By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

May 15, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

While melatonin supplements do cause sleepiness, studies show that the impact of the supplements on insomnia is modest for most people.

Melatonin supplementation can provide meaningful benefits for individuals with lowered natural melatonin levels such as night workers and the elderly. It is also beneficial for treating delayed sleep phase—shifting the sleep clock of night owls. 1, 2 But the benefits of melatonin supplementation for most cases of insomnia appear to be lackluster.

Melatonin of various formulations may help people with insomnia fall asleep, but its effects are subtle. As one researcher put it: “The effectiveness of melatonin in initiating sleep is measurable but small in most people.” 3

Links to more information on melatonin:

Natural Melatonin vs. Supplements

Drug interactions & Precautions

Studies have shown that taking doses of melatonin that are higher than naturally occurring in the body—regardless of the time of day taken—cause sleepiness. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

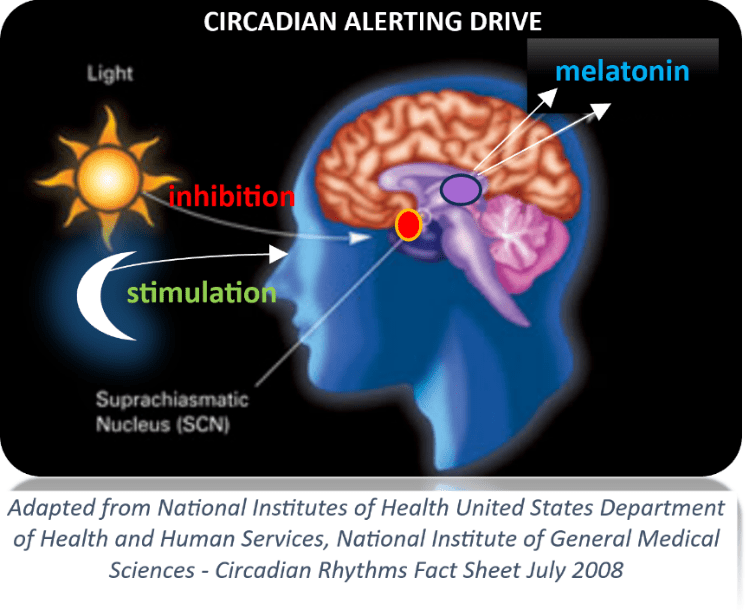

The sleep-promoting, hypnotic effect of melatonin is more pronounced when natural melatonin levels are low. Natural melatonin levels can decrease in some people such as with certain health conditions or genetic predispositions, or in situations where there’s reduced light exposure, travel across time-zones, taking certain pharmaceuticals or changes in the circadian clock that occur as we age. 9

Supplementation can help shift circadian rhythms. Based on when the dose is taken, melatonin can shift the bio-clock so that we wake-up and go to bed either earlier or later than we were going to bed and waking up before. 10, 11

But bright blue light has a much stronger effect on shifting the circadian clock than does melatonin supplementation. 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

One of the conditions for which melatonin supplements may provide substantial benefits is for people with delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS) also known as night owls. In this condition, melatonin supplementation—combined with other treatments—can help shift the sleep clock so that the person wakes up earlier and falls asleep sooner.

“Most clinical research shows that taking melatonin orally reduces the length of time needed to fall asleep and advances sleep onset time in young adults and children with DSPS,” according to an expert panel at NatMed Pro. The expert panel determined that “in addition to improving sleep, melatonin also improves measures of quality of life such as mental health, vitality, and bodily pain in young adults with DSPS.” 19 Benefits can last up to a year after stopping supplementation. 20

However, light therapy—not melatonin supplementation—is the most critical part of the treatment for DSPS. And adults with DSPS are born with a delayed sleep phase which—without treatment— persists throughout the lifespan. If they wish to keep to an earlier sleep schedule, they will need to maintain their treatment, of which melatonin is only one part.

Melatonin is effective for night owls because of its ability to alter circadian rhythms, which helps them defy their genetic night owl predisposition. But for other people with insomnia who are not night owls, melatonin simply does work as well.

