By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

May 26, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid used by the body to make proteins, neurotransmitters, hormones and vitamin B3. It must be obtained from food. It’s found in abundance in foods like turkey, soybeans, egg whites, chicken, pumpkin seeds, spinach, and bananas.

The hormones serotonin and melatonin both play a role in regulating sleep. All the serotonin and melatonin in the body is made from the tryptophan we get from our diets.

This website’s article “Are Tryptophan Supplements Effective for Insomnia?” explains that tryptophan helps people fall asleep a little bit faster and may also decrease time spent awake after sleep onset, according a number of small-scale clinical studies.

But the benefits of tryptophan for sleep might be better achieved by eating a sleep-boosting diet then from taking supplements.

Eating foods that are rich in tryptophan, particularly from plants, is linked to increased total sleep time. 1, 2 If we eat too little protein, it can lead to a deficiency of tryptophan, which can lead to sleep disturbances. 3

Whether from food or supplements, the sleep-promoting effects of tryptophan seem to be dramatically effected by a number of different factors including timing, dose, nutrients consumed with it, deficiencies of other dietary nutrients and problems with tryptophan absorption in the GI tract—something which is largely based on the microorganisms that colonize our the gut. The ability of tryptophan to work optimally for sleep might be more about these factors than it is about whether the tryptophan comes from food or supplements.

For example, just buying a tryptophan supplement and following the directions on the label might not lead to improved sleep. The dosage and timing of how tryptophan supplements are taken could impact their efficacy. 4 The body’s use of tryptophan may also be boosted by the time of day when it is consumed based on the exposure to the light of the morning sun. 5

For some people, doses in excess of 1 gram worked on the first night they took it, according to research. 6 For others, particularly people who have long-term or more severe insomnia, repeated low doses of tryptophan over time resulted in benefits occurring late in the treatment period or even after they stopped taking tryptophan. Some need very high doses to get good results—doses that are higher than the 5 grams per day that has been shown to be safe.

One study found beneficial results by having study participants take days off of supplementation. 7

Tryptophan from food combined with early morning sun might improve sleep better than taking the supplement. A study found that eating a tryptophan-rich breakfast combined with early-morning light exposure boosts evening melatonin levels. Melatonin is the body’s sleep promoting hormone. 8

Diet can greatly influence the effectiveness of tryptophan. So can other nutrients we get from food, which are needed to manufacture hormones like serotonin and melatonin.

For example, the amount and type of fat we eat can also affect sleep quality. Fatty fish, a good source of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, may improve sleep. 9, 10 It may be related to the impact that omega-3 fatty acids have on the synthesis of the sleep-hormone melatonin. 11 The fatty acids impact gut bacteria, which are key to the absorption of tryptophan as well as of many other nutrients we get from food.

High consumption of saturated fatty acid can cause deceases in slow-wave (restorative) sleep and increase the number of nighttime awakenings. 12 Saturated fat consumption has a big impact on the health of the bacteria that line the GI tract—the microbiota—upon which we depend to help us absorb and utilize dietary nutrients.

And it’s not only the fats we eat, it’s also our carb intake that can dramatically affect how tryptophan functions in the body. Blood sugar can spike when we eat high amounts of simple sugars and carbohydrates combined with very low amounts of other macronutrients like protein intake of 5% or less.13 This can change the amount of tryptophan that can pass through the blood-brain barrier and increase levels of tryptophan in the brain. The amount of tryptophan getting into the brain is crucial to the amount of melatonin the brain can manufacture. Melatonin is the main sleep-regulating hormone in the body.

This may be part of the reason why we feel sleepy after eating a lot of starchy foods that contain little fat, fiber or protein. This can happen when we eat large quantities white bread, plain white rolls, plain pasta noodles, white rice or pretzels away from other foods that contain significant amounts of other nutrients like fat and protein. 14 The other reason that we feel sleepy after a high-carb meal is that carb intake such as this raises blood sugar dramatically, which later leads to sudden decreases in blood sugar and a fall in energy levels.

There are other factors that impact tryptophan’s absorption and affect the levels of tryptophan reaching the brain where it is used to make the sleep-hormone melatonin.

