By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

May 14, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

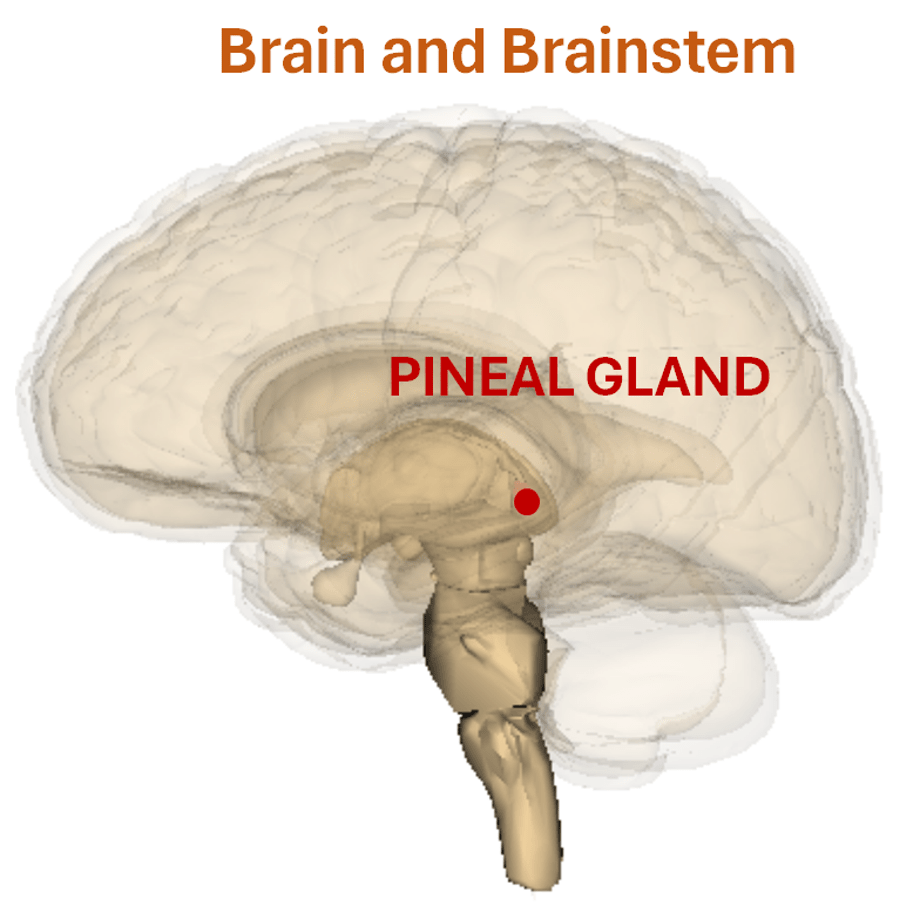

Melatonin is a sleep-promoting hormone that is naturally produced and secreted by the pineal gland in the brain. The impact of naturally-occurring melatonin on our bodies is broad, profound, and not completely understood.

It affects many basic body systems beyond sleep and circadian rhythms including levels of stress hormones like cortisol, growth hormone, and sex hormones among others. 1, 2, 3

Natural levels of melatonin produced by the body have a strong impact on sleep. In general, the sleep promoting effects of retail melatonin supplements appear to be modest for most people. Supplementation may be more helpful for some people than for others.

People with a condition known as delayed sleep phase syndrome, colloquially called “night owls,” can benefit more from taking melatonin supplements than most people with insomnia. It can also be helpful for jet lag and may be more helpful in people with reduced natural levels of melatonin.

Links to more information on melatonin:

Getting morning sunlight—which acts on your body’s natural melatonin levels–has a dramatically stronger impact on your sleep than taking melatonin supplements. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

And when compared to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), melatonin supplementation has a much smaller effect on sleep. CBT-I is the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s gold standard for treating insomnia and is frequently coupled with light therapy. Melatonin may be a helpful adjunct to CBT-I, depending on the individual.

Specific nutrients are required by the body to convert dietary precursors in food into melatonin. Diet plays a role in optimizing natural melatonin levels.