Pooled data from numerous studies shows that melatonin treatment decreases the time it takes to fall asleep in healthy adults with insomnia who aren’t night owls by only about 7-12 minutes. 21 And these studies show that it only increases total sleep time by about 8 minutes. 22, 23 But some studies have found that patients taking melatonin supplements report modest improvements in their self-assessment of the quality of their sleep. 24, 25, 26, 27

Melatonin is best recommended as an adjunctive (supportive) treatment for insomnia rather than as a main treatment. Both American sleep specialists and British psychopharmacologists have long endorsed cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as first-line treatment for chronic insomnia. While these American sleep experts weakly recommend pharmaceutical sleep aids like Ambien for chronic insomnia and only for use with CBT-I, they’re not big on melatonin supplementation to support treatment using CBT-I. 28, 29

In 2008, asserting that most studies of melatonin had been small and of limited duration, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) declared that there was a lack of data on safety and efficacy of melatonin for the treatment of chronic insomnia. 30 In 2017, AASM endorsed melatonin supplements for circadian rhythm disorders like DPSD (night owls). But citing the same rationale as in 2008, they continued to avoid endorsing melatonin for sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia. 31

British psychopharmacologists on the other hand endorse melatonin supplementation in certain populations. 32

People with Lower Melatonin May Benefit More than Those with Normal Levels

People with insomnia, sleep disorders and co-occurring depression or fibromyalgia, 33 as well as people who are not exposed to sufficient natural light can have decreased levels of melatonin. 34

People who are ramping off of anti-anxiety medications known as benzodiazepines experience rebound insomnia and other sleep issues. Part of this may be because these drugs can depress melatonin levels. This may result in increased episodes of arousal during sleep, restlessness, and hang over effects of these medications.35

Benzodiazepines like Xanax are prescribed to suppress anxious feelings. But these drugs may also suppress the nocturnal rise in melatonin and dysregulate melatonin’s day-night rhythmicity interfering with normal sleep-wake cycles. 36

Abrupt discontinuation of benzodiazepines like Xanax can result in life-threatening side effects. Always consult your prescribing physician before making any changes to your medications and supplements.

As we age, our circadian rhythms have been found to change. The amount of nighttime melatonin present when we were younger drops as we age. 37

Over 55: Melatonin May Be Just What the Doctor Ordered

Natural melatonin production declines with age. By age 20 to 30, we have two thirds of the melatonin we had as young children. And by age 40, our melatonin levels are only half of what they were when we were kids. By our mid to late 60’s, melatonin production declines to 20% of the melatonin of we had as children.

Data shows that melatonin can be helpful for older people with insomnia. 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45

A British Medical Journal study found that patients over age 64 taking prolonged-release melatonin (2 mg) decreased the time needed to fall asleep and had additional benefits for sleep. This study also demonstrated a reduction in daytime symptoms due to poor sleep. The study participants showed no signs of the tolerance seen in pharmaceuticals and they maintained and even increased these improvements over a 6-month period. The study confirmed findings of prior studies. 46

A British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement gave a first-line endorsement in 2010 to prolonged-release melatonin for chronic insomnia in persons over 55. 47

Different studies of elder insomniacs have used various dosing regimens including sustained-release, fast-release, or slow-release melatonin preparations at doses of 2-3 mg before bedtime.

Prolonged-release preparations may help prevent nighttime wakefulness in older individuals. Whereas immediate-release preparations decrease the time it takes older insomniacs to fall asleep. 48, 49

People with Anxiety & Depression: the Evidence is Less Clear

For people with depressed melatonin levels due to lack of light, the best thing is to restore natural melatonin rhythms by getting daytime sunlight—like getting out in the garden in the bright, early-morning sun. Of course, just like in an eclipse, it is not safe to look directly at the sun.

