By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

June 2, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

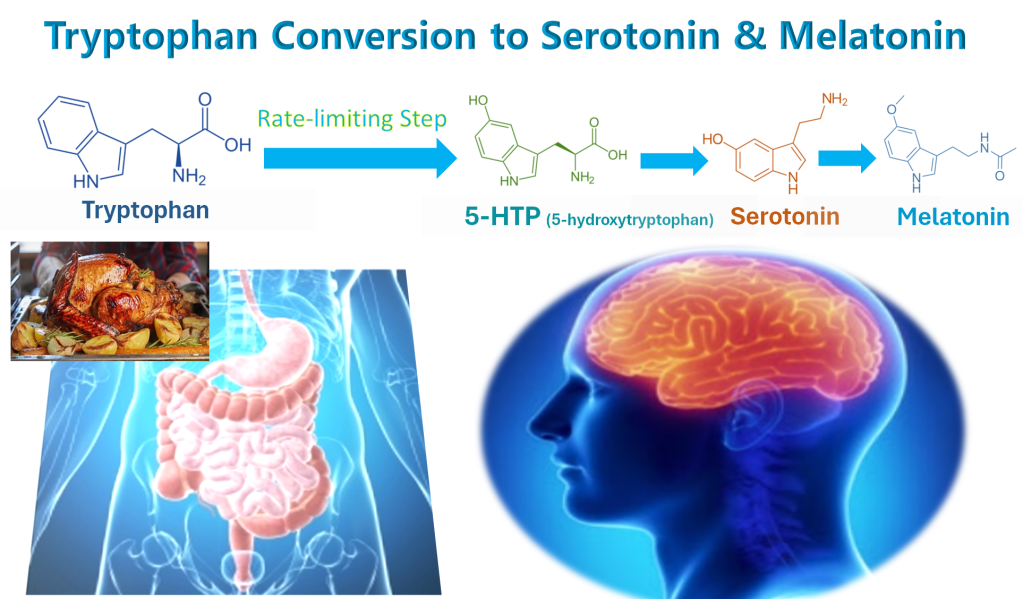

The pathway that our bodies use to turn the amino acid tryptophan obtained from food into the mood-hormone serotonin runs right through 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan).

Tryptophan from foods is converted to 5-HTP. 5-HTP is converted to 5-HT (5-hydroxytryptamine), which is another name for serotonin. Serotonin is then converted into the sleep-hormone melatonin.

Serotonin has wide-ranging effects on many body systems. Serotonin plays a role in sleep, feelings of satiety, hunger, physical pain, and blood pressure. It helps regulate a host of mental and physical functions including perception, attention, memory, reward, anger and aggression behavior, sexuality, and body temperature. 1, 2 But, it is most well known for its effects on mood including anxiety as well as depression.

Much of the thinking about what’s responsible for 5-HTP’s antidepressant effects centers around its capacity to boost levels of the hormone serotonin. Boosting serotonin levels and/or serotonin activity is what has been thought to relieve depression symptoms in people taking selective-serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) antidepressant medications.

Why can’t we just eat tryptophan-rich foods?

This raises the question of why doesn’t eating tryptophan-rich foods boost serotonin levels as much as taking 5-HTP supplements?

This question was partially answered in the article “Tryptophan for Sleep: Not as Simple as Popping a Pill”. In a nutshell, there are more ways for tryptophan to get made into other biochemicals besides serotonin than there are for 5-HTP.

And there are many ways that tryptophan levels in the brain may be lowered by other nutrients we eat. And there are many possible nutrient deficiencies that could defeat the conversion from tryptophan into 5-HTP. But there’s another key reason that we can’t simply eat more tryptophan to attain the same serotonin boost that can be had from taking 5-HTP.

The tryptophan pathway that turns tryptophan into serotonin and then melatonin hits a bottleneck at the point where tryptophan converts into 5-HTP. 3 The step in any biochemical pathway where it takes more time to convert one biochemical into the next one in that pathway—the bottleneck step—is called the rate-limiting step in that pathway.

Taking 5-HTP instead of tryptophan bypasses this bottleneck, thus 5-HTP more effectively boosts brain levels of serotonin and the melatonin that is made from it.

Another question that arises is why don’t we just take serotonin and bypass all the slow biochemistry? Why not skip the middle-men?

Why can’t we just take serotonin tablets?

For one thing, serotonin from a pill cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. But more importantly, taking serotonin is far too dangerous and could end up killing us before it causes any improvement in depression symptoms. That’s why there are really no serotonin supplements or medications in the US market.

This begs a very important question: Does low serotonin cause depression?

Does low serotonin cause depression?

