By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

May 28, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid used by the body to make proteins, neurotransmitters, hormones and vitamin B3. It must be obtained from food. It’s found in abundance in turkey, soybeans, egg whites, chicken, pumpkin seeds, spinach, and bananas.

Tryptophan from the foods we eat travels from the gut to the brain via the bloodstream where it is converted into serotonin. Some of the serotonin gets converted into melatonin.

Serotonin has gained a reputation for its role in mood-regulation. Doctors treat depression with SSRI antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) which boost serotonin levels in the brain. So it’s not surprising that a lot of people think that low serotonin causes depression.

Since serotonin is made from tryptophan, serotonin levels can be reduced by limiting the amount of tryptophan in the diet. Putting patients on special diets with very low amounts of tryptophan can cause a recurrence in depression patients who were treated with SSRIs antidepressants. 1, 2

But we don’t know if the reason for the recurrence of depression is from low serotonin or if it is related to an alteration by SSRIs in how the body regulates the tryptophan-to-serotonin pathway.

Some healthy people on a low-tryptophan diet may experience depressive symptoms, studies have found, 3, 4 Other studies have found that depressed persons have decreased blood levels of tryptophan. 5, 6 A study of a group of depressed women found that they had very significantly reduced plasma levels of free tryptophan and it also found that their tryptophan levels increased significantly after recovery from depression. 7

But, despite these findings of low tryptophan in people with depression, there is a major controversy over whether or not depression is caused by low tryptophan and it’s consequence—low serotonin. 8, 9

“In healthy participants with no risk factors for depression, tryptophan depletion does not produce clinically significant changes in mood rising to the level of depression,” according to the author of a 2015 article in the Journal of the World Psychiatry Association. 10

The results of a 2023 review of studies including 566 mostly healthy volunteers found no effect from tryptophan-restricting diets. Further studies of a combined total of 749 participants also found no effect. But a study of 75 subjects found weak evidence of an effect of tryptophan restriction in those with a family history of depression. 11

Some researchers assert that the results of these and other studies collectively show there is no consistent evidence of an association between serotonin and depression. That led these researchers to conclude that there is “no support for the hypothesis that depression is caused by lowered serotonin activity or concentrations.” 12

What we can conclude from the controversy in the scientific literature is that the idea that low serotonin is the cause of depression is on shaky ground.

If serotonin is not the main biological driver of depression, what explains the decreased tryptophan levels in in people with depression and the rise in those levels after they recovered?

Chronic or intensive stress might be driving the drop in tryptophan levels seen in some of the scientific literature. Stress might be changing how tryptophan is metabolized.

Is the Culprit Stress or Low Serotonin?

Stress hormones—which get pumped out if you are worried about losing your job, finances or fighting with your family—are known to diminish blood levels of tryptophan. 13

The drop in circulating tryptophan levels may be due to its diversion into making other sorts of neurochemicals, some of which can be detrimental.

Psychological stress has been observed to alter the biochemical pathways that convert tryptophan into serotonin. This can shift the balance in the brain away from neuroprotective physiology towards neurotoxic physiology. 14 This may be part of the reason that brain structures such as the hippocampus shrink during prolonged depressive episodes. Rather than low serotonin levels triggering depression, the trigger may be a shift in tryptophan metabolism to generate neurotoxins instead of serotonin. Such neurotoxins could attack brain tissue.

Stress can trigger inflammation and mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression. 15 Even stressed mice show behaviors that are indicative of depression and anxiety. 16

Low tryptophan levels seen in the biology of depression could be just another manifestation of biochemical processes triggered by high stress levels. This may explain why prolonged stress often precedes episodes of depression.

