By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

June 9, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

It is thought that in people with clinical depression, brain areas involved in the stress-response turn down the dial on mood-modulating neurotransmitters. St. John’s wort turns up the dial on a number of these neurotransmitters.

St. John’s wort can alter levels of many hormones like the stress-hormone cortisol and neurotransmitters including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) known for its calming effects; excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate, and norepinephrine; mood-modulating serotonin; and dopamine known for its role in reward, pleasure and motivation.

Neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky describes in a 2023 video how depression is a biological disease driven by stress. Dr. Sapolsky explains how neurochemicals like serotonin and the others listed above function in depression and how mood-boosting neurochemicals are turned down by stress.

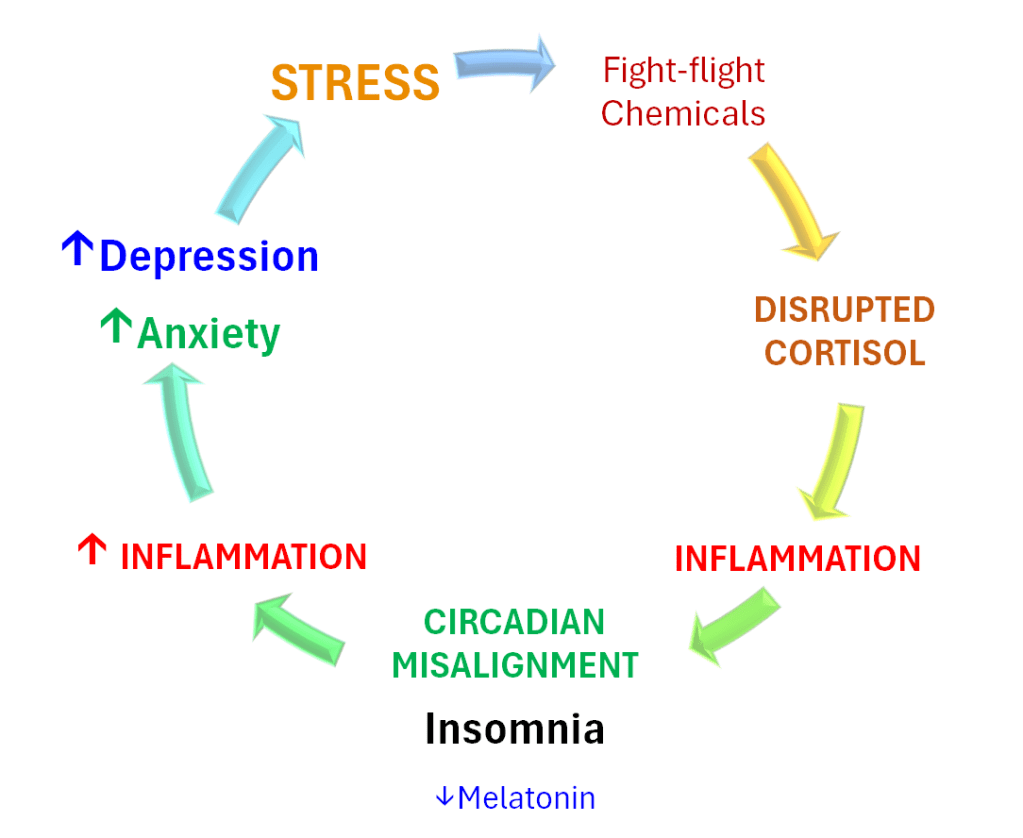

A key player in the body’s threat-response system is the stress-hormone cortisol. When there is a threat, including social threats like a spouse asking for a divorce, we become stressed. That activates the stress-response, releasing stress hormones including cortisol. This triggers inflammation in the body including the brain.

Stress and the inflammation it triggers can alter the circadian sleep clock and override the sleep drive, keeping us tossing and turning at night. Both stress-induced inflammation and insomnia can interfere with the brain’s ability to repair itself. The ability of the brain to repair itself by growing new connections is part of neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is essential for healing a depressed brain.

St. John’s wort has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. 1, 2 Animal studies of St. John’s wort have shown it can increase the brain’s adaptive capacity to respond to stress and augments neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, the brain’s regenerative capacity. 3

St. John’s wort also contains the sleep-hormone melatonin, known for its role in regulating circadian sleep clock. 4 And St. John’s wort can boost brain levels of one of the star-players in modulating mood— tryptophan, an amino acid found in food.