There’s conflicting evidence regarding serotonin being a biological driver of depression. Because serotonin is made from tryptophan in the body, researchers have looked at low serotonin as causing depression by noting that low levels of its precursor (tryptophan) is associated with depression.

For example, a study of a group of depressed women found that they had very significantly reduced plasma levels of free tryptophan and it also found that their tryptophan levels increased significantly after recovery from depression. 4 Healthy people on a low-tryptophan diet may experience depressive symptoms, studies have found. 5, 6 Other studies have found that depressed persons have decreased blood levels of tryptophan. 7, 8

But in the article “Low Tryptophan = Low Serotonin. Does Low Serotonin = Depression?” it becomes clear that pinning the blame on low serotonin levels as the biological cause of depression is not a done deal. There’s quite a bit of evidence to the contrary.9 (See article for details.) The article points out some of the possible ways that tryptophan may play role in depression separate from its impact on serotonin. The reduced tryptophan levels seen in depression could be the fallout of these other biochemical processes. Declining tryptophan, and any resultant decline in serotonin, could be a consequence rather than a cause of depression.

Given that the other tryptophan-related factors play a role in the biology of depression, it makes it more difficult to isolate serotonin as a possible cause of depression, independent of what’s happening with tryptophan. Just because 5-HTP can boost serotonin, it doesn’t rule out other causes for its antidepressant effects and it still doesn’t answer the question—does raising serotonin or increasing its activity cure or improve depression? SSRI antidepressants also boost serotonin, that doesn’t mean that’s how they work either.

But before we can answer how or why antidepressants work, we want to know if they indeed do work.

Because serotonin is so integral to so many body systems, it’s understandable that SSRI antidepressants—which boost serotonin—can cause a number of side-effects impacting many body systems.

People often look to supplements to avoid the side effects of pharmaceuticals like Prozac, Lexapro, Zoloft etc. The article: “Are Tryptophan Supplements Effective for Anxiety & Depression?” discusses that though tryptophan plays a pivotal role in mood, current scientific evidence does not support the efficacy of tryptophan supplements for depression or anxiety.

A closer examination of the evidence for 5-HTP’s efficacy in depression also gets us into murky waters.

Is 5-HTP an effective antidepressant?

Positive results from early studies 10 that largely lacked scientific rigor showed benefits of 5-HTP for depression and other conditions. This spurred the supplement’s popularity.

A 1977 double-blind study found that 5-HTP was as effective as a then commonly-prescribed antidepressant in patients taking a powerful Parkinson’s disease drug. 11

This provided some support for 5-HTP being as effective as antidepressant medications for depression in people with Parkinson’s also taking the Parkinson’s drug. But it leaves open the question as to whether it is effective in people without Parkinson’s disease who are not on that drug. And it also doesn’t answer the bigger question about the effectiveness of the tricyclic antidepressant medication, imipramine, that was used in the study?

By 2002 some researchers raised doubts about the solidity of the evidence showing the benefits of 5-HTP for depression.

A systematic review that examined 106 studies from 1966 to 2000 chose to include only two studies in their analysis, one study on 5-HTP and one on its precursor tryptophan. The review concluded that all the other studies lacked the scientific rigor necessary to consider their results valid. The two included studies suggested that “5-HTP and L-tryptophan are better than placebo at alleviating depression.”12

The 5-HTP flame was not rekindled until in 2012, when a randomized, double-blind study found 5-HTP to be as effective as the SSRI antidepressant Prozac (fluoxetine) in patients having their first depressive episode. The antidepressant effects were seen in mild, moderate and severe depression. The researchers concluded that “The therapeutic efficacy of l-5-HTP was considered as equal to that of fluoxetine.” 13

But the otherwise rigorous 2012 study suffered from a failure to compare 5-HTP to a placebo (an inert pill). 14 However, some argue that Prozac itself is not actually shown to be effective for depression. If true, this would call into question whether the results of this study prove 5-HTP to be effective for depression.

A 2020 systematic review of 13 clinical studies showed that 5-HTP taken for up to 8 weeks improved symptoms of depression in almost two thirds of patients. There was a 65% remission rate based on the pooled results of the studies. Seven of the 13 studies found large improvement in depressive symptoms. “The findings of this meta-analysis revealed a positive effect of 5-HTP supplementation on depression,” the researchers concluded. But they added that many studies used methodology that was “of relatively low quality” mainly because they didn’t compare 5-HTP to placebos (inert pills). 15

This makes it hard to rule out the placebo effect. The placebo effect is a beneficial effect produced by a bogus pill that is inert such as a sugar pill that doesn’t contain any active medication. The benefits are not due to the sugar pill. Therefore, the benefits must be due to the patient’s belief in that treatment.