How Tryptophan Works: Not as Simple as Popping a Pill

The body uses dietary tryptophan to produce serotonin. And from serotonin, the body makes the melatonin.

Serotonin is a mood-regulating neurotransmitter; it also plays a role in sleep. 15, 16 Antidepressants called Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) like Zoloft boost serotonin levels.

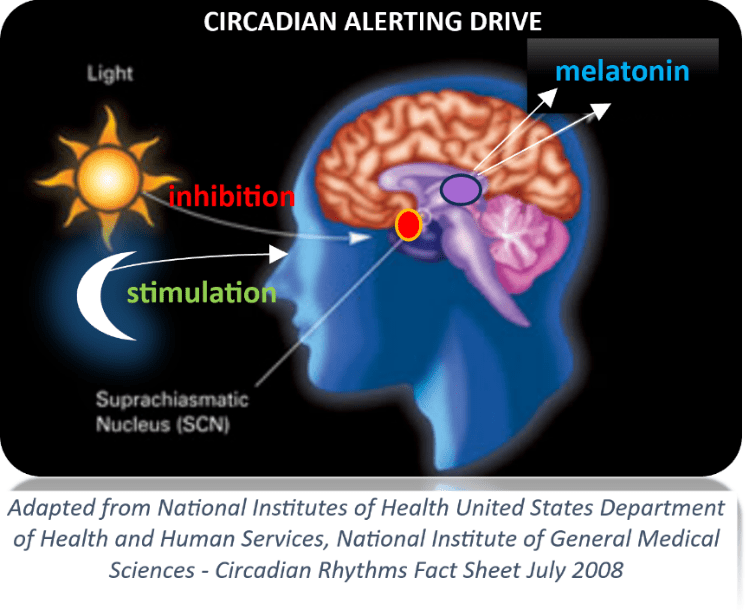

Melatonin, the body’s main sleep-promoting hormone, is a chief regulator of circadian sleep-wake cycles.

Natural melatonin production is fundamental to all life on earth and is vital for sleep and overall health. But some attribute the sedating effects of tryptophan more to its ability to boost serotonin than its role in melatonin production. 17 Precisely how it causes sedation is not known, including how much of it is related to increased production of melatonin versus serotonin. It is likely related to its effects on both of these important hormones.

Synthesis of melatonin in the brain begins with tryptophan from food. Tryptophan travels to the brain via the bloodstream and then inside the brain—where, cued by changes in light hitting the eyes—the pineal gland converts tryptophan into serotonin and in turn, into melatonin.

There are a number of ways melatonin and serotonin production can go in undesirable directions.

Tryptophan is also used by the body in the process of making structural proteins that form body tissues and nicotinamide, the water-soluble form of vitamin B3 or niacin. (In this process, a number of metabolites are formed including kynurenine, kynurenic acid, and quinolinic acid, which are implicated in depression.) 18

The lack of certain dietary nutrients can defeat the process of turning tryptophan into serotonin and serotonin into melatonin. Nutrient deficiencies can deprive the body of the cofactors—other nutrients—required for enzymatic reactions that transform tryptophan into these sleep-impacting hormones. Such deficiencies divert production away from serotonin and melatonin into making other substances like niacin or protein. These processes are be affected by diet and exercise.