This botanical has a modest ability to regulate the dial on the body’s stress-response physiology.5, 6 It can modulate key stress-hormone, cortisol, sometimes increasing its levels, 7 sometimes reducing levels as has been found in the brains of rats. 8 But it may modulate stress more through its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. 9

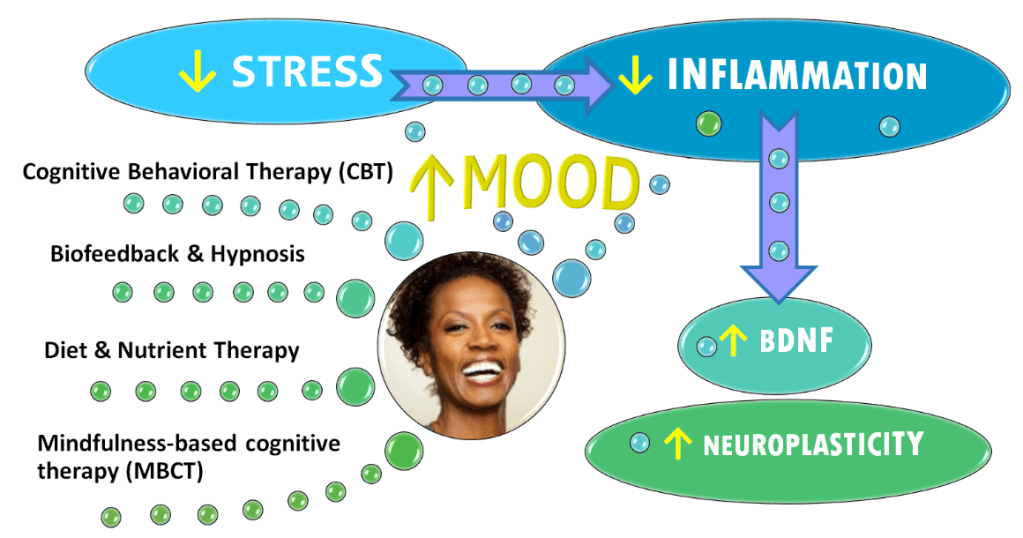

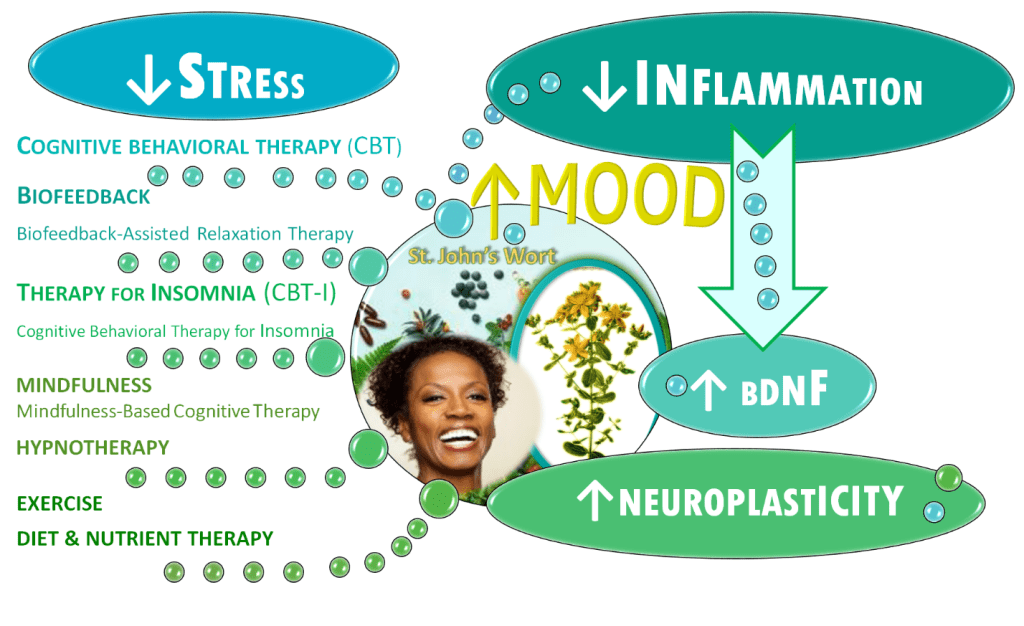

While St. John’s wort can help alleviate depression, its problematic drug interactions put the herb out of reach for many people. Click here to understand more about St. John’s Wort Safety problems. But the biochemical benefits of this botanical can be gotten in other ways that don’t involve the taking of tinctures or tablets and that are even more powerful for healing depression. These ways produce greater effects on depression than the St. John’s wort. Like the herb, they also modulate cortisol, calm stress, extinguish inflammation, boost neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, increase brain levels of tryptophan, normalize melatonin and ameliorating insomnia. If you want to learn how and why, read on.

