, an analysis of large health studies found. 6 In addition, highly-refined carbohydrates, sugars, trans-fats and saturated fats are also inflammation igniters.

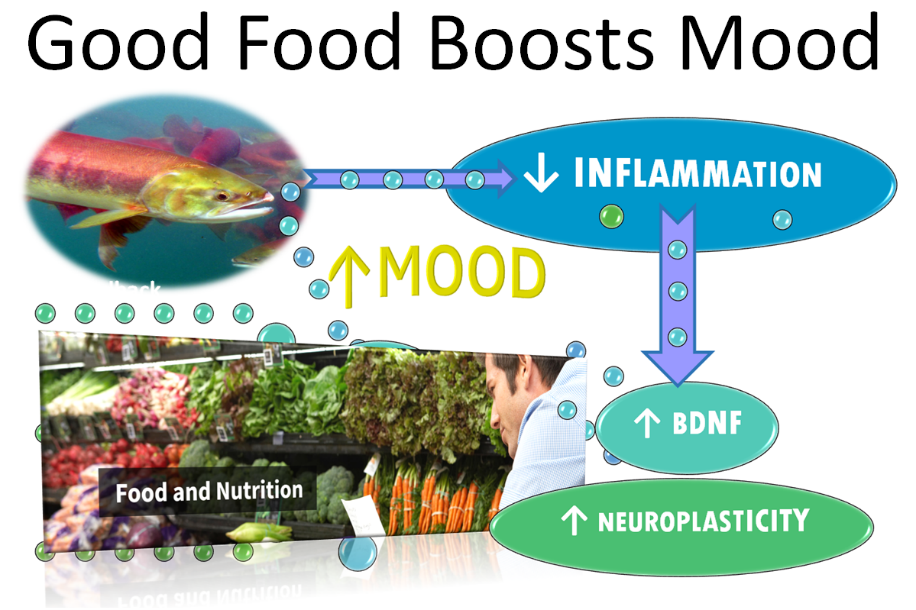

Inflammation taming foods include leafy greens and dark yellow vegetables such as carrots, yellow squash, yams; fruits like dark berries, acerola, and cherries; herbs and spices such as turmeric, ginger, garlic, and rosemary; herbal teas like chamomile, elderberry, hibiscus and green tea; oily fish and other omega-3 sources, including sardines, salmon, mackerel, herring, and fish oil; and legumes like lentils and beans.

The Mediterranean diet is an anti-inflammatory diet emphasizing olive oil, fruits, vegetables and fish that could lower the risk of anxiety and depression. 7, 8, 9, 10

Researchers found evidence that “dietary inflammatory potential is associated with the risk of depression and anxiety” by analyzing the data from 17 studies with a total of 157,409 participants. “The results of this 2022 study showed that individuals on pro-inflammatory diets were 45% more likely to suffer from depression and 66% more likely to suffer from anxiety disorders than those on anti-inflammatory diets. These results are in agreement with a number of previous studies.” 11

When the data was analyzed to isolate the impact solely on women, the news was even more stark. The increased risk of depression was 49% and 80% for anxiety. 12

Pro-inflammatory nutrients may activate the immune system and “that can lead to chronic low-grade inflammation,” the researchers averred. 13, 14, 15

“Diet and exercise have a profound impact on brain function,” said scientists cited in the 2022 study. “In particular, natural nutrients found in plants may influence neuronal survival and plasticity.” 16, 17

“In summary, the positive association between pro-inflammatory dietary style patterns with depression and anxiety found in this analysis can be useful in exploring strategies for the prevention and treatment of depression and anxiety.” 18

While there’s a lot of evidence in favor of eating a carefully-crafted diet with a range of anti-inflammatory foods and little or no pro-inflammatory ones, it might not be so easy for many people to design such a diet and stay on it. People can benefit from getting support from nutrition experts.

A 2017 randomized controlled trial of 67 depressed patients sought to answer the question: “If I improve my diet, will my mental health improve?” One half of them received nutrition counseling, and for them the answer was yes. Not true for the other half the patients who got social support sessions instead of nutrition counseling. 19

Those receiving expert nutrition counseling were encouraged to eat a modified version of the Mediterranean diet because it offered more flexible choices than a traditional, anti-inflammatory Mediterranean diet. The study diet emphasized vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, legumes, fruit, fish, poultry, lean red meat and unsalted nuts. It also encouraged “reducing intake of ‘extras’ foods, such as sweets, refined cereals, fried food, fast-food, processed meats and sugary drinks” among other dietary recommendations. 20

At the end of 12 weeks, 32.3% of the patients who got nutrition counseling achieved remission from moderate to severe depression while just 8.0% of the social support control group did. 21

“These results indicate that dietary improvement may provide an efficacious and accessible treatment strategy” for clinical depression, the researchers concluded. 22

The findings in favor of a scientifically-informed diet to treat depression are reinforced by a 2019 analysis of 16 randomized controlled studies, which assessed dietary interventions in clinical trials that included 45,826 participants with depressive symptoms. 23

There was a small, but statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms among those engaging in dietary interventions. 24

Why is it that an anti-inflammatory diet helps with anxiety and depression?