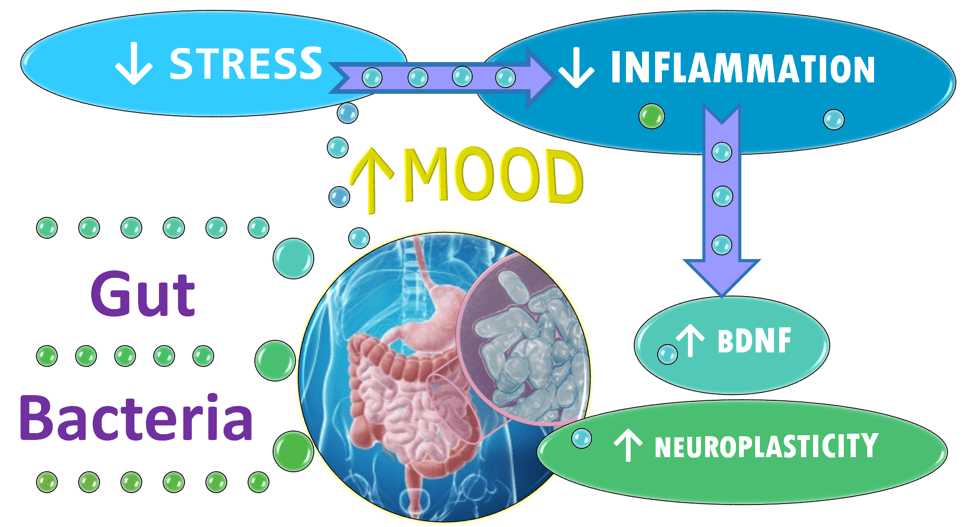

Bacteria that colonize the GI tract determine how much tryptophan is absorbed and available for the manufacture of key mood and sleep-regulating substances in the body. If the bacteria in the gut—the microbiota—are compromised it impacts the absorption and availability of tryptophan, and therefore how much serotonin is manufactured both in the gut and in the brain. 19 Gut bacteria health can be compromised by frequent use of oral antibiotics, diets low in fiber and indigestible sugars and/or diets high in ultra-processed foods.

Tryptophan must compete with other amino acids found in food for entry into the brain. Because of this competition, tryptophan supplements can be affected by the types of proteins eaten with it, potentially reducing supplement efficacy.

Proteins are made of different amino acids of which tryptophan is one. An experiment showed that consumption of a tryptophan-free protein drink, high in other amino acids, had a negative impact on sleep continuity. 20 So when we consume tryptophan with other amino acids this can compromise the amount of tryptophan getting into the brain.

Melatonin can also be made in the GI tract from tryptophan in the diet. 21 The melatonin made in the gut can cross the blood-brain-barrier. 22 The extent to which gut-derived melatonin impacts sleep and circadian rhythms is currently under investigation.

Bacteria that colonize the gut—the microbiota—convert tryptophan into serotonin. Serotonin is then converted into melatonin by cells in the GI tract. If there’s any disturbances in the microbiota, it can reduce the availability of tryptophan to produce melatonin.

The circadian sleep-awake clock is largely controlled in the brain, where it’s under the regulation of brain-derived melatonin. Such melatonin production is controlled by the daily cycle of daytime light and the darkness of night. That’s likely why getting early morning sunlight in combination with eating tryptophan-rich food helps boost the effects of dietary tryptophan. 23

But if the microbiota is compromised, it can reduce the amount of tryptophan we absorb. A drop in tryptophan dramatically inhibits serotonin synthesis and reduces tryptophan concentrations in the brain, resulting in a decrease in brain levels of serotonin in both humans and animals.24 Because both serotonin and tryptophan can be converted to melatonin and because serotonin, by itself has sleep-promoting benefits, this may have a negative impact on sleep.

Researchers on the cutting edge of science are now saying that the population of gut bacteria also plays a major role in circadian rhythms—the body’s sleep clock—and in regulating brain cell function. 25

Vitamins & Minerals Crucial for Serotonin and Melatonin Manufacture

In order for the body to turn tryptophan into serotonin and melatonin, it needs other nutrients.

Diet is the best way to get these nutrients, which include iron, magnesium, calcium, vitamin B6 and folic acid (B9), niacin, Vitamin C and likely zinc. Vitamin D and the omega-3 fatty acids control serotonin synthesis. 26 Some nutrients like magnesium and vitamin D may be harder to get from food.

And as we’ve seen, a robust and varied population of gut bacteria is key to absorbing nutrients and for the manufacture of the mood-related neurotransmitter serotonin and the sleep hormone melatonin. The microbiota also regulates are our sleep-clocks. So in addition to eating a diet of nutrient-rich foods, we also need to eat to sustain a healthy colony of gut bugs.

Food to Feed a Mood-Boosting Biota

In some cases, people can establish and maintain a healthy gut microbiota by consuming a diet with ample amounts of probiotic and prebiotic foods. In other cases, people may need to take probiotic supplements. Probiotic foods contain live-bacteria such as dairy and non-dairy yogurts, kombucha tea and other fermented foods. Prebiotic foods contain indigestible carbohydrates like fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and inulin fibers found in foods like bananas, onions, sunchokes and other foods.