The biochemistry of stress was elegantly elucidated by a 2020 article. Liver metabolism—which can be altered by stress—is responsible for upwards of 90% of total tryptophan available for making hormones like serotonin and melatonin, the authors note. 17 When we are not stressed, the more tryptophan present, the more serotonin that can be produced. When stress hormones like cortisol chronically increase, it alters this metabolic pathway. The altered pathway results in tryptophan’s increased conversion into metabolites that have damaging effects on the brain. This changes the biochemical balance in the brain, shifting it from a neuroprotective state into a more neurotoxic one. Such shifts are implicated in mental health conditions like depression. 18

Chronic stress causes repeated activation of the fight-or-flight response—the HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis)—releasing stress hormones that generate inflammation. 19

The strong linkage between stress, inflammation and depression is shown by how spiking inflammation triggers an increase in an inflammation-fighting enzyme called IDO. 20 This liver enzyme—IDO—shunts tryptophan that would have been turned into serotonin into making vitamin B3 and other metabolites, some of which are neurotoxic. That shift in the relative balance of tryptophan metabolites in the brain toward more neurotoxic tryptophan break-down products is what some researchers believe drives depression biology. 21, 22, 23

Researchers point to stress-induced dysregulation in the metabolic pathway of tryptophan as having a “deleterious effect” on mental health conditions including major depressive disorder. 24

These neurotoxic states created by the shunting of tryptophan into neurotoxic metabolites might add fuel to the pre-existing inflammmatory fire in the brain. This further adds to the inflammation created by the body’s stress response. Such neuroinflammation does it’s damage by injuring brain cells, disrupting communication between brain cells and impairing neuroplasticity, the capacity of the brain to perform self-repair. 25

Decline in neuroplasticity, disrupted brain cell communication and tissue damage—the fallout of inflammation—may be the real driver of depression biology. The changes in tryptophan levels may be simply a marker of depression—the consequences of raging inflammation driven by stress and inflammatory lifestyle factors.

Inflammation and its cascade of biochemical consequences might be the reason that SSRI antidepressant medications that boost serotonin levels in the brain don’t work in patients with high levels of inflammation. 26 And it might also explain why patients that have elevated inflammation may not respond that well to psychotherapy. 27, 28

High levels of inflammation may also explain the strong association between depression and cardiovascular disease 29 since inflammation is a known trigger of the latter. It might also account for why reduced tryptophan intake does not seem to worsen depressive symptoms in people with untreated depression. 30

If inflammation is the driver of depression, stress steps on the gas pedal.

Stress & Inflammation Frustrate Depression Recovery

Stress and inflammation in people experiencing long bouts of depression has been found to cause atrophy in brain regions that are responsible for mood regulation31 including shrinkage of the hippocampus. 32 The atrophy is potentially reversible upon recovery from depression.

Atrophy is also seen in the prefrontal cortex of depressed patients. Stress-induced damage and decreases in the regenerative capacity “could be relevant to hippocampal atrophy,” according Robert M. Sapolsky, a distinguished professor of neurobiology at the Stanford University School of Medicine. 33

Stress sinks levels of a salutary substance called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which heals neurons in the brain and promotes neuroplasticity. Such changes in BDNF are implicated in the development of depression. 34, 35 The decline in BDNF seen in depression is a marker of the condition in a similar way that spiking temperature is a marker of influenza or elevated blood sugar a marker of diabetes. This interference in the brain’s regenerative capacity—its neuroplasticity—is yet another plague unleashed from Pandora’s box by out-of-control inflammation.

When stress sparks inflammation, inflammatory substances leak between brain neurons throwing a monkey wrench into the brain’s neural circuitry at the same time as stress is significantly decreasing BDNF. That lost BDNF could have helped restore the damage done to neuroplasticity. 36, 37, 38 This is especially problematic when one considers that stress-induced inflammation can also lead to cellular damage and an attack on brain structures like the hippocampus.

Stress may have another way to work its mischief on an inflammation-battered brain.

Brains & Bellies Talk to Each Other

The burgeoning evidence supports a link between psychological stress and the billions of bacteria that colonize our GI tracts, the microbiota. The microbiota is part of the gut-brain axis—a two-way biochemical conversation between our brains and bellies that has a pivotal role in mental and physical health. The gut-brain axis is the link between what we call “gut-feelings” and the emotions registered by our mind.

There’s research linking the balance of various bacterial species inhabiting our gut to our psychological health via its effect on the gut-brain axis. 39 Changes in the composition of the microbes that colonize the GI tract have been implicated in triggering or maintaining states like depression and anxiety.40, 41, 42, 43, 44 Some researchers unequivocally assert disturbances in the balance of gut bugs can cause depression and has a role in its cure. 45

The evidence that a disrupted “microbiota-gut-brain axis” is a cause of depression is so strong that it is a hot target for development of new antidepressants. 46

There is evidence that suggests that recovery of a dysregulated gut microbiota goes hand in hand with recovery from depression. When one gets better, the other does too. 47, 48, 49, 50

Stress not only disrupts the biology of the brain, but also the biology of the gut.