A scientific consensus is beginning to emerge saying that treatments that trigger the growth of new nerve cells—a process called neurogenesis—are a way out of depression. The common factor could be brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a pivotal molecule regulating this process. “The vast majority of studies have confirmed the effect of antidepressants on BDNF levels,” according to a psychiatric literature review. 10

BDNF levels are reduced in people with major depressive disorder and increase after the depression remits. 11, 12 Scientists postulate that decreased production of BDNF contributes to depression by impairing regeneration of brain tissue. 13 Another depression promoter is inflammation.

Inflammatory lifestyle factors such as poor diet, inactivity, insufficient sleep, inadequate stress management or a string of high-impact stressors can lead to chronic elevation in stress chemicals like cortisol. Chronic activation of the fight-or-flight response—the body’s reaction to threats and stress—triggers the release of hormones and neurotransmitters. This unleashes a cascade of biochemical consequences leading to decreased neuroplasticity.

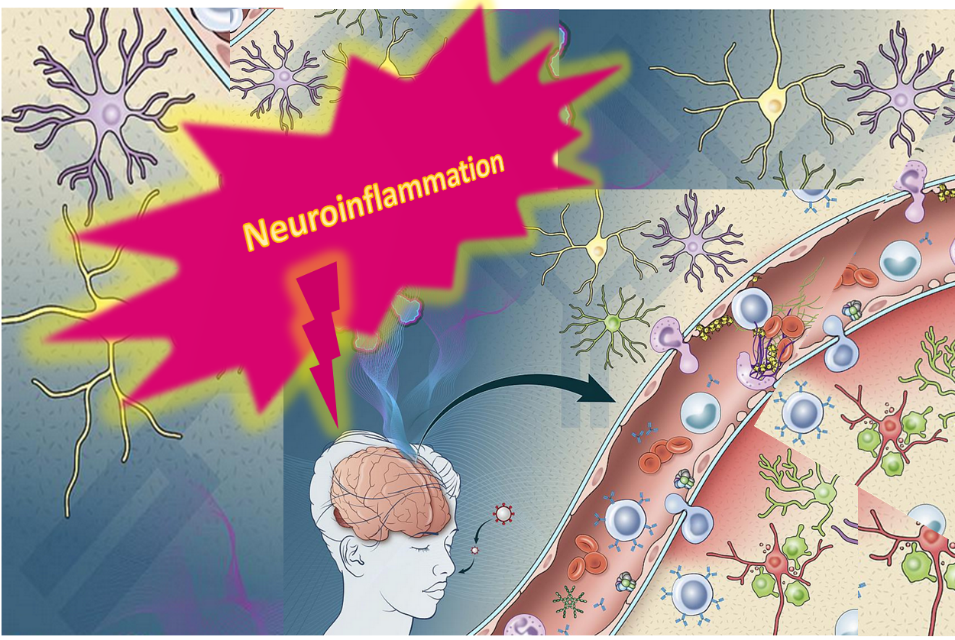

Inflammation has numerous ways to interfere with the brain’s regenerative capacity—its neuroplasticity. Inflammation leaks in between brain neurons throwing a monkey wrench into the brain’s neural circuitry. At the same time, stress significantly decreases BDNF, which could have helped restore the damage done to neuroplasticity. 14, 15, 16

Data spanning 5,166 depressed patients compared markers of inflammation in patients with depression with healthy controls. The researchers concluded that “Depression is confirmed as a pro-inflammatory state.” 17 Inflammation of the nervous system affects almost a third of patients with major depression. 18

Inflammation has been linked to changes in how our brains process emotional information. 19

High levels of inflammation may be the reason that antidepressants and other treatments don’t work that well as they could. 20, 21, 22 Neuroinflammation is linked with more severe, chronic depression that can be difficult to heal with conventional treatments. 23

Don’t despair, because the ability to reduce neuroinflammation and increase neuroplasticity are but a hop-skip-and-a-jump away, literally.