Some studies show that melatonin supplementation may help restore sleep quality, especially while ramping down from anti-anxiety medications, which suppress melatonin levels. 50, 51 Other studies have found inconsistent or no effects of supplementation on sleep. 52, 53

There is evidence that melatonin alone or melatonin in combination with other sleep therapies such as light therapy seems to be beneficial for insomnia in patients with other co-occurring conditions like depression, which can suppress melatonin levels. Preliminary research using 2-12 mg of melatonin for up to a month has been found to improve sleep—but not depression—in patients with depression. 54, 55

Despite the fact that patients with depression having reduced melatonin levels, 56 most studies don’t show a benefit of supplementation in reducing depressive symptoms. 57

Melatonin supplementation might increase depressive symptoms in some people.

Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before taking or discontinuing any drug or supplement.

For information about the safety of melatonin supplements, click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using this website, you agree to accept MoodChangeMedicine.com website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Givler D, Givler A, Luther PM, Wenger DM, Ahmadzadeh S, Shekoohi S, Edinoff AN, et al. “Chronic Administration of Melatonin: Physiological and Clinical Considerations.” Neurol Int. 2023 Mar 15;15(1):518-533. doi: 10.3390/neurolint15010031. PMID: 36976674; PMCID: PMC10053496. ↩︎

- “Melatonin Monograph” NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database 3/8/2024. Last modified on 3/7/2024. Accessed April, 2024. ↩︎

- Givler D, Givler A, Luther PM, Wenger DM, Ahmadzadeh S, Shekoohi S, Edinoff AN, et al. “Chronic Administration of Melatonin: Physiological and Clinical Considerations.” Neurol Int. 2023 Mar 15;15(1):518-533. doi: 10.3390/neurolint15010031. PMID: 36976674; PMCID: PMC10053496. ↩︎

- Dollins AB, Lynch HJ, Wurtman RJ, et al. “Effect of pharmacological daytime doses of melatonin on human mood and performance.” Psychopharmacol (Berl). 1993;112:490-6. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dollins AB, Zhdanova IV, Wurtman RJ, Lynch HJ, Deng MH. “Effect of inducing nocturnal serum melatonin concentrations in daytime on sleep, mood, body temperature, and performance.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(5):1824-1828. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.5.1824 PubMed ↩︎

- Waldhauser F, Saletu B, Trinchard-Lugan I. “Sleep laboratory investigations on hypnotic properties of melatonin.” Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1990;100:222-6. View abstract. ↩︎

- Cajochen, C., Krauchi, K., von Arx, M. A., Mori, D., Graw, P., and Wirz-Justice, A. “Daytime melatonin administration enhances sleepiness and theta/alpha activity in the waking EEG.” Neurosci.Lett. 4-5-1996;207(3):209-213. View abstract. ↩︎

- Tzischinsky, O. and Lavie, P. “Melatonin possesses time-dependent hypnotic effects.” Sleep. 1994;17(7):638-645. View abstract. ↩︎

- Nave R, Peled R, Lavie P. “Melatonin improves evening napping.” Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;275:213-6. View abstract. ↩︎

- Cagnacci, A., Elliott, J. A., and Yen, S. S. “Melatonin: a major regulator of the circadian rhythm of core temperature in humans.” J Clin Endocrinol.Metab. 1992;75(2):447-452. View abstract. ↩︎

- Rajaratnam, S. M., Middleton, B., Stone, B. M., Arendt, J., and Dijk, D. J. “Melatonin advances the circadian timing of EEG sleep and directly facilitates sleep without altering its duration in extended sleep opportunities in humans.” J Physiol. 2004. 11-15-2004;561(Pt 1):339-351. View abstract. ↩︎

- Cagnacci, A., Soldani, R., and Yen, S. S. “Contemporaneous melatonin administration modifies the circadian response to nocturnal bright light stimuli.” Am J Physiol. 1997;272(2 Pt 2):R482-R486. View abstract. ↩︎

- Deacon, S. and Arendt, J. “Melatonin-induced temperature suppression and its acute phase-shifting effects correlate in a dose-dependent manner in humans.” Brain Res. 1995. 8-7-1995;688(1-2):77-85. View abstract. ↩︎