A task force composed of 31 leading academics and clinicians from 15 countries chose not to recommend 5-HTP in their guidelines as a stand-alone or supportive treatment for unipolar depression citing “methodologically weak underlying data.” The task force noted that 5-HTP “may benefit symptomatic improvement of insomnia” in patients who are depressed. 16

This adds another question to a growing number of questions about the effectiveness of 5-HTP, namely, if 5-HTP improves sleep maybe its benefits are not due to serotonin but to improved sleep. But we don’t have enough studies to determine if 5-HTP improves sleep.

The National Library of Medicine database MedlinePlus called 5-HTP “possibly effective” for depression and concluded that: “Taking 5-HTP by mouth seems to improve symptoms of depression in some people. It might work as well as some prescription antidepressant drugs.”

It would help shore up the evidence for 5-HTP’s efficacy if there was resolution to the question about whether or not SSRI antidepressants—the drugs like Prozac that boost serotonin activity—are effective for depression.

Are SSRIs effective antidepressants?

In regards to 5-HTP being as effective as an SSRI anti-depressant, some researchers say that’s not necessarily saying much since SSRIs often don’t work very well. One study showed that more than two of every three patients taking an SSRI do not get a remission from depression. And less than half of patients get any beneficial response at all to the SSRI. 17 That’s why physicians frequently try one SSRI after another in hopes of finding one that will work.

Another study found that only 22% of chronically depressed patients experience remission of depression from another type serotonin-modulating antidepressant called a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI). 18

Harvard Medical School researcher Irving Kirsch—in seeking to answer the question of whether the SSRI anti-depressants such as Zoloft and Prozac are effective—analyzed published research data as well as unpublished drug company data obtained from the federal Food and Drug Administration. “Most (if not all) of the benefits are due to the placebo effect,” Kirsch wrote. 19

The small benefit of SSRIs found in some studies over and above placebo controls can be explained by study subjects learning that that they were taking the real drug and not a placebo, according to Kirsch. And he pointed out that any small benefit is so tiny that it would not make a recognizable difference in the outcome of depression treatment, when judged by the United Kingdom’s National Health Service treatment efficacy criterion. 20

Kirsch and other researchers independently reviewed SSRI drug trial data and found that well under half showed statistically significant benefits of SSRI drugs over inert placebo. 21, 22 The review included an FDA study on the clinical trials of all antidepressants that the agency had approved between 1983 and 2008.” 23, 24

Kirsch’s data analyses show that “the placebo response was 82% of the response to these antidepressants.” 25 The results were confirmed with a replication study including a larger number of clinical trials. 26

So, it appears that both 5-HTP and SSRI pharmaceutical antidepressants are on shaky ground. Which adds more mud to already muddy waters regarding low serotonin as the biological trigger of depression.

In studies using animals as subjects, the placebo effect is not in play.

If not serotonin, why might antidepressants work?

Researchers from diverse fields of study including endocrinology, microbiology and pharmacology trying to answer the question of how 5-HTP works have turned their attention to how 5-HTP affects the “microbiota-gut-brain axis.” 27 Billions of bacteria composed of some 40,000 bacterial species have evolved together with humans to live in our GI tract in an intricate ecosystem called the “gut microbiota.”

The gut-brain axis is a two-way biochemical conversation between our brains and bellies that plays a crucial role in our mental and physical health. Some researchers unequivocally assert disturbances in the balance of gut bugs can cause depression and has a role in its cure. 28

The evidence that the “microbiota-gut-brain axis” is a cause of depression is so strong that it is a hot target for development of new antidepressants. 29

Certain types of gut bugs might promote depression. In a 2016 study titled “Transferring the Blues,” researchers transplanted gut bacteria obtained from patients with depression into the GI tracks of mice without pathogenic bacteria resulting in depressive-like behaviors in the mice that received the human gut bug transplants. 30

If mood-deflating microorganisms can cause depression, maybe mood-busting bugs can cure it. And maybe how antidepressants work is via their effects on gut microbiota.