“Our findings provide evidence that psychological stress is associated with changes in the abundance of the gut microbiota,” was the conclusion of researchers who conducted a 2023 study, a systematic review of 13 studies that included participants with major depressive disorder. 51

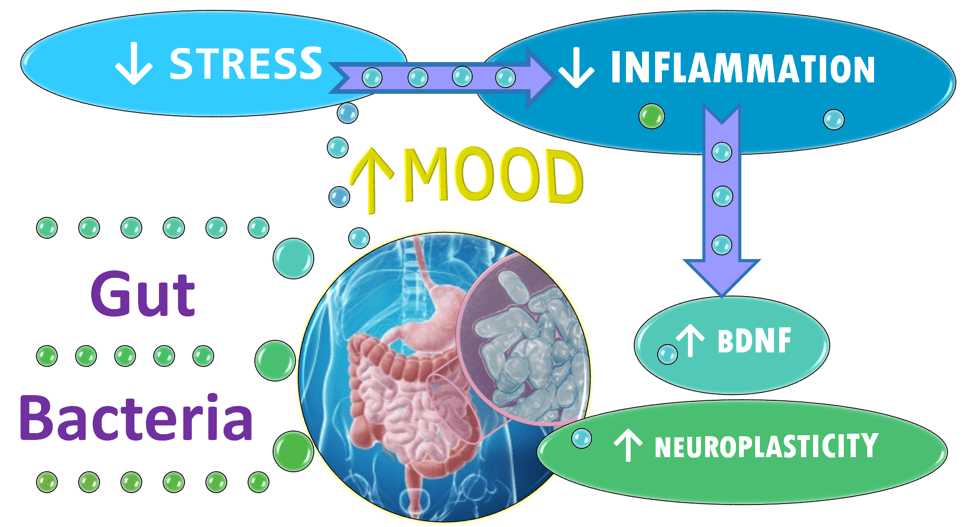

Changes in the balance of GI bacteria appear to affect a wide range of factors that can play a role in depression and anxiety including serotonin release. The microbiota also help regulate levels of systemic inflammation. The gut bacteria alter levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which promotes the growth of new neurons and new connections between brain cells. The microbiota also impacts the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—the fight-or-flight machinery the body uses to respond to stressors and threats. 52, 53

If the bacteria in the gut—the microbiota—are compromised or altered as is seen to occur in depression, 54, 55, 56, 57 it also impacts the absorption and availability of tryptophan and how much serotonin is manufactured both in the gut and in the brain.

Even if low tryptophan or low serotonin don’t cause depression, dietary tryptophan plays a pivotal role in the gut-brain axis—the two-way communication system—where stressful thinking can alter gut bacteria and gut bacteria can affect how our bodies react to stress.

Scientists are now investigating how the way we absorb and metabolize dietary tryptophan as an important driver of the connection between the health of our gut and that of our mind. 58 Tryptophan is one of the ways that the gut talks to the brain and vice versa. An example of how this communication network works is the way gut bacteria can shift tryptophan metabolism from neuroprotective metabolites to neurotoxic ones thereby conveying a potentially depressing message to the brain. 59 This shift in the relative balance of neuroprotective versus neurotoxic tryptophan metabolites has been implicated in psychiatric disorders like depression and anxiety.60, 61

How we deal with stress not only affects how tryptophan influences the brain it also affects the bacteria that live in our gut, which in turn talk back to the brain. It’s amazing to realize that scientists are now capable of transferring the psychological state of one individual into an animal through the bacteria that live in our gut.

In a 2016 study titled “Transferring the Blues,” researchers transplanted gut bacteria obtained from patients with depression into the GI tracks of mice without pathogenic bacteria resulting in depressive-like behaviors in the mice that received gut bug transplants from depressed humans. 62

Researchers also found that a probiotic supplement containing live bacteria, decreased production of inflammatory proteins and increased circulating levels of tryptophan and concentrations of a neuroprotective tryptophan metabolite in animal recipients. 63

It may that improved microbiota leads to improved mood because of biochemical factors including a reduction of inflammation, ramping down fight-or-flight physiology, reducing neurotoxic tryptophan metabolites as well as increasing neuroplasticity.