Evidence suggests that our gut microbiota has an enormous influence over our mental-emotional state. 27, 28 Based on their antidepressant and anxiolytic effects, gut bacteria beneficial to mental health have been called psychobiotics. 29

Someday doctors might routinely prescribe psychobiotics for their patients with anxiety and depression.

To find out how tryptophan plays a role in depression and recovery from it, click link below:

Links to more information about tryptophan:

Tryptophan & Its Alternatives for Depression, Anxiety & Sleep

Are Tryptophan Supplements Effective Insomnia?

Are Tryptophan Supplements Effective for Anxiety & Depression?

Low Tryptophan = Low Serotonin. Does Low Serotonin = Depression?

To find out more about our services, click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Sejbuk M, Mirończuk-Chodakowska I, Witkowska AM. “Sleep Quality: A Narrative Review on Nutrition, Stimulants, and Physical Activity as Important Factors.” Nutrients. 2022 May 2;14(9):1912. doi: 10.3390/nu14091912. PMID: 35565879; PMCID: PMC9103473. ↩︎

- Martínez-Rodríguez A., Rubio-Arias J., Ramos-Campo D.J., Reche-García C., Leyva-Vela B., Nadal-Nicolás Y. “Psychological and sleep effects of tryptophan and magnesium-enriched mediterranean diet in women with fibromyalgia.” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:2227. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar ↩︎

- Sutanto C.N., Loh W.W., Toh D.W.K., Lee D.P.S., Kim J.E. “Association between dietary protein intake and sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults in Singapore.” Front. Nutr. 2022;9:832341. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.832341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Riemann D, Feige B, Hornyak M, Koch S, Hohagen F, Voderholzer U. “The tryptophan depletion test: impact on sleep in primary insomnia – a pilot study.” Psychiatry Res. 2002 Mar 15;109(2):129-35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00010-0. PMID: 11927137. ↩︎

- Fukushige H, Fukuda Y, Tanaka M, Inami K, Wada K, Tsumura Y, Kondo M, Harada T, Wakamura T, Morita T. “Effects of tryptophan-rich breakfast and light exposure during the daytime on melatonin secretion at night.” J Physiol Anthropol. 2014 Nov 19;33(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1880-6805-33-33. PMID: 25407790; PMCID: PMC4247643. ↩︎

- Schneider-Helmert, Dietrich and Cheryl L. Spinweber. “Evaluation of l-tryptophan for treatment of insomnia: A review.”Psychopharmacology. 2004. 89 (2004): 1-7. ↩︎

- Schneider-Helmert D. “Interval therapy with L-tryptophan in severe chronic insomniacs. A predictive laboratory study.” Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1981;16(3):162-73. doi: 10.1159/000468491. PMID: 7033160. ↩︎

- Fukushige H, Fukuda Y, Tanaka M, Inami K, Wada K, Tsumura Y, Kondo M, Harada T, Wakamura T, Morita T. “Effects of tryptophan-rich breakfast and light exposure during the daytime on melatonin secretion at night.” J Physiol Anthropol. 2014 Nov 19;33(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1880-6805-33-33. PMID: 25407790; PMCID: PMC4247643. ↩︎

- Lavialle M., Champeil-Potokar G., Alessandri J.M., Balasse L., Guesnet P., Papillon C., Pévet P., Vancassel S., Vivien-Roels B., Denis I. “An (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid–deficient diet disturbs daily locomotor activity, melatonin rhythm, and striatal dopamine in syrian hamsters.” J. Nutr. 2008;138:1719–1724. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.9.1719. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Sejbuk M, Mirończuk-Chodakowska I, Witkowska AM. “Sleep Quality: A Narrative Review on Nutrition, Stimulants, and Physical Activity as Important Factors.” Nutrients. 2022 May 2;14(9):1912. doi: 10.3390/nu14091912. PMID: 35565879; PMCID: PMC9103473. ↩︎