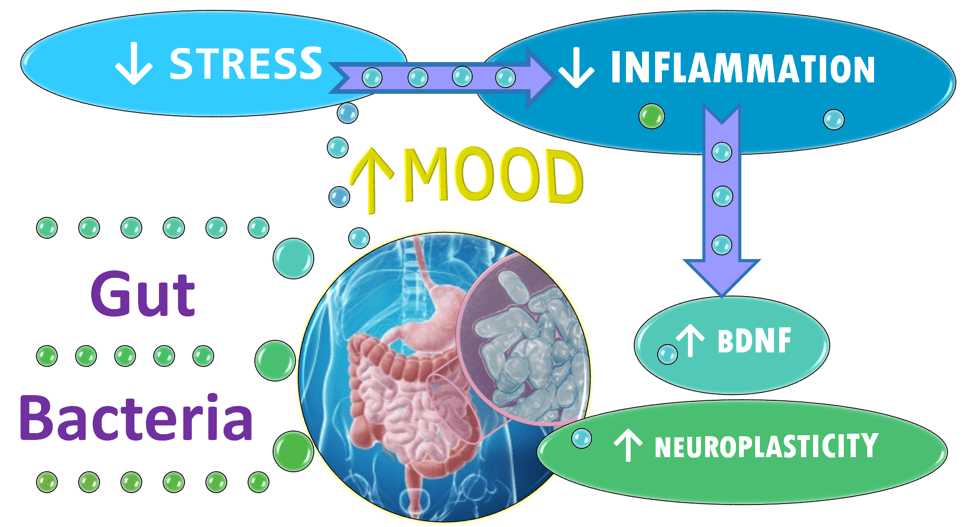

The surprising breakthrough came in a 2022 mouse study. 5-HTP significantly reversed microbiota disturbances in “depressed” mice. The researchers also found that “5-HTP efficiently improves depressive symptoms in mice.” Cure the gut, cure the brain? 31

The researchers caused the depressive symptoms in the mice by making stressful changes in their cages and putting them on a diet heavy with fat. 32

Giving 5-HTP to the stressed mice largely recovered the “diversity and richness of gut microbial communities and relative abundance” of specific bacterial species that had been damaged by the dietary and social stressors. 33

These researchers put another group of mice not given 5-HTP on the same depression-inducing diet and exposed them to the same depression-inducing stressors in their cages to which the 5-HTP mice were exposed. Both groups of stressed mice developed disturbances in their microbiota and depressive behaviors. But unlike the 5-HTP group, the mice not dosed with 5-HTP stayed “depressed.” 34

5-HTP also partially restored concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF) lowered by “depression” in the mice, the researchers said.35 BDNF is believed to play a key role in how the body heals depression in humans.

The results of this study combined with mounting evidence from other studies suggest different ways—beyond serotonin—that 5-HTP may be working to defeat depression. Namely, protections from stress and diet-induced damage to the gut microbiota, cooling stress-induced inflammation and boosting levels of depression-buster BDNF. The article “Gut-Brain Axis: Director of Mental Health?” explains the gut bacteria affects on stress, inflammation, BDNF and more.

BDNF levels are reduced in people with major depressive disorder and increase after the depression remits. 36, 37 Such changes in BDNF are implicated in the development of anxiety and depression via their effects on neuroplasticity of the brain. 38, 39

Neuroplasticity is the ability of the brain to grow, reorganize and recover from stress-induced damage. It is the way that the brain rewires neural networks so that it can perform in ways that differs from how it performed in the past.

Gut bugs play a key role in regulating stress, researchers say. More specifically, the microbiota has two-way communication with the brain through inflammatory chemicals, gut hormones like 5-HTP and their metabolites, and substances made by the gut bugs themselves. 40, 41

Probiotics might protect us from stress by promoting microbiota health. Two researchers at the Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre noted findings that giving two specific species of gut bug in a designer probiotic to human subjects had beneficial psychological effects with a decrease in serum cortisol, the stress hormone. 42 “Probiotics can alter brain regions that control central processing of emotion and sensation,” 43

One 2019 study done in “depressed” mice concluded that a gut bug species used in some commercial probiotics, Bifidobacterium longum, “may prevent the onset of depression from chronic stress.” The study found that this probiotic “alleviated the hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response and accordingly reversed the peripheral inflammation status.” This is another way of saying the mice became less reactive to stressful stimuli and as a result they had less inflammation. 44

“Probiotics may be beneficial in alleviating depressive symptoms,” possibly through modifying inflammation, according to preclinical and clinical studies. 45 Studies found that probiotics have a positive impact on alleviating stress responses, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and cognitive functions in human 46, 47, 48 and animal studies. 49

In addition to helping the mice cope with stress, giving the mood-boosting bacteria increases the levels of serotonin via the bug’s role in 5-HTP synthesis50 . The beneficial bacteria also boosts BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, the substance that promotes neuroplasticity and may help heal depression. 51

Studies show humans with major depression also have a signature gut microbiota. 52, 53, 54, 55 And there’s evidence that probiotics that promote healing of the microbiota seen in depression may help heal the depression. Patients who received probiotics had significantly improved symptoms of depression, a 2023 systematic review of 13 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 786 participants concluded. 56

Do antidepressants restore microbiota seen in depression?

There’s reason to believe that anything that helps depression—not just 5-HTP—is likely to help restore the balance in the gut microbiota too. Maybe serotonin increase is not the main way that treatments used to treat depression might help. Maybe restoration of gut bacteria is what’s helping.