- Hatonen, T., Alila, A., and Laakso, M. L. “Exogenous melatonin fails to counteract the light-induced phase delay of human melatonin rhythm.” Brain Res. 1996. 2-26-1996;710(1-2):125-130. View abstract. ↩︎

- Lewy AJ, Ahmed S, Jackson JM, Sack RL. “Melatonin shifts human circadian rhythms according to a phase-response curve.” Chronobiol Int. 1992;9:380-92. View abstract. ↩︎

- Lewy, A. J. and Sack, R. L. “Exogenous melatonin’s phase-shifting effects on the endogenous melatonin profile in sighted humans: a brief review and critique of the literature.” J Biol Rhythms. 1997;12(6):588-594. View abstract. ↩︎

- Steinlechner, S. Melatonin as a chronobiotic: “PROS and CONS.” Acta Neurobiol.Exp (Warsz.) 1996;56(1):363-372. View abstract. ↩︎

- Zaidan, R., Geoffriau, M., Brun, J., Taillard, J., Bureau, C., et al. “Melatonin is able to influence its secretion in humans: description of a phase-response curve.” Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60(1):105-112. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Melatonin Monograph” NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database 3/8/2024. Last modified on 3/7/2024. Accessed April, 2024. ↩︎

- Dagan, Y., Yovel, I., Hallis, D., Eisenstein, M., and Raichik, I. “Evaluating the role of melatonin in the long-term treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS).” Chronobiol.Int. 1998;15(2):181-190. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Melatonin Monograph” NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database 3/8/2024. Last modified on 3/7/2024. Accessed April, 2024. ↩︎

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Hooton N, et al. “The efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for primary sleep disorders. A meta-analysis.” J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1151-8. View abstract. ↩︎

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. “Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders.” PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. View abstract. ↩︎

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Pandya R, et al. “Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment #108.” (Prepared by the Univ of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract#290-02-0023.) AHRQ Publ #05-E002-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. November 2004.

88290 ↩︎ - Ellis CM, Lemmens G, Parkes JD. “Melatonin and insomnia.” J Sleep Res. 1996;5:61-5. View abstract. ↩︎

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. “Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders.” PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. View abstract. ↩︎

- James SP, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, Mendelson WB. “Melatonin administration in insomnia.” Neuropsychopharmacology. 1990;3:19-23. View abstract. ↩︎

- Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. “Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults.” J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Oct 15. 4(5):487-504. [Guideline] ↩︎

- Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. “Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline.” J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Feb 15. 13 (2):307-349. ↩︎

- Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. “Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults.” J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Oct 15. 4(5):487-504. [Guideline] ↩︎

- Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. “Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline.” J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Feb 15. 13 (2):307-349. ↩︎

- Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ, Alford C, et al. “British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders.” J Psychopharmacol. 2010;2411:1577-1601, 20813762. ↩︎

- von Bahr C, Ursing C, Yasui N, et al. “Fluvoxamine but not citalopram increases serum melatonin in healthy subjects – an indication that cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 hydroxylate melatonin.” Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:123-7. View abstract. ↩︎

- Mishima K, Okawa M, Shimizu T, Hishikawa Y. “Diminished melatonin secretion in the elderly caused by insufficient environmental illumination.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:129-34. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dawson D, Encel N. Melatonin and sleep in humans. Journal of Pineal Research. 1993;15(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Kabuto M, Namura I, Saitoh Y. “Nocturnal enhancement of plasma melatonin could be suppressed by benzodiazepines in humans.” Endocrinol Jpn. 1986;33405- 414Google Scholar Crossref ↩︎

- Sack, R. L., Lewy, A. J., Erb, D. L., Vollmer, W. M., and Singer, C. M. “Human melatonin production decreases with age.” J Pineal Res. 1986;3(4):379-388. View abstract. ↩︎

- Hughes RJ, Sack RL, Lewy AJ. “The role of melatonin and circadian phase in age-related sleep- maintenance insomnia: assessment in a clinical trial of melatonin replacement.” Sleep. 1998;21(1):52-68. View abstract. ↩︎

- Haimov I, Lavie P, Laudon M, et al. “Melatonin replacement therapy of elderly insomniacs.” Sleep. 1995;18:598-603. View abstract. ↩︎