Inflammation has been implicated as an important part of the mechanism driving anxiety and depression. 25, 26, 27, 28 Hyperactivation of inflammatory proteins are linked to depression, anxiety and a host of other conditions. 29

Studies have also shown an association between inflammation and how our brains process emotional information. 30

Inflammation has numerous ways to interfere with the brain’s regenerative capacity—its neuroplasticity. Inflammation leaks in between brain neurons throwing a monkey wrench into the brain’s neural circuitry and at the same time inflammation significantly decreases neuroplasticity which could have helped to restore tissue damaged by inflammation. 31, 32

Neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to grow, reorganize and recover from stress-induced damage. It is the way that brain rewires neural networks so that it can perform in ways that differs from how it performed in the past.

Nutritional supplements that target taming inflammation can augment the benefits of an anti-inflammatory diet. Omega-3 fatty acids, usually consumed as fish oil, is under study to determine if it is effective for depression.

Depressed patients often have low levels of omega-3 fatty acids. 33

A number of studies shows that omega-3 fatty acid supplements are very effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder and other psychiatric disorders. But research is ongoing and not all studies have found benefits. High-dose EPA omega-3’s—a type of fish oil—also can reduce inflammation and may also improve depression. 34

So far, omega-3s have not proven effective as a stand-alone treatment for depression but, have shown efficacy when combined with other treatments.

Omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil was given the highest recommendation among nutritional treatments for unipolar depression based on a 2-year review of studies on natural medicines for major psychiatric disorders by a group of 31 leading academics and clinicians from 15 countries. But they declined to recommend fish oil as a stand-alone treatment. 35

Omega-3 fatty acid from fish oil is a powerful anti-inflammatory and also works synergistically with exercise to decrease inflammation 36, 37 and increase connectivity between brain cells. That’s got two-for-one benefits. Inflammation is broadly harmful to body. But it’s particularly harmful in the brain for mental health.

That’s because inflammation significantly decreases the levels of a key brain chemical called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) 38, 39 that boosts neuroplasticity by promoting the growth of new neurons and new connections between these cells. When BDNF goes down, so does neuroplasticity. 40 Decreases in neuroplasticity and BDNF predict onset of depression. 41

Promoting the brain’s regenerative capacity via increased levels of BDNF are associated with symptom improvements in depression. 42, 43

The concurrent effects of exercise along with a diet containing omega-3 (DHA), found in fish oil, involve BDNF’s effects on increasing connections between neurons in the brain. 44 But aerobic exercise alone has the power to boost BDNF levels and thereby stimulate the growth of new brain neurons. 45 And that’s not all that exercise can do for mental health by a long shot.

To read about the scientific study that found that exercise is far more effective than antidepressant medication, click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Mykletun A, Williams LJ, Hodge AM, O’Reilly SL, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Berk M. “Association of Western and Traditional Diets With Depression and Anxiety in Women.” Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167 (3):305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Lane M M, Gamage E, Du S, Ashtree D N, McGuinness A J, Gauci S et al. “Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses.” BMJ. 2024; 384 :e077310 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-077310 ↩︎

- Lane M M, Gamage E, Du S, Ashtree D N, McGuinness A J, Gauci S et al. “Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses.” BMJ. 2024; 384 :e077310 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-077310 ↩︎

- Lane M M, Gamage E, Du S, Ashtree D N, McGuinness A J, Gauci S et al. “Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses.” BMJ. 2024; 384 :e077310 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-077310 ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160 ↩︎

- Tabung FK, Smith-Warner SA, Chavarro JE, Wu K, Fuchs CS, Hu FB, Chan AT, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. “Development and Validation of an Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Index.” J Nutr. 2016 Aug;146(8):1560-70. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.228718. Epub 2016 Jun 29. PMID: 27358416; PMCID: PMC4958288. ↩︎

- Aucoin M, LaChance L, Naidoo U, Remy D, Shekdar T, Sayar N, et al. “Diet and Anxiety: A Scoping Review.” Nutrients. 2021 Dec 10;13(12):4418. doi: 10.3390/nu13124418. PMID: 34959972; PMCID: PMC8706568.f ↩︎

- Moufidath Adjibade, Cédric Lemogne, Mathilde Touvier, Serge Hercberg, et al. “The Inflammatory Potential of the Diet is Directly Associated with Incident Depressive Symptoms Among French Adults.” The Journal of Nutrition. 2019. Vol, 149, Issue 7, 2019, Pages 1198-1207. ↩︎

- Yin, W., Löf, M., Chen, R. et al. “Mediterranean diet and depression: a population-based cohort study.” Int J Behav Nutr Phys. 2021 Act 18, 153 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01227-3 biomedcentral ↩︎

- Bayes J, Schloss J, Sibbritt D. “The use of diet for preventing and treating depression in young men: current evidence and existing challenges.” British Journal of Nutrition. 2024;131(2):214-218. doi:10.1017/S000711452300168X cambridge.british-journal-of-nutrition ↩︎