Given that stress may be at the heart of what drives depression with tryptophan depletion being a consequence, it should come as no surprise that stress-busting techniques are a much more impactful way to defeat depression while tryptophan supplementation is not.

Stress-Busting Techniques

People are all unique when it comes to the wide array of stress-busters. Different techniques work better for some people than others. But stress reduction doesn’t take as much time as one might think. Just participating in eight sessions of stress management training might reduce anxiety and depression. 64

The value of reducing stress is widely embraced. A meta-analytic review of 39 studies including 1,140 for a range of conditions including generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and other psychiatric or medical conditions found that mindfulness-based therapy, a widely-used stress-busting technique, was associated with significant improvement in anxiety disorders and depression. 65 One such technique, Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy, reduces the risk of relapsing into depression after finishing treatment by about 22% when compared to people receiving antidepressants. 66 Link to more on Mindfulness

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is the gold-standard, talk therapy technique that has proven efficacy in the treatment of depression. Researchers believe that CBT helps people with depression ramp down overactive threat centers in the brain responsible for triggering the body’s stress response. To find out more about how CBT is thought to lower stress click link: Talk Therapy

Hypnotherapy is another talk therapy technique that can lower stress by lowering levels of the stress-hormone cortisol. 67, 68 Hypnotherapy delivered over 6 months is at least as effective as CBT for reducing symptoms of depression. 69 Link to more on Hypnotherapy

If stress is the culprit, biofeedback might be a cure.

Frequent biofeedback sessions lasting only six minutes were associated with lower stress levels, a small 2023 study found. The researchers used biofeedback to lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol, a marker of stress. Researchers conducting this study measured cortisol levels in young female athletes who did short sessions of heart rate variability biofeedback lasting six minutes, three times a day for seven weeks. Mid-day cortisol levels decreased significantly after biofeedback sessions, the study found. In all sessions except two, cortisol levels decreased significantly during all biofeedback sessions in which levels were measured. Researchers concluded that HRV biofeedback is an effective method to control stress in female athletes. 70

Biofeedback is a mind-body therapy that has the ability to reveal changes in stress levels by using advanced instruments to display fluctuations in body systems that are activated by stress. Awareness of elevated stress levels can guide a skillful clinician to facilitate the shift to more relaxed states.

Biofeedback also facilitates states of heightened sensory awareness that enhance the efficacy of mindfulness-based talk therapies for anxiety and depression. The American Psychological Association gives a brief explanation of biofeedback

There are a number of studies demonstrating biofeedback’s effectiveness in treating a variety of mental health conditions.

A 2022 study found that depressive thinking resulted in changes in heart rate and perspiration during times of elevated stress. After biofeedback training, levels of stress, anxiety, and depressive thinking fell while heart rate patterns consistent with relaxation rose. There were no such changes in the people in the control group. 71

A type of biofeedback called heart rate variability biofeedback, improves depressive symptoms, a 2021 analysis of 14 randomized controlled studies including 794 participants concluded. The researchers wrote that it “should be considered as a valid technique to increase psychological well-being.” 72

Many universities offer biofeedback in campus counseling and mental health centers and some offer biofeedback directly to patients in the larger community. In these clinics, student clinicians in medical or counseling degree programs are overseen by licensed providers. Typically, it is the students who provide biofeedback services to those seeking care. Examples include:

- Vassar Counseling Services

- Vanderbilt University Biofeedback

- Georgetown University

- Loyola Medical School

- University of California Berkeley University Health Services

- University of Akron Counseling Center

- Washington State University Cougar Health Services

- San Diego State University Counseling & Psychological Services

- University of New Hampshire Health & Wellness Services

- Iowa State University, Student Counseling Services

- University of Florida Health, College of Medicine, Mental Health Crisis Support

There are a number of licensed private counselors and physicians who offer biofeedback. A small number of them hold certifications in biofeedback. Biofeedback certification requirements for current applicants span a broad array of knowledge in the anatomy and physiology of human stress as well as the science of biofeedback and include contact hours demonstrating competency in hands-on biofeedback skills in each of the five basic biofeedback modalities as well as passage of a rigorous board examination.