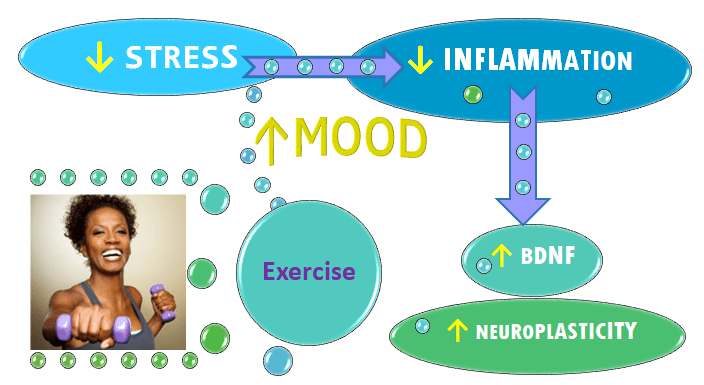

Exercise24 and stress management25 both slash inflammation. And exercise and mindfulness-based practices both markedly boost BDNF and neuroplasticity. 26 Anti-inflammatory diet can improve depression and cut inflammation. 27

Even a single session of exercise raises BDNF, which has been shown to bring a broad range of positive results for mood, learning and physical health, according to 2015 meta-analysis of 29 studies encompassing 1,111 subjects, some of whom had major depression. The researchers concluded that “exercise may help rescue the low resting BDNF levels often observed in depressed patients and exercise produces effects in a similar range to those of antidepressants.” 28 And exercise boosts endorphins.

Click link to learn how Exercise is Better than Drugs for Lifting Mood.

Not yet ready to move your body? You can start by focusing your mind.

Mindfulness-based interventions can significantly boost BDNF levels, according to a 2020 analysis of eleven randomized controlled trials including 479 patients with various conditions including depression. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy increased the levels of BDNF, the study found. 29

Learn more about mindfulness by clicking link below:

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: A Swiss-Army Knife for Tackling Anxiety & Depression

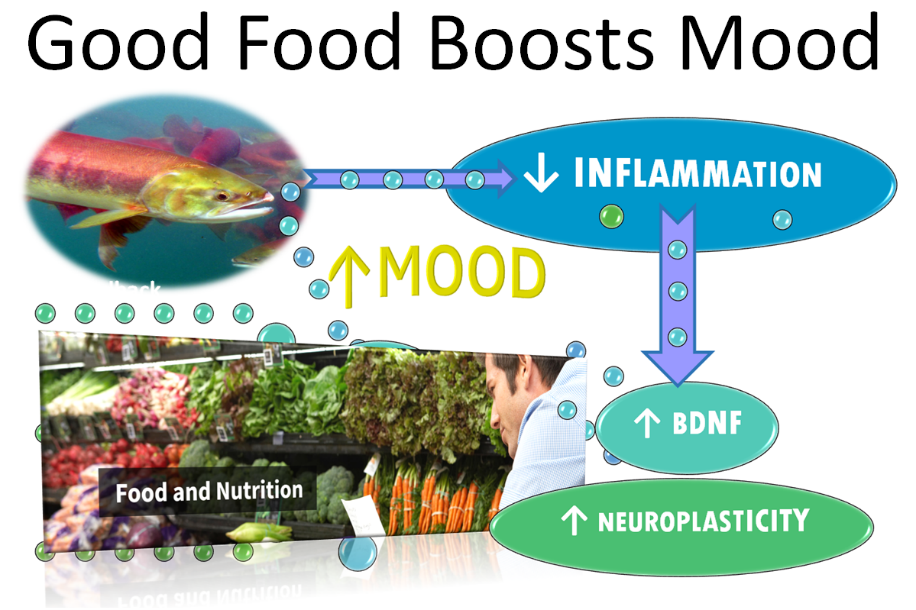

Making dietary and nutritional changes in combination with moving your body changes can slash inflammation and boost mood and BDNF. 30, 31

Those receiving expert nutrition counseling were encouraged to eat a modified version of the Mediterranean diet because it offered more flexible choices than a traditional, anti-inflammatory Mediterranean diet. A 2017 randomized controlled trial of 67 depressed patients sought to answer the question: “If I improve my diet, will my mental health improve?” At the end of 12 weeks, 32.3% of the patients who got nutrition counseling achieved remission from moderate to severe depression while just 8.0% of the social support control group did.32

Want to know which Foods that Stress and Depress and which Foods that Promote Well-being. Click previous link.