Melatonin Regulates the Sleep Clock

Melatonin’s core function is as a “chronobiotic” to synchronize our biological rhythms. Melatonin sends signals throughout the body saying it is time to switch to nighttime physiology, also described as “biological night.” It also sets the length of the biological day by signaling body systems involved in daytime physiology to power up.

Based on seasonal changes in light levels, melatonin shifts our circadian clock, including the timing of sleep, daily changes in core body temperature and cortisol levels, a stress hormone elevated in anxious and depressive states.

Melatonin existed before humans evolved. All species—even bacteria and plants—are believed to secrete melatonin. Its production in humans is tied to the time of day based on current levels of daytime light.

After the daytime sun has faded, melatonin production ramps up, inducing drowsiness and lowering body temperature. As natural melatonin levels climb, we get progressively sleepier.

Melatonin production in the brain peaks in middle of night, declines and is minimal during day.

Natural Melatonin: The Super Hormone

In addition to its sleep-regulating role, melatonin produced by the body supports health and well-being by acting as a free-radical scavenger via its antioxidant effects, which may slow aging, some animal and test-tube studies suggest. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

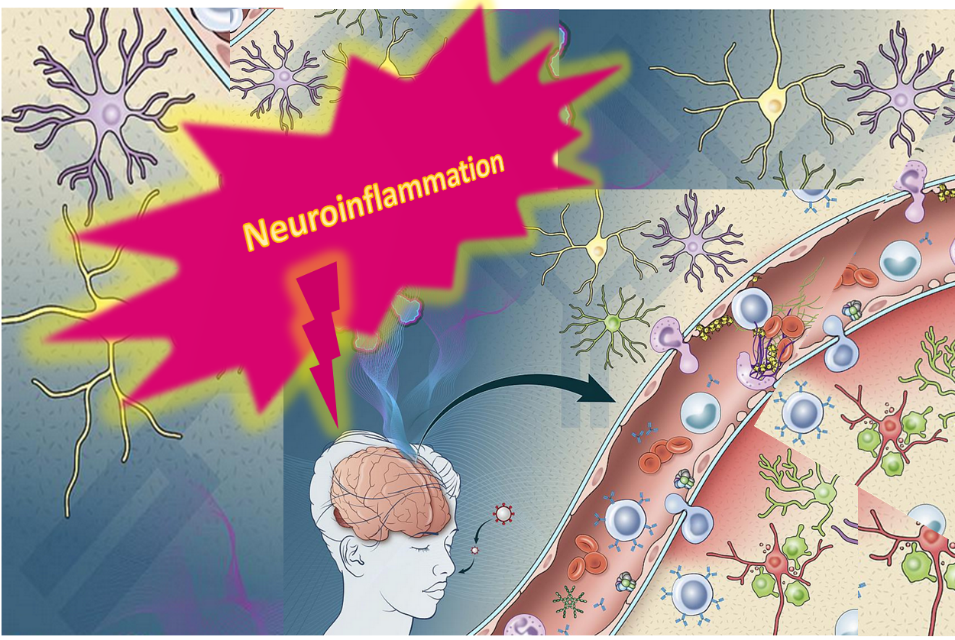

Melatonin naturally produced in the body has neuroprotective affects in the brain. 20 Melatonin produced in the body prevents damage to the nervous system and brain not only by intercepting free radicals before they cause damage, but also by reducing inflammation. 21

Anxiety and depression set off inflammation in the brain and throughout the body. Inflammation has been implicated as an important part of the mechanism driving anxiety and depression. 22, 23, 24, 25

Stress is a trigger of both inflammation and mental disorders such as anxiety and depression. 26

Melatonin also shifts the body out of the sympathetic state—the fight-flight mode in which stress levels increase—into a parasympathetic state, the rest and repair mode in which we feel calm and relaxed. 27

This may be part of the reason why getting a good night of sleep is so crucial for our mental and physical health.