- Li X, Chen M, Yao Z, Zhang T, Li Z. “Dietary inflammatory potential and the incidence of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis.” J Health Popul Nutr. 2022 May 28;41(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s41043-022-00303-z. PMID: 35643518; PMCID: PMC9148520. ↩︎

- Li X, Chen M, Yao Z, Zhang T, Li Z. “Dietary inflammatory potential and the incidence of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis.” J Health Popul Nutr. 2022 May 28;41(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s41043-022-00303-z. PMID: 35643518; PMCID: PMC9148520. ↩︎

- Bosma-den Boer MM, van Wetten ML, Pruimboom L. “Chronic inflammatory diseases are stimulated by current lifestyle: how diet, stress levels and medication prevent our body from recovering.” Nutr Metab. (Lond) 2012;9(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, et al. “Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(2):341–354. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Li X, Chen M, Yao Z, Zhang T, Li Z. “Dietary inflammatory potential and the incidence of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis.” J Health Popul Nutr. 2022 May 28;41(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s41043-022-00303-z. PMID: 35643518; PMCID: PMC9148520. ↩︎

- van Praag H, Lucero MJ, Yeo GW, et al. “Plant-derived flavanol (-)epicatechin enhances angiogenesis and retention of spatial memory in mice.” J Neurosci. 2007;27(22):5869–5878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0914-07.2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Li X, Chen M, Yao Z, Zhang T, Li Z. “Dietary inflammatory potential and the incidence of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis.” J Health Popul Nutr. 2022 May 28;41(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s41043-022-00303-z. PMID: 35643518; PMCID: PMC9148520. ↩︎

- Li X, Chen M, Yao Z, Zhang T, Li Z. “Dietary inflammatory potential and the incidence of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis.” J Health Popul Nutr. 2022 May 28;41(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s41043-022-00303-z. PMID: 35643518; PMCID: PMC9148520. ↩︎

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. “A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’trial).” BMC Med. 2017. 15:1–13. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. “A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’trial).” BMC Med. 2017. 15:1–13. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. “A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’trial).” BMC Med. 2017. 15:1–13. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. “A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’trial).” BMC Med. 2017. 15:1–13. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Firth J, Marx W, Dash S, et al. “The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Psychosom Med. 2019;81(3):265–280. PMC6455094 ↩︎

- Firth J, Marx W, Dash S, et al. “The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” Psychosom Med. 2019;81(3):265–280. PMC6455094 ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, O’Neil A, et al. “So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from?” BMC Med. 2013 Sep 12;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-200. PMID: 24228900; PMCID: PMC3846682 ↩︎

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Papageorgiou C, Tsetsekou E, Soldatos C, Stefanadis C. “Anxiety in relation to inflammation and coagulation markers, among healthy adults: the ATTICA study.” Atherosclerosis. 2006 Apr;185(2):320-6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.001. Epub 2005 Jul 11. PMID: 16005881 ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Maydych V. “The Interplay Between Stress, Inflammation, and Emotional Attention: Relevance for Depression.” Front Neurosci. 2019 Apr 24;13:384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00384. PMID: 31068783; PMCID: PMC6491771. ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021 ↩︎

- Suneson, K., Ängeby, F., Lindahl, J. et al. “Efficacy of eicosapentaenoic acid in inflammatory depression: study protocol for a match-mismatch trial.” BMC Psychiatry. 2022. 22, 801. doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04430-z ↩︎

- Wani AL, Bhat SA, Ara A. “Omega-3 fatty acids and the treatment of depression: a review of scientific evidence.” Integr Med Res. 2015 Sep;4(3):132-141. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2015.07.003. Epub 2015 Jul 15. PMID: 28664119; PMCID: PMC5481805. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23:424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- Wani AL, Bhat SA, Ara A. “Omega-3 fatty acids and the treatment of depression: a review of scientific evidence.” Integr Med Res. 2015 Sep;4(3):132-141. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2015.07.003. Epub 2015 Jul 15. PMID: 28664119; PMCID: PMC5481805. ↩︎

- Stoyan Dimitrov, Elaine Hulteng, and Suzi Hong. “Inflammation and exercise: Inhibition of monocytic intracellular TNF production by acute exercise via β2-adrenergic activation” by in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. Published online December 21 2016 doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.017 pubmed 28011264 ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021 ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Brunoni A, Lopes M, Fregni F. “A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression.” Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008 11(8):1169–80. 10.1017/S1461145708009309 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Sen S, Duman R, Sanacora G. “Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, Depression, and Antidepressant Medications: Meta-Analyses and Implications.” Biol Psychiatry. 2008 64(6):527–32. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. “Docosahexaenoic acid dietary supplementation enhances the effects of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition.” Neuroscience. 2008;155:751–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Knaepen K, Goekint M, Heyman EM, Meeusen R. “Neuroplasticity – exercise-induced response of peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a systematic review of experimental studies in human subjects.” Sports Med. 2010. Sep 1;40(9):765-801. PMID: 20726622. 2010;40:765–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.