Extracts of St. John’s wort strongly reduce tryptophan degradation in test tube studies. 33 Tryptophan is an amino acid we get from food which plays an important role in mood and sleep. Its role in sleep is via its status as a precursor to melatonin. Tryptophan’s role in mood regulation is thought to relate to its effects on serotonin and how tryptophan break-down products affect the brain. To learn more about tryptophan’s mood-regulating affects and its role in depression, click here: Low Tryptophan = Low Serotonin. Does Low Serotonin = Depression?

Both the antidepressant drugs, SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) and the herbal medicine St. John’s wort boost serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in everything from mood, thinking, memory and blood pressure. People who meditate have higher levels of both serotonin and melatonin, the body’s main sleep hormone. 34

But researchers have shown that meditation also raises nighttime melatonin.35

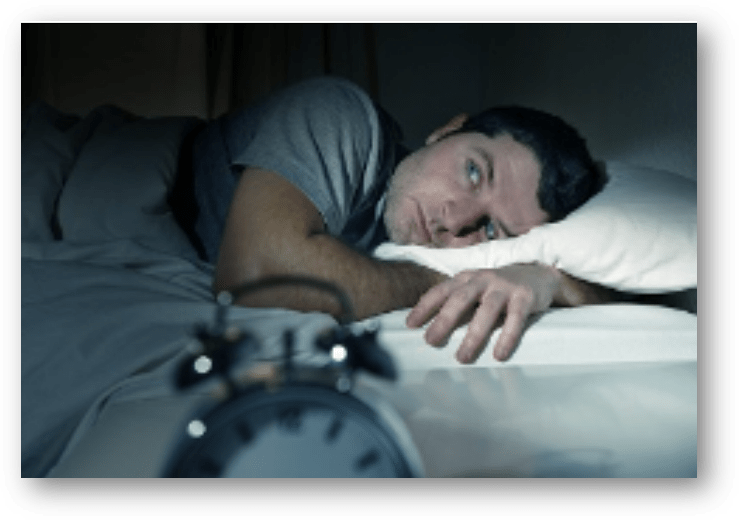

Sleep problems are a notorious depression trigger. Insomnia spikes inflammation and sleep problems exacerbate depression symptoms.

Insomnia may increase risk of developing depression tenfold, according to article in Hopkins Medicine. Other research suggests that up to 90% of people with major depression report sleep disturbances. 36

A disrupted sleep clock—too much, too little or fragmented sleep—can lead to depression because circadian rhythms have a profound impact on mood.

When depression hits, it lowers melatonin production, disrupts sleep and the circadian sleep clock.

A study found that depression severity was correlated with the amount of circadian misalignment: when your body’s internal clock is out of whack with the actual time of day. “The more delayed, the more severe the symptoms.” 37

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) has been shown to reduce the severity of insomnia and depression, according to a 2023 analysis of seven studies spanning 3,597 in adults diagnosed with both. The researchers concluded that it was “effective in alleviating insomnia and depression.” 38

Sleep problems help cement depression by perpetuating a vicious cycle fueled by stress. Learn more by clicking link: INSOMNIA’S UNBIDDEN BEDFELLOWS: Anxiety & Depression

Stress is king pin in the vicious cycle of depression. Stress is a trigger of inflammation and mental disorders such as anxiety and depression. 39 Stress can be battles with your boss, being buried by bills or a pending divorce.

Prolonged periods of stress often precede depression.

Chronic stress disrupts cortisol levels. Stress can cause a roller coaster of vacillating stress hormones.

Stress both elevates cortisol and, when it goes on too long, it can deplete cortisol levels. Elevated—and sometimes decreased—levels of the stress hormone cortisol are frequently found in depressed individuals. 40

Chronic stress triggers inflammation, which then lowers BDNF.

But we can balance cortisol and reduce stress without taking St. John’s wort with stress-busting techniques like biofeedback, which can calm cortisol 41 and dramatically lower stress. 42

After biofeedback training, levels of stress, anxiety, and depressive thinking fell and heart rate patterns consistent with relaxation rose, researchers found. People in the control group showed no such improvements. 43

Biofeedback improves depressive symptoms, a 2021 analysis of 14 randomized controlled studies including 794 participants concluded. 44

Want to know how to lower stress with biofeedback? Click link: How to De-Stress Your Way Out of Anxiety and Depression

Hypnotherapy also lowers stress.