Light Regulates Melatonin

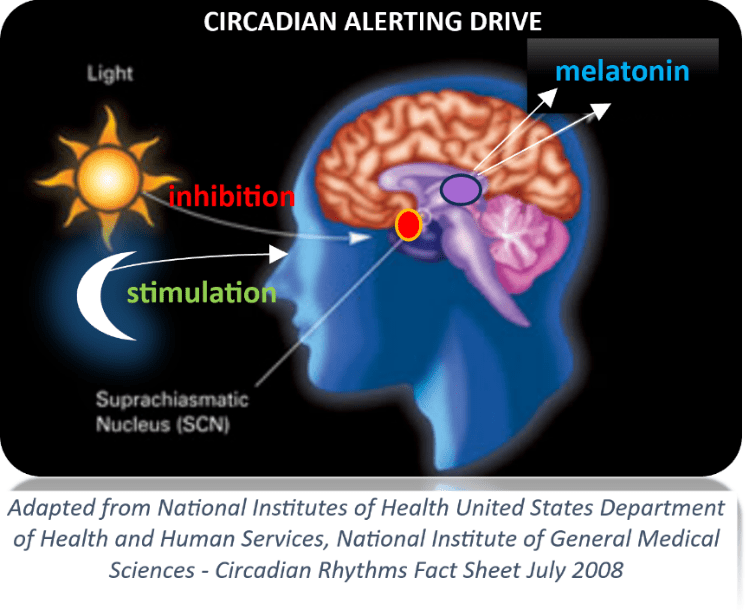

Light levels, as well as the color of the light hitting our eyes, control melatonin levels via a brain structure known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The SCN directs the pineal gland to either shut down or ramp up melatonin production depending on the type of light hitting the eyes.

Light from the morning sun is in the blue end of the spectrum. Blue light shuts down melatonin production in the morning allowing us become alert after a night’s sleep. The brighter the blue light, the more strongly it inhibits melatonin. This may be why it sometimes seems easier to get out of bed on a bright sunny day rather than a dark, overcast one.

In addition to changes in the light level, the color of light also influences melatonin levels and sleepiness. Whereas blue light shuts down melatonin, red light—like that of the setting sun—stimulates melatonin production. At dusk, when there’s less bright blue light and more dim red light hitting our eyes, melatonin levels rise and we feel sleepy facilitating falling asleep at night.

Light therapy, is a way of using the light hitting our eyes to help regulate the circadian sleep clock. Light therapy is frequently incorporated into cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) treatment programs. In such CBT-I programs, patients learn how to use light from the sun or from a special light box to obtain blue light at optimal times. They also learn ways to avoid blue light as bedtime approaches.

Certain types of light exposure improve communication among parts of the brain that trigger the stress response and those responsible for reasoning and for shutting down the stress response. 28

Light therapy is a helpful treatment for either depression, insomnia, or both. Perhaps it’s due to direct effects of light on the brain or due to light’s role in regulating melatonin and helping people get better sleep. 29, 30, 31, 32, 33

Light therapy was associated with improvements in total sleep time, sleep onset, sleep quality, fatigue, and other symptom, according to a systematic review of 53 clinical studies with a total of 1154 participants with insomnia. 34 And there is evidence that light therapy may also be helpful for anxiety. 35

Do Melatonin Supplements Act Like the Natural Hormone?

Most people take melatonin that is sold as an over-the-counter sleep aid in pharmacies, supplement stores or by online vitamin sellers. People getting treatment for delayed sleep phase syndrome (night owls) or jet lag take melatonin for its chronobiotic ability to shift the circadian clock.

Some experts cite evidence that both lower and higher doses of melatonin supplements may reinforce natural circadian rhythms of melatonin release. 36 But higher doses of supplements may not mimic natural rhythms of melatonin release.

While doses at the low end of the range may mimic the natural pattern, taking melatonin supplements at typical doses to cause sleepiness does not appear to replicate the body’s natural physiologic release of melatonin. 37, 38, 39

The peak levels of melatonin from supplementation can be as much 350-10,000 times higher than normal nighttime melatonin levels. 40, 41, 42

How Melatonin Acts in The Body: Dose and Timing Matter

How melatonin supplements act in the body depends on when and how much is taken.