Ketamine—a strong anesthetic with hallucinogenic effects used to treat severely depressed patients who haven’t responded to other drugs—has also been shown to partly restore the disrupted gut microbiota in mice exposed to social stress. 57, 58

SSRIs—when they work to improve depression—also have been shown to alter the gut microbiota. 59

When they heal depression, 5-HTP, SSRIs and ketamine all have profound effects on the gut microbiota. But the benefits of a healthy microbiota can be achieved without taking 5-HTP and any other antidepressant drugs and without their limited efficacy and potentially dangerous side effects.

For example, a study using 8 weeks of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) that integrated the elements of mindfulness-based stress reduction into cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) found that MBCT decreased anxiety and depression, which correlated with positive changes in the gut microbiota. 60

Before getting MBCT treatment, study subjects with high levels of anxiety had markedly decreased gut microbiota diversity compared to healthy control subjects. After MBCT treatment, anxious subjects with improved mindfulness and resilience showed gut microbiota that more closely resembled that of healthy controls, the study found. 61

The researchers concluded that the significantly increased diversity of the gut microbiota following treatment with MBCT added evidence for gut-brain communication, highlighting the promise of focusing on microbiota for mental health. And it does this without all the side-effects of the pharmaceuticals. 62

Improving the diet can help defeat depression and it also can heal the microbiota.

Mice fed a high-fat diet in a 5-HTP study discussed above became “depressed.” The rodents had previously consumed normal feed containing 4% fat that was boosted to 35% fat. 63 The study did not report the type of fat the mice were fed, but other rodent studies have used lard like what can be found in pie crusts, commercial baked goods, cornbread mix and refried beans. 64

In a study comparing the effects of lard fed to “menopausal” rodents versus a diet of fish, the lard was found to increase weight gain and impair blood-sugar regulation. It also triggered serotonin-induced overeating. These effects were counteracted by switching them to a fish diet. Only the lard-eating rodents showed increased depressive behaviors. 65

All this is to say that we don’t know if 5-HTP or other antidepressants work because they boost serotonin or if they work due to another factor—for example because they restore the pathogenic microbiota that is characteristic of depression.

Antidepressants: placebos with a lot of side effects?

If one were to accept that how SSRIs work for depression is not by boosting serotonin but because of the placebo effect, SSRIs would be a “placebo” with a lot of potentially unpleasant side effects. Patients discontinuing long-term SSRI treatment commonly suffer from what is euphemistically called “antidepressant discontinuation syndrome” a fancy name for withdrawal syndrome.

In people who take these SSRIs and SNRIs for six weeks or longer, it was thought that abrupt discontinuation would lead to short-lived withdrawal symptoms—the so-called “antidepressant discontinuation syndrome.” But now it’s believed that the symptoms may not be short-lived and are far from mild.

SSRI and SNRI withdrawal symptoms include insomnia, nausea, imbalance, sensory disturbances, elevation, arousal and more. This withdrawal syndrome reportedly happens in about 20 percent of people. 66, 67

A 2020 article published in American Psychological Association said: “The thinking in the medical community was that patients could wean off these drugs with minor side effects, but anecdotally, many patients have reported troubling mental and physical withdrawal symptoms that last for months or even years.” 68

Ketamine has a higher response rate for reversing depression than SSRIs. But depressive relapse is not uncommon with some ketamine studies showing relapse rates as high as eight of nine patients relapsing after treatment. 69 And unlike 5-HTP and SSRIs, ketamine is addictive. Ketamine is an experimental treatment and long-term safety studies are lacking. 70 But the same is true for 5-HTP.

Ketamine, used as an antidepressant may have unknown, long-term side effects. Long-term users of ketamine for recreational purposes might find that the “special K” leaves them with serious health effects that can include schizophrenia symptoms, memory problems and delusions. 71

5-HTP isn’t addictive, and there’s no withdrawal symptoms but it can have safety risks and side effects. The most common side effects include heartburn, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, drowsiness, sexual problems, and muscle problems, according to MedlinePlus.

There’s a lot of strong evidence that psychotherapies like cognitive behavioral therapy 72 behavioral activation 73, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy 74 and physical exercise 75 provide more enduring benefits than oral antidepressants and they do so without side-effects.