Mood Change Medicine’s Dr. Meissner is board certified in biofeedback.

To find out how biofeedback helps defeat stress and depression, click link below:

Links to more information about tryptophan:

Tryptophan & Its Alternatives for Depression, Anxiety & Sleep

Are Tryptophan Supplements Effective Insomnia?

Tryptophan for Sleep: Not as Simple as Popping a Pill

Are Tryptophan Supplements Effective for Anxiety & Depression?

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Bell C, Abrams J, Nutt D. “Tryptophan depletion and its implications for psychiatry.” Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:399-405.. View abstract. ↩︎

- Murphy FC, Smith KA, Cowen PJ, et al. “The effects of tryptophan depletion on cognitive and affective processing in healthy volunteers.” Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:42-53.. View abstract ↩︎

- Bell C, Abrams J, Nutt D. “Tryptophan depletion and its implications for psychiatry.” Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:399-405.. View abstract. ↩︎

- Murphy FC, Smith KA, Cowen PJ, et al. “The effects of tryptophan depletion on cognitive and affective processing in healthy volunteers.” Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:42-53.. View abstract ↩︎

- Coppen A, Eccleston EG, Peet M. Total and Free tryptophan concentration in the plasma of depressive patients. Lancet. 1973 Jul 14;2(7820):60-3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)93259-5. PMID: 4123618. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Parry-Billings M, Newsholme EA. Decreased plasma tryptophan levels in major depression Decreased plasma tryptophan levels in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1989 Jan-Feb;16(1):27-31. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(89)90051-7. PMID: 2521647. ↩︎

- Coppen A, Eccleston EG, Peet M. Total and Free tryptophan concentration in the plasma of depressive patients. Lancet. 1973 Jul 14;2(7820):60-3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)93259-5. PMID: 4123618. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964 ↩︎

- Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence.” 2023. Mol Psychiatry. 28, 3243–3256 (2023). doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0 (nature.com) ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964 ↩︎

- Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence.” 2023. Mol Psychiatry. 28, 3243–3256 (2023). doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0 (nature.com) ↩︎

- Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence.” 2023. Mol Psychiatry. 28, 3243–3256 (2023). doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0 (nature.com) ↩︎

- Hideki Miura, Norio Ozaki, Makoto Sawada, Kenichi Isobe, Tatsuro Ohta & Toshiharu Nagatsu “A link between stress and depression: Shifts in the balance between the kynurenine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depression.” Stress. (2008) 11:3, 198-209, DOI: 10.1080/10253890701754068 tandfonline ↩︎

- Hideki Miura, Norio Ozaki, Makoto Sawada, Kenichi Isobe, Tatsuro Ohta & Toshiharu Nagatsu “A link between stress and depression: Shifts in the balance between the kynurenine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depression.” Stress. (2008) 11:3, 198-209, DOI: 10.1080/10253890701754068 tandfonline ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Kan Gao, Chun-long Mu, Aitak Farzi, Wei-yun Zhu. “Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain.” Advances in Nutrition. 2020. Volume 11, Issue 3, 2020, Pages 709-723, ISSN 2161-8313, doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127. (sciencedirect) ↩︎

- Kan Gao, Chun-long Mu, Aitak Farzi, Wei-yun Zhu. “Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain.” Advances in Nutrition. 2020. Volume 11, Issue 3, 2020, Pages 709-723, ISSN 2161-8313, doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127. (sciencedirect) ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964 ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964 ↩︎

- O’Farrell K, Harkin A. “Stress-related regulation of the kynurenine pathway: relevance to neuropsychiatric and degenerative disorders.” Neuropharmacology. 2017. 112 (Pt B) (2017), pp. 307-323 sciencedirect ↩︎

- Kan Gao, Chun-long Mu, Aitak Farzi, Wei-yun Zhu. “Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain.” Advances in Nutrition. 2020 Volume 11, Issue 3, 2020, Pages 709-723, ISSN 2161-8313, doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127. (sciencedirect.com) ↩︎