Melatonin signals the body to shift the timing of daily biological cycles, including surges and drops in core body temperature, the pattern of release of cortisol, as well as when sleepiness occurs. 43, 44, ,45

Taking doses that are smaller and closer to those that are naturally occurring in the body, timed around “dim-light melatonin onset” (DLMO) will shift the phase of the human circadian clock. DLMO is defined as the start of melatonin production in the evening during dim light conditions. 46 This is helpful for night owls who need to fall asleep faster in order to wake up earlier to match demands of career, school and family.

Melatonin taken 20 to 30 minutes before sleep in typical doses can make it easier to fall asleep and some people report small improvements in sleep quality. 47, 48, 49, 50

Optimal dosing of melatonin hasn’t been established. 51

Since the extent to which melatonin from supplements is available for use by the body—called bioavailability—varies so widely, establishing an optimal dose may not be possible. The bioavailability ranges between 3% to 76% depending on the manufacturer and the biology of the consumer. 52, 53

Optimal dosing also depends on the goal of supplementation. For example, dosing regimens for shifting the circadian clock are different than for those inducing sleepiness. The typical dosing range is from 0.1 mg up to 8 mg, but for most supplements the dosing is 1 to 5 mg. Typical dosages in commercially available supplements lead to blood levels of melatonin that are 10-100 times higher than that of our maximum level of melatonin naturally occurring in the body at night. 54, 55

Depending on the time of day taken, the smallest of commercially available doses (100-300 mcg or 0.1 to 0.3 mg) lead to peak nighttime blood levels of melatonin that are closer to those that are naturally occurring in our bodies when it is at its maximum nighttime level. 56, 57

Melatonin supplements are sold in different formulations such as immediate and prolonged release. Few companies offer the ultra-low dose formulations used to shift the circadian clock.

Different formulations maintain raised melatonin levels over different durations. A 2 mg dose of a prolonged-release melatonin formulation led to melatonin levels in the normal range for 5-7 hours, a study found. 58 Another prolonged-release formulation led to above normal levels of melatonin for at least 8.5 hours. 59

Most companies say to take melatonin before bedtime. If the dose is taken at noon the time delay before it has its maximal effect can be as much as 220 minutes. If taken at 9 p.m. the time to reach maximum effects can be up to 60 minutes. 60

Sometimes the effects of melatonin can linger for 10 hours or more, even into the next day, creating sleepiness thorough the night and into daylight hours. 61, 62, 63

Dosing, timing, duration of treatment as well as the specific formulation of the products are different for different sleep problems and for different populations.

Always consult a physician or qualified healthcare professional before taking any supplements or medications.

To learn more about how effective melatonin supplements are for sleep problems, click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using this website, you agree to accept MoodChangeMedicine.com website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Brivio, F., Fumagalli, L., Fumagalli, G., Pescia, S., Brivio, R., DI, Fede G., et al. “Synchronization of cortisol circadian rhythm by the pineal hormone melatonin in untreatable metastatic solid tumor patients and its possible prognostic significance on tumor progression.” In Vivo. 2010;24(2):239-241. View abstract. ↩︎

- Meeking DR, Wallace JD, Cuneo RC, et al. “Exercise-induced GH secretion is enhanced by the oral ingestion of melatonin in healthy adult male subjects.” Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;141:22-6. View abstract. ↩︎

- Voordouw BC, Euser R, Verdonk RE, et al. “Melatonin and melatonin-progestin combinations alter pituitary-ovarian function in women and can inhibit ovulation.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:108-17. View abstract. ↩︎

- Lewy AJ, Ahmed S, Jackson JM, Sack RL. “Melatonin shifts human circadian rhythms according to a phase-response curve.” Chronobiol Int. 1992;9:380-92. View abstract. ↩︎

- Zaidan, R., Geoffriau, M., Brun, J., Taillard, J., Bureau, C., et al. “Melatonin is able to influence its secretion in humans: description of a phase-response curve.” Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60(1):105-112. View abstract. ↩︎

- Deacon, S. and Arendt, J. “Melatonin-induced temperature suppression and its acute phase-shifting effects correlate in a dose-dependent manner in humans.” Brain Res. 1995. 8-7-1995;688(1-2):77-85. View abstract. ↩︎

- Steinlechner, S. Melatonin as a chronobiotic: “PROS and CONS.” Acta Neurobiol.Exp (Warsz.) 1996;56(1):363-372. View abstract. ↩︎