The above information is not a substitute for medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before starting or stopping any medication

To find out how Mood Change Medicine helps people with depression, click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Birdsall TC. “5-Hydroxytryptophan: a clinically-effective serotonin precursor.” Altern Med Rev. 1998 Aug;3(4):271-80. PMID: 9727088. ↩︎

- Berger M, Gray JA, Roth BL. “The expanded biology of serotonin.” Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:355-66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. PMID: 19630576; PMCID: PMC5864293. ↩︎

- Nakamura K, Hasegawa H. “Production and Peripheral Roles of 5-HTP, a Precursor of Serotonin.” Int J Tryptophan Res. 2009;2:37-43. doi: 10.4137/ijtr.s1022. Epub 2009 Mar 30. PMID: 22084581; PMCID: PMC3195225 ↩︎

- Coppen A, Eccleston EG, Peet M. “Total and Free tryptophan concentration in the plasma of depressive patients.” Lancet. 1973 Jul 14;2(7820):60-3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)93259-5. PMID: 4123618. ↩︎

- Bell C, Abrams J, Nutt D. “Tryptophan depletion and its implications for psychiatry.” Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:399-405.. View abstract. ↩︎

- Murphy FC, Smith KA, Cowen PJ, et al. “The effects of tryptophan depletion on cognitive and affective processing in healthy volunteers.” Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:42-53.. View abstract ↩︎

- Coppen A, Eccleston EG, Peet M. “Total and Free tryptophan concentration in the plasma of depressive patients.” Lancet. 1973 Jul 14;2(7820):60-3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)93259-5. PMID: 4123618. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Parry-Billings M, Newsholme EA. “Decreased plasma tryptophan levels in major depression”. J Affect Disord. 1989 Jan-Feb;16(1):27-31. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(89)90051-7. PMID: 2521647 ↩︎

- Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence.” Mol Psychiatry. 2023. 28, 3243–3256 (2023). doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0 (nature.com) ↩︎

- Birdsall TC. “5-Hydroxytryptophan: a clinically-effective serotonin precursor.” Altern Med Rev. 1998 Aug;3(4):271-80. PMID: 9727088. ↩︎

- Angst J, Woggon B, Schoepf J. “The treatment of depression with L-5-hydroxytryptophan versus imipramine. Results of two open and one double-blind study.” Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr (1970). 1977 Oct 11;224(2):175-86. PMID: 336002. ↩︎

- Shaw K, Turner J, Del Mar C. “Are tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptophan effective treatments for depression? A meta-analysis.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002 Aug;36(4):488-91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01046.x. PMID: 12169147. ↩︎

- Jangid P, Malik P, Singh P, Sharma M, Gulia AK “Comparative study of efficacy of l-5-hydroxytryptophan and fluoxetine in patients presenting with first depressive episode.” Asian J Psychiatr. 2013 Feb;6(1):29-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.05.011. Epub 2012 Jul 12. PMID: 23380314 ↩︎

- Jangid P, Malik P, Singh P, Sharma M, Gulia AK “Comparative study of efficacy of l-5-hydroxytryptophan and fluoxetine in patients presenting with first depressive episode.” Asian J Psychiatr. 2013 Feb;6(1):29-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.05.011. Epub 2012 Jul 12. PMID: 23380314 ↩︎

- Javelle F, Lampit A, Bloch W, Häussermann P, Johnson SL, Zimmer P. “Effects of 5-hydroxytryptophan on distinct types of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Nutr Rev. 2020;78(1):77-88. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23:424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- Trivedi M. H., Rush A. J., Wisniewski S. R., Nierenberg A. A., Warden D., Ritz L. “Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice.” Am. J. Psychiatry. (2006). 163, 28–40. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, Arnow B, Dunner DL, Gelenberg AJ, Markowitz JC, et al. “A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression.” N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1462–1470 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar ↩︎

- Kirsch I. “Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect.” Z Psychol. 2014;222(3):128-134. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000176. PMID: 25279271; PMCID: PMC4172306. ↩︎

- Kirsch I. “Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect.” Z Psychol. 2014;222(3):128-134. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000176. PMID: 25279271; PMCID: PMC4172306. ↩︎

- Turner E. H., Matthews A. M., Linardatos E., Tell R. A., & Rosenthal R. “Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy.” New England Journal of Medicine. (2008). 358, 252–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Kirsch I. “Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect.” Z Psychol. 2014;222(3):128-134. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000176. PMID: 25279271; PMCID: PMC4172306. ↩︎

- Khin N. A., Chen Y. F., Yang Y., Yang P., & Laughren T. P. “Exploratory analyses of efficacy data from major depressive disorder trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration in support of new drug applications.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. (2011). 72, 464–472. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Kirsch I. “Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect.” Z Psychol. 2014;222(3):128-134. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000176. PMID: 25279271; PMCID: PMC4172306. ↩︎

- Kirsch I. “Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect.” Z Psychol. 2014;222(3):128-134. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000176. PMID: 25279271; PMCID: PMC4172306. ↩︎

- Kirsch I., Deacon B. J., Huedo-Medina T. B., Scoboria A., Moore T. J., & Johnson B. T. “Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: A meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration.” PLoS Medicine. (2008). 5, e45 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023. Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910 ↩︎