A hypnotic intervention reduced test anxiety and also lowered blood levels of the stress hormone cortisol, researchers showed. 45 Women receiving hypnotherapy after giving birth had significantly lowered cortisol levels, a study found. 46

A 2021 randomized study comparing the gold-standard depression treatment—cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—to hypnotherapy in patients with mild to moderate depression, showed that hypnotherapy over 6 months is at least as effective as CBT for reducing symptoms of depression. 47

To learn more about hypnotherapy click link: Harness Hidden Strengths with Hypnotherapy

Counseling is as effective in treating unipolar depression as St. John’s wort or pharmaceuticals like SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) such as Prozac. People often take antidepressants while they are working with a counselor.

The evidence-based counseling techniques for unipolar depression that are endorsed by psychologists include:

- Behavior Activation (BA)

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

Optimal selection of the type of talk therapy is based on the individual’s unique characteristics and the severity of the depression symptoms. The most important factor in any form of psychological counseling is the quality of the rapport between the counselor and the patient.

Skills learned through counseling using techniques like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and biofeedback-assisted relaxation training produce more enduring benefits than antidepressant medications and St. John’s wort. Talk therapies teach us how to ramp down stress without medication.

Talk therapy can have just as strong an impact on the biology of depression as any medication or supplement without the risk of serious side effects, withdrawal symptoms or dangerous drug interactions.

Brain-imaging studies appear to be consistent with the idea that depression emerges when parts of the brain that dampen the body’s response to threats are dysregulated. This includes areas of the brain responsible for triggering the fight-or-flight response. The stress response releases cortisol and other stress chemicals that spike inflammation. In these studies, CBT has been shown to normalize this dysregulation, calming the overactivation in the threat-response regions of the brain in depressed patients. 48

To learn more about how the skills learned in talk therapy calm the stress response, click link: Talk Therapy Changes the Brain with Lasting Benefits

Talk therapies like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) may be more effective than medication for depression. The most common antidepressant drugs got bottom-of-the barrel results in a landmark systematic review comparing the drugs’ effect on depression with that of the talk-therapy CBT and a range of exercise modalities, according to data published by the prestigious British Medical Journal in February 2024. The results were comparable to what other meta-analyses have found for SSRI antidepressants. 49, 50

To learn more about how effective the counseling technique called CBT is for healing depression, click link: CBT First on List for Depression and Anxiety

To find out how Mood Change Medicine helps people with depression, click link below:

The information provided on this site is for educational purposes only; it is not medical advice and should not be substituted for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional before starting or stopping any medications or supplements.

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Bonaterra GA, Schwendler A, Hüther J, et al. “Neurotrophic, Cytoprotective, and Anti-inflammatory Effects of St. John’s Wort Extract on Differentiated Mouse Hippocampal HT-22 Neurons.” Front Pharmacol. (2017) 29403374 ↩︎

- Hunt, E. J., Lester, C. E., Lester, E. A., and Tackett, R. L. “Effect of St. John’s wort on free radical production.” Life Sci. 2001. 6-1-2001;69(2):181-190. View abstract. ↩︎

- Bonaterra GA, Schwendler A, Hüther J, et al. “Neurotrophic, Cytoprotective, and Anti-inflammatory Effects of St. John’s Wort Extract on Differentiated Mouse Hippocampal HT-22 Neurons.” Front Pharmacol. (2017) 29403374 ↩︎

- Chung MH, Deng TS. “Effects of circadian clock and light on melatonin concentration in Hypericum perforatum L. (St. John’s Wort).” Bot Stud. 2020 Sep 15;61(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40529-020-00301-6. PMID: 32930904; PMCID: PMC7492311. ↩︎

- Lawvere S, Mahoney M “St Johns wort.” Am Fam Phys 2005. 72:2249-5. ↩︎

- Butterweck V, Hegger M, Winterhoff H “Flavonoids of St. Johns Wort Reduce HPA Axis Function in the Rat.” Planta Medica. 2004. 70:1008-11. ↩︎

- Schule C, Baghai T, Ferrera A, Laakmann G. “Neuroendocrine effects of Hypericum extract WS 5570 in 12 healthy male volunteers.” Pharmacopsychiatry. 2001;34:S127-33. View abstract. ↩︎