- Lewy, A. J. and Sack, R. L. “Exogenous melatonin’s phase-shifting effects on the endogenous melatonin profile in sighted humans: a brief review and critique of the literature.” J Biol Rhythms. 1997;12(6):588-594. View abstract. ↩︎

- Cagnacci, A., Soldani, R., and Yen, S. S. “Contemporaneous melatonin administration modifies the circadian response to nocturnal bright light stimuli.” Am J Physiol. 1997;272(2 Pt 2):R482-R486. View abstract. ↩︎

- Hatonen, T., Alila, A., and Laakso, M. L. “Exogenous melatonin fails to counteract the light-induced phase delay of human melatonin rhythm.” Brain Res. 1996. 2-26-1996;710(1-2):125-130. View abstract. ↩︎

- Caballero, B., Vega-Naredo, I., Sierra, V., Huidobro-Fernandez, C., Soria-Valles,et al. “A. Melatonin alters cell death processes in response to age-related oxidative stress in the brain of senescence-accelerated mice.” J.Pineal Res. 2009;46(1):106-114. View abstract. ↩︎

- Carretero, M., Escames, G., Lopez, L. C., Venegas, C., Dayoub, J. C., Garcia, L., and Acuna-Castroviejo, D. “Long-term melatonin administration protects brain mitochondria from aging.” J.Pineal Res. 2009;47(2):192-200. View abstract. ↩︎

- Garcia, J. J., Pinol-Ripoll, G., Martinez-Ballarin, E., Fuentes-Broto, L., Miana-Mena, F. J., Venegas, C., Caballero, B., et al. “Melatonin reduces membrane rigidity and oxidative damage in the brain of SAMP8 mice.” Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32(11):2045-2054. View abstract. ↩︎

- Jagota, A. and Kalyani, D. “Effect of melatonin on age induced changes in daily serotonin rhythms in suprachiasmatic nucleus of male Wistar rat.” Biogerontology. 2010;11(3):299-308. View abstract. ↩︎

- Jung-Hynes, B. and Ahmad, N. ‘SIRT1 controls circadian clock circuitry and promotes cell survival: a connection with age-related neoplasms.” FASEB J. 2009;23(9):2803-2809. View abstract. ↩︎

- Magnanou, E., Attia, J., Fons, R., Boeuf, G., and Falcon, J. “The timing of the shrew: continuous melatonin treatment maintains youthful rhythmic activity in aging Crocidura russula.” PLoS.One. 2009;4(6):e5904. View abstract. ↩︎

- Paredes, S. D., Bejarano, I., Terron, M. P., Barriga, C., Reiter, R. J., and Rodriguez, A. B. “Melatonin and tryptophan counteract lipid peroxidation and modulate superoxide dismutase activity in ringdove heterophils in vivo. Effect of antigen-induced activation and age.” Age (Dordr.) 2009;31(3):179-188. View abstract. ↩︎

- Fukai, S. and Akishita, M. “Hormone replacement therapy—growth hormone, melatonin, DHEA and sex hormones.” Nihon Rinsho. 2009;67(7):1396-1401. View abstract. ↩︎

- Reiter, R. J., Paredes, S. D., Manchester, L. C., and Tan, D. X. “Reducing oxidative/nitrosative stress: a newly-discovered genre for melatonin.” Crit Rev.Biochem.Mol.Biol. 2009;44(4):175-200. View abstract. ↩︎

- Chen CQ, Fichna J, Bashashati M, Li YY, Storr M. “Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut.” World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep 14;17(34):3888-98. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i34.3888. PMID: 22025877; PMCID: PMC3198018. ↩︎

- Pechanova, O., Paulis, L., Simko, F. “Peripheral and Central Effects of Melatonin on Blood Pressure Regulation” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15(10), 17920-17937;doi.org/10.3390/ijms151017920 ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, O’Neil A, et al. “So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from?” BMC Med. 2013 Sep 12;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-200. PMID: 24228900; PMCID: PMC3846682. ↩︎