- Chang L., Wei Y., Hashimoto K. “Brain-gut-microbiota axis in depression: a historical overview and future directions.” Brain Res. Bull. (2022). 182, 44–56. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.02.004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Kelly JR, Borre Y, Ciaran OB, Patterson E, El Aidy S, Deane J, Kennedy PJ, Beers S, Scott K, Moloney G, et al. “Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat.” J Psychiatr Res. 2016. 82 (2016), pp. 109-118. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Zelada MI, Garrido V, Liberona A, Jones N, Zúñiga K, Silva H, Nieto RR. “Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) as a Predictor of Treatment Response in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): A Systematic Review.” Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 30;24(19):14810. doi: 10.3390/ijms241914810. PMID: 37834258; PMCID: PMC10572866. ↩︎

- Meng F., Liu J., Dai J., Wu M., Wang W., Liu C., et al. “Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in 5-HT neurons regulates susceptibility to depression-related behaviors induced by subchronic unpredictable stress.” J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020. 126, 55–66. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.05.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Foster J. A., Rinaman L., Cryan J. F. “Stress and the gut-brain axis: regulation by the microbiota.” Neurobiol. Stress. 2017. 7, 124–136. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. “Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression?” Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013. 25, 713–719. 10.1111/nmo.12198 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression?” Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013 Sep;25(9):713-9. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12198. PMID: 23910373. ↩︎

- Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L et al. “Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. “Gastroenterology. 2013; 144: 1394–401.e4. View PubMed Google Scholar ↩︎

- Tian P., Zou R., Song L., Zhang X., Jiang B., Wang G., et al. “Ingestion of Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis strain CCFM687 regulated emotional behavior and the central BDNF pathway in chronic stress-induced depressive mice through reshaping the gut microbiota.” Food Funct. (2019). 10, 7588–7598. 10.1039/C9FO01630A [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Eltokhi Ahmed, Sommer Iris E. “A Reciprocal Link Between Gut Microbiota, Inflammation and Depression: A Place for Probiotics?” Frontiers in Neuroscience.2022. Vol. 162022 DOI=10.3389/fnins.2022.852506 ↩︎

- Akkasheh G., Kashani-Poor Z., Tajabadi-Ebrahimi M., Jafari P., Akbari H., Taghizadeh M., et al. “Clinical and Metabolic Response to Probiotic Administration in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial”. Nutr. (Burbank Los Angeles County Calif.) (2016). 32, 315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.09.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Pinto-Sanchez M. I., Hall G. B., Ghajar K., Nardelli A., Bolino C., Lau J. T., et al. “Probiotic Bifidobacterium Longum NCC3001 Reduces Depression Scores and Alters Brain Activity: A Pilot Study in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome.” Gastroenterology. (2017). 153, 448–459.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Goh K. K., Liu Y. W., Kuo P. H., Chung Y. E., Lu M. L., Chen C. H. “Effect of Probiotics on Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis of Human Studies.” Psychiatry Res. 2019. 282, 112568. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112568 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Liu Q. F., Kim H. M., Lim S., Chung M. J., Lim C. Y., Koo B. S., et al. “Effect of Probiotic Administration on Gut Microbiota and Depressive Behaviors in Mice.” Daru J. Faculty Pharmacy Tehran Univ. Med. 2019). Sci. 28, 181–189. doi: 10.1007/s40199-020-00329-w [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Tian P., Wang G., Zhao J., Zhang H., Chen W. “Bifidobacterium with the role of 5-hydroxytryptophan synthesis regulation alleviates the symptom of depression and related microbiota dysbiosis.” J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019. 66, 43–51. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.01.007 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Tian P., Zou R., Song L., Zhang X., Jiang B., Wang G., et al. “Ingestion of Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis strain CCFM687 regulated emotional behavior and the central BDNF pathway in chronic stress-induced depressive mice through reshaping the gut microbiota.” Food Funct. (2019). 10, 7588–7598. 10.1039/C9FO01630A [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023 Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910 ↩︎

- Dinan TG, Cryan JF. “Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression?” Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013 Sep;25(9):713-9. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12198. PMID: 23910373 Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre. ↩︎

- Cheung S. G., Goldenthal A. R., Uhlemann A. C., Mann J. J., Miller J. M., Sublette M. E. “Systematic Review of Gut Microbiota and Major Depression.” Front. Psychiatry. 2019 10, 34. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00034 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Bastiaanssen T. F. S., Cussotto S., Claesson M. J., Clarke G., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. (2020). “Gutted! Unraveling the Role of the Microbiome in Major Depressive Disorder.” Harvard Rev. Psychiatry. 2020. 28, 26–39. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000243 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Zhang, Q., Chen, B., Zhang, J. et al. “Effect of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics on depression: results from a meta-analysis.” BMC Psychiatry. 2023. 23, 477 (2023). doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04963-x bmcpsychiatry. ↩︎