- Franklin M, Reed A, Murck H. “Sub-chronic treatment with an extract of Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) significantly reduces cortisol and corticosterone in the rat brain.” Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004 Jan;14(1):7-10. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(03)00038-5. PMID: 14659982. ↩︎

- Zafir A, Banu N. Antioxidant potential of fluxetine in comparison to curcuma longa in restraint-stressed rats. Euro J Pharmacol. 2007;572:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.062. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Mosiołek A, Mosiołek J, Jakima S, Pięta A, Szulc A. “Effects of Antidepressant Treatment on Neurotrophic Factors (BDNF and IGF-1) in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).” J Clin Med. 2021 Jul 30;10(15):3377. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153377. PMID: 34362162; PMCID: PMC8346988. ↩︎

- Zelada MI, Garrido V, Liberona A, Jones N, Zúñiga K, Silva H, Nieto RR. “Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) as a Predictor of Treatment Response in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): A Systematic Review.” Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 30;24(19):14810. doi: 10.3390/ijms241914810. PMID: 37834258; PMCID: PMC10572866. ↩︎

- Meng F., Liu J., Dai J., Wu M., Wang W., Liu C., et al.. (2020). “Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in 5-HT neurons regulates susceptibility to depression-related behaviors induced by subchronic unpredictable stress.” J. Psychiatr. Res. 126, 55–66. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.05.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Zelada MI, Garrido V, Liberona A, Jones N, Zúñiga K, Silva H, Nieto RR. “Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) as a Predictor of Treatment Response in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): A Systematic Review.” Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 30;24(19):14810. doi: 10.3390/ijms241914810. PMID: 37834258; PMCID: PMC10572866 ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Emanuele F. Osimo, Toby Pillinger, Irene Mateos Rodriguez, Golam M. Khandaker, et al. “Inflammatory markers in depression: A meta-analysis of mean differences and variability in 5,166 patients and 5,083 controls.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. Vol. 87,2020, Pages 901-909, doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.02.010. sciencedirect ↩︎

- Raison CL, Miller AH. “Is depression an inflammatory disorder?” Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13:467–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Maydych V. The Interplay Between Stress, Inflammation, and Emotional Attention: Relevance for Depression. Front Neurosci. 2019 Apr 24;13:384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00384. PMID: 31068783; PMCID: PMC6491771. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Lopresti AL. “Cognitive behaviour therapy and inflammation: A systematic review of its relationship and the potential implications for the treatment of depression.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;51(6):565-582. doi:10.1177/0004867417701996 ↩︎

- Strawbridge R, Marwood L, King S, et al. “Inflammatory Proteins and Clinical Response to Psychological Therapy in Patients with Depression: An Exploratory Study.” J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 2;9(12):3918. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123918. PMID: 33276697; PMCID: PMC7761611. ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389 ↩︎

- Stoyan Dimitrov, Elaine Hulteng, and Suzi Hong. “Inflammation and exercise: Inhibition of monocytic intracellular TNF production by acute exercise via β2-adrenergic activation” by in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. Published online December 21 2016 doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.017 ↩︎

- Maydych V. The Interplay Between Stress, Inflammation, and Emotional Attention: Relevance for Depression. Front Neurosci. 2019 Apr 24;13:384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00384. PMID: 31068783; PMCID: PMC6491771. ↩︎

- Gomutbutra P, Yingchankul N, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn S, Srisurapanont M. “The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials.” Front Psychol. 2020 Sep 15;11:2209. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02209. PMID: 33041891; PMCID: PMC7522212. ↩︎

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. “A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’trial).” BMC Med. 2017. 15:1–13. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. “A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor.” J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Jan;60:56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. Epub 2014 Oct 12. PMID: 25455510; PMCID: PMC4314337. ↩︎

- Gomutbutra P, Yingchankul N, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn S, Srisurapanont M. “The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials.” Front Psychol. 2020 Sep 15;11:2209. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02209. PMID: 33041891; PMCID: PMC7522212. ↩︎

- Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. “Docosahexaenoic acid dietary supplementation enhances the effects of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition.” Neuroscience. 2008;155:751–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Wani AL, Bhat SA, Ara A. “Omega-3 fatty acids and the treatment of depression: a review of scientific evidence.” Integr Med Res. 2015 Sep;4(3):132-141. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2015.07.003. Epub 2015 Jul 15. PMID: 28664119; PMCID: PMC5481805. ↩︎