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Papageorgiou C, Tsetsekou E, Soldatos C, Stefanadis C. “Anxiety in relation to inflammation and coagulation markers, among healthy adults: the ATTICA study.” Atherosclerosis. 2006 Apr;185(2):320-6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.001. Epub 2005 Jul 11. PMID: 16005881 ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Pechanova, O., Paulis, L., Simko, F. “Peripheral and Central Effects of Melatonin on Blood Pressure Regulation” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15(10), 17920-17937;doi.org/10.3390/ijms151017920 ↩︎

- Fisher, Patrick M. et al. “Three-Week Bright-Light Intervention Has Dose-Related Effects on Threat-Related Corticolimbic Reactivity and Functional Coupling” Epub 2013 Dec 19. Biol Psychiatry. 2014 Aug 15;76(4):332-9. ↩︎

- Al-Karawi D, Jubair L. “Bright light therapy for nonseasonal depression: Meta-analysis of clinical trials.” J Affect Disord. 2016;198:64-71. View abstract. ↩︎

- Tuunainen, A., Kripke, D. F., and Endo, T. “Light therapy for non-seasonal depression.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2):CD004050. View abstract. ↩︎

- Golden, R. N., Gaynes, B. N., Ekstrom, R. D., Hamer, R. M., Jacobsen, F. M., Suppes, T., Wisner, K. L., and Nemeroff, C. B. “The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence.” Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):656-662. View abstract. ↩︎

- Lee TM, Chan CC. “Dose-response relationship of phototherapy for seasonal affective disorder: a meta-analysis.” Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999 May;99(5):315-23. PMID: 10353446. View abstract. ↩︎

- van Maanen A, Meijer AM, van der Heijden KB, Oort FJ. “The effects of light therapy on sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:52-62. View abstract. ↩︎

- van Maanen A, Meijer AM, van der Heijden KB, Oort FJ. “The effects of light therapy on sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:52-62. View abstract. ↩︎

- Fisher, Patrick M. et al. “Three-Week Bright-Light Intervention Has Dose-Related Effects on Threat-Related Corticolimbic Reactivity and Functional Coupling” Epub 2013 Dec 19. Biol Psychiatry. 2014 Aug 15;76(4):332-9. ↩︎

- Auld, F. et al. “Evidence for the efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of primary adult sleep disorders.” Sleep Med Rev. 2017; 34:10-22 DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.06.005 ↩︎

- Hahm, H., Kujawa, J., and Augsburger, L. “Comparison of melatonin products against USP’s nutritional supplements standards and other criteria.” J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash.) 1999;39(1):27-31. View abstract. ↩︎

- Grima NA, Rajaratnam SMW, Mansfield D, Sletten TL, Spitz G, Ponsford JL. “Efficacy of melatonin for sleep disturbance following traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled trial.” BMC Med. 2018;16(1):8. View abstract. ↩︎

- Shah, J., Langmuir, V., and Gupta, S. K. “Feasibility and functionality of OROS melatonin in healthy subjects.” J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39(6):606-612. View abstract. ↩︎

- Waldhauser, F., Weiszenbacher, G., Frisch, H., Zeitlhuber, U., Waldhauser, M., and Wurtman, R. J. “Fall in nocturnal serum melatonin during prepuberty and pubescence.” Lancet. 2-18-1984;1(8373):362-365. View abstract. ↩︎

- Waldhauser, F., Waldhauser, M., Lieberman, H. R., Deng, M. H., Lynch, H. J., and Wurtman, R. J. “Bioavailability of oral melatonin in humans.” Neuroendocrinology. 1984;39(4):307-313. View abstract. ↩︎

- Andersen LP, Werner MU, Rosenkilde MM, et al. “Pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous melatonin in healthy volunteers.” BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016 Feb 19;17:8. View abstract. ↩︎

- Cagnacci, A., Elliott, J. A., and Yen, S. S. “Melatonin: a major regulator of the circadian rhythm of core temperature in humans.” J Clin Endocrinol. Metab. 1992;75(2):447-452. View abstract. ↩︎