- Qu Y., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., Dong C., Hashimoto K. “Comparison of (R)-ketamine and lanicemine on depression-like phenotype and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in a social defeat stress model.” Sci. Rep. 2017. 7, 15725. 10.1038/s41598-017-16060-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Yang C., Qu Y., Fujita Y., Ren Q., Ma M., Dong C., et al. “Possible role of the gut microbiota-brain axis in the antidepressant effects of (R)-ketamine in a social defeat stress model. Transl. Psychiatry. (2017). 7, 1294. 10.1038/s41398-017-0031-4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Gao M, Tu H, Liu P, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Jing L, Zhang K. “Association analysis of gut microbiota and efficacy of SSRIs antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder.” J Affect Disord. 2023 Jun 1;330:40-47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.143. Epub 2023 Mar 3. PMID: 36871910. ↩︎

- Wang Z, Liu S, Xu X, Xiao Y, Yang M, Zhao X, Jin C, Hu F, Yang S, Tang B, Song C, Wang T. “Gut Microbiota Associated With Effectiveness And Responsiveness to Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Improving Trait Anxiety.” Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Feb 24;12:719829. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.719829. PMID: 35281444; PMCID: PMC8908961. ↩︎

- Wang Z, Liu S, Xu X, Xiao Y, Yang M, Zhao X, Jin C, Hu F, Yang S, Tang B, Song C, Wang T. “Gut Microbiota Associated With Effectiveness And Responsiveness to Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Improving Trait Anxiety.” Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Feb 24;12:719829. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.719829. PMID: 35281444; PMCID: PMC8908961. ↩︎

- Wang Z, Liu S, Xu X, Xiao Y, Yang M, Zhao X, Jin C, Hu F, Yang S, Tang B, Song C, Wang T. “Gut Microbiota Associated With Effectiveness And Responsiveness to Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Improving Trait Anxiety.” Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Feb 24;12:719829. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.719829. PMID: 35281444; PMCID: PMC8908961. ↩︎

- Wu L, Ran L, Wu Y, Liang M, Zeng J, Ke F, Wang F, Yang J, Lao X, Liu L, Wang Q, Gao X. “Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression.” Front Microbiol. 2022. Apr 28;13:864571. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864571. PMID: 35572711; PMCID: PMC9096562. ↩︎

- Boldarine VT, Pedroso AP, Neto NIP, Dornellas APS, Nascimento CMO, Oyama LM, Ribeiro EB. “High-fat diet intake induces depressive-like behavior in ovariectomized rats.” Sci Rep. 2019 Jul 22;9(1):10551. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47152-1. PMID: 31332243; PMCID: PMC6646372. ↩︎

- Dornellas APS, Boldarine VT, Pedroso AP, Carvalho LOT, de Andrade IS, Vulcani-Freitas TM, Dos Santos CCC, do Nascimento CMDPO, Oyama LM, Ribeiro EB. “High-Fat Feeding Improves Anxiety-Type Behavior Induced by Ovariectomy in Rats.” Front Neurosci. 2018 Sep 3;12:557. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00557. Erratum in: Front Neurosci. 2018 Oct 12;12:738. PMID: 30233288; PMCID: PMC6129615. ↩︎

- Thompson C. “Discontinuation of antidepressant therapy: emerging complications and their relevance.” J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:541-8. ↩︎

- Agelink MW, Zitzelsberger A, Klisser E. “Withdrawal syndrome after discontinuation of venlafaxine.” Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1473-4. ↩︎

- Weir, Kirsten. “How hard is it to stop antidepressants? New research suggests antidepressant withdrawal symptoms might be more common, more severe and longer lasting than previously realized.” Monitor on Psychology. 2020. Vol. 51, No. 3. April 2020. American Psychological Association. Accessed February. 2024. ↩︎

- aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW et al. “Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression.” Biol Psychiatry. 2010; 67: 139-145 ↩︎

- Short B, Fong J, Galvez V, Shelker W, Loo CK. “Side-effects associated with ketamine use in depression: a systematic review.” Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Jan;5(1):65-78. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30272-9. Epub 2017 Jul 27. PMID: 28757132. ↩︎

- Short B, Fong J, Galvez V, Shelker W, Loo CK. “Side-effects associated with ketamine use in depression: a systematic review.” Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Jan;5(1):65-78. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30272-9. Epub 2017 Jul 27. PMID: 28757132. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674 ↩︎

- IsHak WW, Hamilton MA, Korouri S, et al. “Comparative Effectiveness of Psychotherapy vs Antidepressants for Depression in Heart Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(1):e2352094. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.52094 ↩︎

- Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, et al. “Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: An individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials.” JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(6):565-74. View abstract. ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.