- O’Farrell K, Harkin A. “Stress-related regulation of the kynurenine pathway: relevance to neuropsychiatric and degenerative disorders.” Neuropharmacology. 2017. 112 (Pt B) (2017), pp. 307-323 sciencedirect ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Lopresti AL. “Cognitive behaviour therapy and inflammation: A systematic review of its relationship and the potential implications for the treatment of depression.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;51(6):565-582. doi:10.1177/0004867417701996 ↩︎

- Strawbridge R, Marwood L, King S, et al. “Inflammatory Proteins and Clinical Response to Psychological Therapy in Patients with Depression: An Exploratory Study.” J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 2;9(12):3918. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123918. PMID: 33276697; PMCID: PMC7761611. ↩︎

- Shen R, Zhao N, Wang J, Guo P, Shen S, Liu D, Zou T. “Association between level of depression and coronary heart disease, stroke risk and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: Data from the 2005-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.” Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Oct 26;9:954563. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.954563. PMID: 36386369; PMCID: PMC9643716. ↩︎

- Delgado PL, Price LH, Miller HL. “Serotonin and the neurobiology of depression. Effects of tryptophan depletion in drug-free depressed patients.” Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1994;51:865-74. View abstract. ↩︎

- Capuco A., Urits I., Hasoon J., Chun R., Gerald B., Wang J. K., et al. “Current perspectives on gut microbiota dysbiosis and depression.” Adv. Ther. 2020. 37, 1328–1346. 10.1007/s12325-020-01272-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021 ↩︎

- Robert M. Sapolsky. “Depression, antidepressants, and the shrinking hippocampus.” National Academy of Sciences. October 23, 2001 pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.231475998. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021 ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Martin CR, Osadchiy V, Kalani A, Mayer EA. “The brain-gut-microbiota axis.” Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. 6 (2) (2018), pp. 133-148 ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023. Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910 ↩︎

- Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, Wang W, Tang W, Tan Z, Shi J, et al. “Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder.” Brain Behav Immun. 2015. 48 (2015), pp. 186-194 ↩︎

- Clarke G, Grenham S, Scully P, Fitzgerald P, Moloney RD, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “The microbiota-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner.” Mol Psychiatry. 2013.18 (6) (2013), pp. 666-673 ↩︎

- Kelly JR, Borre Y, Ciaran OB, Patterson E, El Aidy S, Deane J, Kennedy PJ, Beers S, Scott K, Moloney G, et al. “Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat.” J Psychiatr Res. 2016. 82 (2016), pp. 109-118. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]. ↩︎

- Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Traplin A, O’Sullivan O, Crispie F, Moloney RD, Cotter PD, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “Gut microbiota depletion from early adolescence in mice: implications for brain and behaviour.” Brain Behav Immun. 2015. 48 (2015), pp. 165-173 ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023. Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910 ↩︎

- Chang L., Wei Y., Hashimoto K. “Brain-gut-microbiota axis in depression: a historical overview and future directions.” Brain Res. Bull. (2022). 182, 44–56. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.02.004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Qu Y., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., Dong C., Hashimoto K. “Comparison of (R)-ketamine and lanicemine on depression-like phenotype and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in a social defeat stress model.” Sci. Rep. (2017). 7, 15725. 10.1038/s41598-017-16060-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Yang C., Qu Y., Fujita Y., Ren Q., Ma M., Dong C., et al. “Possible role of the gut microbiota-brain axis in the antidepressant effects of (R)-ketamine in a social defeat stress model.” Transl. Psychiatry. (2017). 7, 1294. 10.1038/s41398-017-0031-4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023. Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910. ↩︎

- Lu Ma, Yating Yan, Richard James Webb, Ying Li, Sanaz Mehrabani, Bao Xin, Xiaomin Sun, Youfa Wang, Mohsen Mazidi; “Psychological Stress and Gut Microbiota Composition: A Systematic Review of Human Studies.” Neuropsychobiology. 2023. 6 October 2023; 82 (5): 247–262. doi.org/10.1159/000533131 ↩︎

- Du Y., Gao X.R., Peng L., Ge J.F. Crosstalk between the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Depression. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04097. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562 ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023 Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36871910 ↩︎

- Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression?” Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013 Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre. Sep;25(9):713-9. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12198. PMID: 23910373 ↩︎