- Garfinkel D, Laudon M, Nof D, Zisapel N. “Improvement of sleep quality in elderly people by controlled-release melatonin.” Lancet. 1995;346:541-4. View abstract. ↩︎

- Lemoine P, Nir T, Laudon M, Zisapel N. “Prolonged-release melatonin improves sleep quality and morning alertness in insomnia patients aged 55 years and older and has no withdrawal effects.” J Sleep Res. 2007;16(4):372-80. View abstract. ↩︎

- Luthringer R, Muzet M, Zisapel N, Staner L. “The effect of prolonged-release melatonin on sleep measures and psychomotor performance in elderly patients with insomnia.” Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(5):239-49. View abstract. ↩︎

- Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. “Efficacy of prolonged release melatonin in insomnia patients aged 55-80 years: quality of sleep and next-day alertness outcomes.” Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(10):2597-605. View abstract. ↩︎

- Wade, A. G., Crawford, G., Ford, I., McConnachie, A., Nir, T., Laudon, M., and Zisapel, N. “Prolonged release melatonin in the treatment of primary insomnia: evaluation of the age cut-off for short- and long-term response.” Curr.Med.Res.Opin. 2011;27(1):87-98. View abstract. ↩︎

- Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. “Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with prolonged release melatonin for 6 months: a randomized placebo controlled trial on age and endogenous melatonin as predictors of efficacy and safety.” BMC Med. 2010 Aug 16;8:51: biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/8/51. ↩︎

- Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. “Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with prolonged release melatonin for 6 months: a randomized placebo controlled trial on age and endogenous melatonin as predictors of efficacy and safety.” BMC Med. 2010 Aug 16;8:51: biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/8/51. ↩︎

- Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ, Alford C, et al. “British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders.” J Psychopharmacol. Nov. 2010;2411:1577-1601, 20813762. ↩︎

- Haimov I, Lavie P, Laudon M, et al. “Melatonin replacement therapy of elderly insomniacs.” Sleep. 1995;18:598-603. View abstract. ↩︎

- Hughes RJ, Sack RL, Lewy AJ. “The role of melatonin and circadian phase in age-related sleep- maintenance insomnia: assessment in a clinical trial of melatonin replacement.” Sleep. 1998;21(1):52-68. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dawson D, Encel N. Melatonin and sleep in humans. Journal of Pineal Research. 1993;15(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Garfinkel D, Zisapel N, Wainstein J, Laudon M. “Facilitation of Benzodiazepine Discontinuation by Melatonin: A New Clinical Approach.” Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(20):2456–2460. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.20.2456 jamainternalmedicine ↩︎

- Lähteenmäki R, Puustinen J, Vahlberg T, et al. “Melatonin for sedative withdrawal in older patients with primary insomnia: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial.” Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77(6):975-85. View abstract. ↩︎

- Wright A, Diebold J, Otal J, et al. “The Effect of Melatonin on Benzodiazepine Discontinuation and Sleep Quality in Adults Attempting to Discontinue Benzodiazepines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Drugs Aging. 2015;32(12):1009-18. View abstract. ↩︎

- Brusco LI, Fainstein I, Marquez M, Cardinali DP. “Effect of melatonin in selected populations of sleep-disturbed patients.” Biol Signals Recept. 1999;8:126-31. View abstract. ↩︎

- Dolberg OT, Hirschmann S, Grunhaus L. “Melatonin for the treatment of sleep disturbances in major depressive disorder.” Am J Psychiatr. 1998;155:1119-21. View abstract. ↩︎

- von Bahr C, Ursing C, Yasui N, et al. “Fluvoxamine but not citalopram increases serum melatonin in healthy subjects – an indication that cytochrome P450 CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 hydroxylate melatonin.” Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:123-7. View abstract. ↩︎

- Hansen MV, Danielsen AK, Hageman I, Rosenberg J, Gögenur I. “The therapeutic or prophylactic effect of exogenous melatonin against depression and depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(11):1719-28. View abstract. ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.