- Jacka FN, O’Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. “A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’trial).” BMC Med. 2017. 15:1–13. 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Winkler, C., Wirleitner, B., Schroecksnadel, K., Schennach, H., and Fuchs, D. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) counteracts cytokine-induced tryptophan catabolism in vitro. Biol.Chem 2004;385(12):1197-1202. View abstract. ↩︎

- JC Thambyrajah, HW Dilanthi, SM Handunnetti, DWN Dissanayake. “Serum melatonin and serotonin levels in long-term skilled meditators.” EXPLORE. Vol. 19, Issue 5,2023, Pages 695-701, ISSN 1550-8307, doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2023.03.006. sciencedirect ↩︎

- Gregory A. Tooley, Stuart M. Armstrong, Trevor R. Norman, Avni Sali. “Acute increases in night-time plasma melatonin levels following a period of meditation.” Biological Psychology. 2000. Vol. 53, Issue 1, Pages 69-78. ↩︎

- Franzen P.L., Buysse D.J. “Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications.” Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2008;10(4):473–481. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/plfranzen. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Emens J, Lewy A, Kinzie JM, Arntz D, Rough J. “Circadian misalignment in major depressive disorder.” Psychiatry Res. 2009;168(3):259–61. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.009 . [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Lin, Wenyao. Li, Na. Yang, Lili. Zhang, Yuqing. “The efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials” PeerJ. 2023; 11: e16137. Published online 2023 Oct 31. doi: 10.7717/peerj.16137

PMID: 37927792 PMCID: PMC10624170 ↩︎ - Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020. Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Boyce, Philip, Barriball, Erin. “Circadian rhythms and depression.” Australian Family Physician. Vol. 39, Issue 5, May 2010. AFP. ↩︎

- Makaracı Y, Makaracı M, Zorba E, Lautenbach F. “A Pilot Study of the Biofeedback Training to Reduce Salivary Cortisol Level and Improve Mental Health in Highly-Trained Female Athletes.” Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2023 Sep;48(3):357-367. doi: 10.1007/s10484-023-09589-z. Epub 2023 May 19. PMID: 37204539. ↩︎

- Schumann A, Helbing N, Rieger K, Suttkus S, Bär KJ. “Depressive rumination and heart rate variability: A pilot study on the effect of biofeedback on rumination and its physiological concomitants.” Front Psychiatry. 2022 Aug 25;13:961294. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.961294. PMID: 36090366; PMCID: PMC9452722. ↩︎

- Schumann A, Helbing N, Rieger K, Suttkus S, Bär KJ. “Depressive rumination and heart rate variability: A pilot study on the effect of biofeedback on rumination and its physiological concomitants.” Front Psychiatry. 2022 Aug 25;13:961294. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.961294. PMID: 36090366; PMCID: PMC9452722. ↩︎

- Pizzoli SFM, Marzorati C, Gatti D, Monzani D, Mazzocco K, Pravettoni G. “A meta-analysis on heart rate variability biofeedback and depressive symptoms.” Sci Rep. 2021 Mar 23;11(1):6650. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86149-7. PMID: 33758260; PMCID: PMC7988005. ↩︎

- Hamzah, F., Mat, K. C., & Amaran, S. (2021). “The effect of hypnotherapy on exam anxiety among nursing students.” Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, 19(1), 131–137. doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2020-0388 PubMed Google Scholar ↩︎

- S. H., Sulistyowati, S., Budihastuti, U. R., & Prasetya, H. “The Effect of Hypnotherapy on Serum Cortisol Levels in Post-Cesarean Patients.” Journal of Maternal and Child Health. (2021). 6(3), 258–266. Retrieved from thejmch.com/index.php/thejmch/article/view/587 ↩︎

- Fuhr K, Meisner C, Broch A, et al. “Efficacy of hypnotherapy compared to cognitive behavioral therapy for mild to moderate depression – Results of a randomized controlled rater-blind clinical trial.” J Affect Disord. 2021;286:166-173. View abstract. ↩︎

- DeRubeis RJ, Siegle GJ, Hollon SD. “Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms.” Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Oct;9(10):788-96. doi: 10.1038/nrn2345. Epub 2008 Sep 11. PMID: 18784657; PMCID: PMC2748674. ↩︎

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al.“Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.”Lancet. 2018; 391:1357-66. doi:10.1016S0140-6736(17)32802-7. pmid:29477251 PubMed Google Scholar ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.