- Deacon, S., English, J., and Arendt, J. “Acute phase-shifting effects of melatonin associated with suppression of core body temperature in humans.” Neurosci.Lett. 1994. 8-29-1994;178(1):32-34. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dawson, D., Gibbon, S., and Singh, P. ‘The hypothermic effect of melatonin on core body temperature: is more better?” J Pineal Res. 1996;20(4):192-197. View abstract. ↩︎

- Mundey K, Benloucif S, Harsanyi K, Dubocovich ML, Zee PC. Phase-dependent treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome with melatonin. Sleep. 2005 Oct;28(10):1271-8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1271. PubMed 16295212. ↩︎

- Ellis CM, Lemmens G, Parkes JD. ‘Melatonin and insomnia.” J Sleep Res. 1996;5:61-5. View abstract. ↩︎

- James SP, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, Mendelson WB. “Melatonin administration in insomnia.” Neuropsychopharmacology. 1990;3:19-23. View abstract. ↩︎

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Pandya R, et al. “Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment #108.” (Prepared by the Univ of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract#290-02-0023.) AHRQ Publ #05-E002-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. November 2004. ↩︎

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. “Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders.” PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. View abstract. ↩︎

- Givler D, Givler A, Luther PM, Wenger DM, Ahmadzadeh S, Shekoohi S, Edinoff AN, et al. “Chronic Administration of Melatonin: Physiological and Clinical Considerations.” Neurol Int. 2023 Mar 15;15(1):518-533. doi: 10.3390/neurolint15010031. PMID: 36976674; PMCID: PMC10053496. ↩︎

- DeMuro RL, Nafziger AN, Blask DE, et al. “The absolute bioavailability of oral melatonin.” J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40:781-4. View abstract. ↩︎

- Waldhauser, F., Waldhauser, M., Lieberman, H. R., Deng, M. H., Lynch, H. J., and Wurtman, R. J. “Bioavailability of oral melatonin in humans.” Neuroendocrinology. 1984;39(4):307-313. View abstract. ↩︎

- Madsen BK, Zetner D, Møller AM, Rosenberg J. “Melatonin for preoperative and postoperative anxiety in adults.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12:CD009861. View abstract. ↩︎

- Román Martinez M, García Aguilar E, Martin Vílchez S, et al. “Bioavailability of Oniria(®), a melatonin prolonged-release formulation, versus immediate-release melatonin in healthy volunteers.” Drugs R D. 2022;22(3):235-243. View abstract. ↩︎

- Madsen BK, Zetner D, Møller AM, Rosenberg J. “Melatonin for preoperative and postoperative anxiety in adults.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12:CD009861. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dollins AB, Zhdanova IV, Wurtman RJ, Lynch HJ, Deng MH. “Effect of inducing nocturnal serum melatonin concentrations in daytime on sleep, mood, body temperature, and performance.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(5):1824-1828. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1824 PubMed ↩︎

- Baandrup L, Lindschou J, Winkel P, Gluud C, Glenthoj BY. “Prolonged-release melatonin versus placebo for benzodiazepine discontinuation in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: A randomised, placebo-controlled, blinded trial.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17(7):514-24. View abstract. ↩︎

- Román Martinez M, García Aguilar E, Martin Vílchez S, et al. “Bioavailability of Oniria(®), a melatonin prolonged-release formulation, versus immediate-release melatonin in healthy volunteers.” Drugs R D. 2022;22(3):235-243. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dagan, Y., Zisapel, N., Nof, D., Laudon, M., and Atsmon, J. “Rapid reversal of tolerance to benzodiazepine hypnotics by treatment with oral melatonin: a case report.” Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997;7(2):157-160. ↩︎

- Zhdanova IV, Wurtman RJ, Regan MM, et al. “Melatonin treatment for age-related insomnia.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4727-30. View abstract. ↩︎

- Di, W. L., Kadva, A., Johnston, A., and Silman, R. “Variable bioavailability of oral melatonin.” N.Engl.J Med. 1997. 4-3-1997;336(14):1028-1029. View abstract. ↩︎

- Waldhauser, F., Waldhauser, M., Lieberman, H. R., Deng, M. H., et al. “Bioavailability of oral melatonin in humans.” Neuroendocrinology. 1984;39(4):307-313. View abstract. ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.