- St-Onge M.-P., Roberts A., Shechter A., Choudhury A.R. “Fiber and saturated fat are associated with sleep arousals and slow wave sleep.” J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2016;12:19–24. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- St-Onge M.-P., Roberts A., Shechter A., Choudhury A.R. “Fiber and saturated fat are associated with sleep arousals and slow wave sleep.” J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2016;12:19–24. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Gangwisch J., Hale L., St-Onge M.-P., Choi L., LeBlanc E.S., Malaspina D., Opler M.G., Shadyab A.H., Shikany J.M., Snetselaar L., et al. “High glycemic index and glycemic load diets as risk factors for insomnia: Analyses from the women’s health initiative.” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020;111:429–439. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Sejbuk M, Mirończuk-Chodakowska I, Witkowska AM. Sleep Quality: A Narrative Review on Nutrition, Stimulants, and Physical Activity as Important Factors. Nutrients. 2022 May 2;14(9):1912. doi: 10.3390/nu14091912. PMID: 35565879; PMCID: PMC9103473 ↩︎

- Birdsall TC. “5-Hydroxytryptophan: a clinically-effective serotonin precursor.” Altern Med Rev. 1998 Aug;3(4):271-80. PMID: 9727088. ↩︎

- Portas CM, Bjorvatn B, Ursin R. “Serotonin and the sleep/wake cycle: special emphasis on microdialysis studies.” Prog Neurobiol. 2000 Jan;60(1):13-35. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00097-5. PMID: 10622375. ↩︎

- Lieberman HR, Corkin S, Spring BJ. “The effects of dietary neurotransmitter precursors on human behavior.” Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:366-70. View abstract. ↩︎

- Hiratsuka C, Fukuwatari T, Sano M, Saito K, Sasaki S, Shibata K. “Supplementing healthy women with up to 5.0 g/d of L-tryptophan has no adverse effects.” J Nutr. 2013 Jun;143(6):859-66. View abstract. ↩︎

- O’Farrell K, Harkin A. “Stress-related regulation of the kynurenine pathway: relevance to neuropsychiatric and degenerative disorders.” Neuropharmacology. 2017. 112 (Pt B) (2017), pp. 307-323 ↩︎

- Riemann D, Feige B, Hornyak M, Koch S, Hohagen F, Voderholzer U. “The tryptophan depletion test: impact on sleep in primary insomnia – a pilot study.” Psychiatry Res. 2002 Mar 15;109(2):129-35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00010-0. PMID: 11927137. ↩︎

- Chen CQ, Fichna J, Bashashati M, Li YY, Storr M. “Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut.” World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep 14;17(34):3888-98. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i34.3888. PMID: 22025877; PMCID: PMC3198018 ↩︎

- Chen CQ, Fichna J, Bashashati M, Li YY, Storr M. “Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut.” World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep 14;17(34):3888-98. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i34.3888. PMID: 22025877; PMCID: PMC3198018 ↩︎

- Fukushige H, Fukuda Y, Tanaka M, Inami K, Wada K, Tsumura Y, Kondo M, Harada T, Wakamura T, Morita T. “Effects of tryptophan-rich breakfast and light exposure during the daytime on melatonin secretion at night.” J Physiol Anthropol. 2014 Nov 19;33(1):33. doi: 10.1186/1880-6805-33-33. PMID: 25407790; PMCID: PMC4247643. ↩︎

- Wang Z, Liu S, Xu X, Xiao Y, Yang M, Zhao X, Jin C, Hu F, Yang S, Tang B, Song C, Wang T. “Gut Microbiota Associated With Effectiveness And Responsiveness to Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Improving Trait Anxiety.” Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Feb 24;12:719829. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.719829. PMID: 35281444; PMCID: PMC8908961. ↩︎

- Mu C, Yang Y, Zhu W “Gut microbiota: the brain peacekeeper.” Front Microbiol. 2016. 7 (2016), p. 345 ↩︎

- Peuhkuri K, Sihvola N, Korpela R. “Dietary factors and fluctuating levels of melatonin.” Food Nutr Res. 2012;56. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v56i0.17252. ↩︎

- Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. “The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems.” Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(2):203-209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Mayer EA, Savidge T, Shulman RJ. “Brain-gut microbiota interactions and functional bowel disorders.” Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1500-1512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Cheng, L.-H., Liu, Y.-W., Wu, C.-C., Wang, S., & Tsai, Y.-C. “Psychobiotics in mental health, neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders.” Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, 27(3), 632–648. 2019. doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2019.01.002 ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.