- Bastiaanssen T. F. S., Cussotto S., Claesson M. J., Clarke G., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. “Gutted! Unraveling the Role of the Microbiome in Major Depressive Disorder.” Harvard Rev. Psychiatry. 2020. 28, 26–39. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000243 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Cheung S. G., Goldenthal A. R., Uhlemann A. C., Mann J. J., Miller J. M., Sublette M. E. “Systematic Review of Gut Microbiota and Major Depression.” Front. Psychiatry. (2019). 10, 34. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00034 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Kan Gao, Chun-long Mu, Aitak Farzi, Wei-yun Zhu. “Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain.” Advances in Nutrition. 2020. Vol. 11, Issue 3, 2020, Pages 709-723, ISSN 2161-8313, doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127. (sciencedirect.com ) ↩︎

- Kan Gao, Chun-long Mu, Aitak Farzi, Wei-yun Zhu. “Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain.” Advances in Nutrition. 2020 Volume 11, Issue 3, 2020, Pages 709-723, ISSN 2161-8313, doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127. (sciencedirect.com) ↩︎

- O’Farrell K, Harkin A. “Stress-related regulation of the kynurenine pathway: relevance to neuropsychiatric and degenerative disorders.” Neuropharmacology. 2017. 112 (Pt B) (2017), pp. 307-323 sciencedirect ↩︎

- Kan Gao, Chun-long Mu, Aitak Farzi, Wei-yun Zhu. “Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain.” Advances in Nutrition. 2020 Volume 11, Issue 3, 2020, Pages 709-723, ISSN 2161-8313, doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127. (sciencedirect.com) ↩︎

- Kelly JR, Borre Y, Ciaran OB, Patterson E, El Aidy S, Deane J, Kennedy PJ, Beers S, Scott K, Moloney G, et al. “Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat.” J Psychiatr Res. 2016. 82 (2016), pp. 109-118. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Bienenstock J, Dinan TG. “The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: an assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2008. 43 (2) (2008), pp. 164-174 ↩︎

- Yazdani M, Rezaei S, Pahlavanzadeh S. “The effectiveness of stress management training program on depression, anxiety and stress of the nursing students.” Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2010 Fall;15(4):208-15. PMID: 22049282; PMCID: PMC 3203278. ↩︎

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. “The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review.” J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010 Apr;78(2):169-83. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. PMID: 20350028; PMCID: PMC 2848393. ↩︎

- Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, et al. “Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: An individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials.” JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(6):565-74. View abstract. ↩︎

- Hamzah, F., Mat, K. C., & Amaran, S. (2021). “The effect of hypnotherapy on exam anxiety among nursing students.” Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, 19(1), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2020-0388 PubMed Google Scholar ↩︎

- Rizkiani, I., Respati, S. H., Sulistyowati, S., Budihastuti, U. R., & Prasetya, H. “The Effect of Hypnotherapy on Serum Cortisol Levels in Post-Cesarean Patients.” Journal of Maternal and Child Health. (2021). 6(3), 258–266. Retrieved from thejmch.com/index.php/thejmch/article/view/587 ↩︎

- Fuhr K, Meisner C, Broch A, et al. “Efficacy of hypnotherapy compared to cognitive behavioral therapy for mild to moderate depression – Results of a randomized controlled rater-blind clinical trial.” J Affect Disord. 2021;286:166-173. View abstract. ↩︎

- Makaracı Y, Makaracı M, Zorba E, Lautenbach F. “A Pilot Study of the Biofeedback Training to Reduce Salivary Cortisol Level and Improve Mental Health in Highly-Trained Female Athletes.” Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2023 Sep;48(3):357-367. doi: 10.1007/s10484-023-09589-z. Epub 2023 May 19. PMID: 37204539. 37204539 ↩︎

- Schumann A, Helbing N, Rieger K, Suttkus S, Bär KJ. “Depressive rumination and heart rate variability: A pilot study on the effect of biofeedback on rumination and its physiological concomitants.” Front Psychiatry. 2022. Aug 25;13:961294. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.961294. PMID: 36090366; PMCID: PMC9452722. 36090366 ↩︎

- Pizzoli SFM, Marzorati C, Gatti D, Monzani D, Mazzocco K, Pravettoni G. “A meta-analysis on heart rate variability biofeedback and depressive symptoms.” Sci Rep. 2021. Mar 23;11(1):6650. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86149-7. PMID: 33758260; PMCID: PMC7988005 ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.