By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

July 7, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

For more than two millennia, kava beverages have been used for many purposes, including medicinally to relieve muscle tension and for anxiety, stress, and insomnia. The consumption of beverages made with this intoxicating, Polynesian herb kava kava (piper methysticum) have been a social practice among Pacific Islanders for thousands of years. More recently, it has come to light that some people who take kava supplements might face significant health risks. And there’s no way to predict who could become one of the small number of people harmed by kava.

One can’t simply look at any particular treatment’s safety to know if its benefits outweigh risks. For example, if a treatment is effective at preventing death from a lethal illness, it might be worth taking it even if it’s very risky. But it wouldn’t make sense to take the risky treatment if are other safer treatments that are equally effective. That’s why when weighing kava’s benefits versus its risks, one needs to look at its potential risks and benefits for specific health conditions as well as the effectiveness and safety of other available treatments.

Kava’s Potential Risks

It might seem counterintuitive that kava could be dangerous given that it has been used apparently safely for more than 2000 years. And indeed, experts report that kava supplements and teas seem to be “well tolerated.” 1 But the risk of liver toxicity has come to light over the last three decades. Between 50 and 100 cases of liver injury have been reported during that time, according to the National Institutes of Health. 2

In the early 2000s, kava was banned or restricted in many countries such as Germany, Switzerland, France, Canada, and Great Britain. After reviewing the evidence, most countries have allowed kava to return to the market. 3, 4 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) never took kava off the market. But it has issued a consumer advisory alert for dietary supplements containing kava due to issues like liver failure.

An expert panel of physicians and pharmacists at NatMed Pro recommend that physicians screen patients who regularly use kava for liver abnormalities. 5 People with liver disease should use caution when taking kava, according to clinical practice guidelines from an international taskforce of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). 6

“Although liver toxicity is more frequently associated with prolonged use of very high doses, in some cases the use of kava for as little as 1-3 months has been associated with the need for liver transplants, and even death. In susceptible patients, symptoms can show up after as little as 3-4 weeks of kava use,” according to an expert panel of physicians and pharmacists. 7

Though these experts report that liver transplants and death is rare in people taking kava for less than one month, 8 liver test abnormalities and memory deficits have been found in a 16-week study of participants taking kava. 9

“Kava extracts have been used safely in clinical trials under medical supervision for up to 6 months,” according to a peer-review report from NatMed Pro.10

This sort of medical supervision typically involves screening for liver abnormalities by using blood tests. When such tests show elevated levels of liver enzymes it means that cells in the liver are being destroyed in abnormally high numbers. The higher the levels of liver enzymes found in tests, the higher the numbers of liver cells dying. Over time, if enough liver cells are damaged, a person can develop cirrhosis of the liver, which can eventually cause the liver to fail.

Liver function tests can be elevated after 3-8 weeks of kava use, according to article in the British Medical Journal. But elevated liver enzymes have rarely led to liver enlargement and brain pathology. 11 Liver symptoms reported in the kava literature include yellowing eyes or skin, unusual tiredness, and dark urine. 12, 13 Symptoms of liver injury may include persistent nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, abdominal pain and light-colored stools.

But numerous studies have not found liver abnormalities or other problems in people taking kava.

There were no significant differences in liver function tests in those who took kava compared to those who took an inert placebo that contained no kava in a 2013 double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled study investigating adverse reactions, liver function, as well as the addictive potential of kava supplements in 75 people with generalized anxiety. 14 This 6-week kava study found no significant adverse reactions, withdrawal symptoms or signs of addiction that could be attributed to kava. Other small studies of shorter duration also showed no adverse events or elevated liver function tests in those taking kava supplements for generalized anxiety disorder. 15

But it’s also true that participants in some kava studies have been found to have evidence of liver test abnormalities and other concerning symptoms.

Patients on a 16-week course of kava had more frequent liver function test abnormalities compared to those not taking kava, although no participant met criteria for liver injury. This larger, 171-participant, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study—also showed those who took kava supplements had poorer memory and increased tremors or shakiness compared to the placebo group. 16

While these results could mean that longer term use of kava elevates the risk of liver injury, we can’t rule out other factors like genetic make-up of study participants being in play in kava-related liver toxicity. If a genetic difference is the cause of liver injury, we don’t have any tests to warn those who might be injured by kava.

Researchers analyzed 36 case reports of hepatitis (liver problems) in people who took kava. They found serious liver damage was correlated with the cumulative kava dose. The time it took these people to develop liver problems after taking kava was highly variable. The researchers reported that “nine patients developed fulminant liver failure, of which eight patients underwent liver transplantation.” Three patients died, two following unsuccessful liver transplantation. In all other patients, a complete recovery was seen after withdrawal of kava. They hypothesized that genetic factors as a potential cause. 17

Case reports point to the possibility that many factors increase the risk of permanent liver damage including long-term use, 18 high dosage, 19 and combining kava with other substances that also carry the risk of liver toxicity risk such as alcohol 20, 21 and drugs like acetaminophen (Tylenol). 22, 23 People with current or previous liver problems may also be at increased the risk of liver damage when they take kava. 24

Any single factor or a combination of factors may account for liver injury associated with kava use. But a definitive cause for kava-related liver problems remains unresolved after decades of study, according to a World Health Organization kava safety report. 25

While there’s a very long history of kava beverage consumption among Pacific Islanders, its use in supplements is a recent development. Even in Pacific Island and Australian indigenous communities “where kava beverage is used, there is a clear association between increased levels” of a liver enzyme and moderate-to heavy kava beverage consumption, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) report. 26

Because kava beverages have been used for more than two millennia, it suggest that these beverages might be safe to consume. But the WHO concluded that before kava can be used with an acceptably low health risk, studies are necessary to assess possible factors in liver toxicity. Such studies should include selection of safe kava varieties, methods of kava beverage preparation, compositional parameters of kava beverages, and safe levels of kava consumption, WHO said. 27

Other possible causes of kava-related liver toxicity include: prolonged usage, overdosing, 28 contaminants in the kava raw material, mold 29, extraction methods 30, toxic constituents, 31 toxic breakdown products, 32, improper storage and handling, genetic vulnerability of consumers, 33 as well as drug–herb, 34 herb-herb, and/or herb-alcohol interactions, 35 various researchers have said.

One thing is clear, we can’t know with enough certainty, which of these factors could cause liver injury in any given individual.

We know that kava has been linked to liver injury that is sometimes serious and rarely fatal. But the frequency and cause(s) of all the cases of liver damage are unknown. There are so many possible causes of liver toxicity, that it’s not currently possible to provide workable guidelines for how to use kava with acceptably low levels of risk.

The risks of taking kava don’t begin and end with the potential risk of liver injury. Kava has other potential risks and side-effects.

Adverse Events & Side Effects

Kava might worsen Parkinson’s disease. 36, 37 It can cause headaches, memory impairments 38 and might cause retention of urine in the bladder. 39

Taking a kava supplement providing 120 mg of kavalactones twice daily for 16 weeks increases the risk for memory impairment by 55% when compared with placebo. 40

Kava beverage consumption caused temporarily impair visual abilities, according to a case report. 41

Kava is intoxicating and carries a risk of dependency. Drinking large amounts of kava tea led to a five-fold increase in serious motor vehicle crash resulting in death or serious injury, according to 2016 study. 42 Driving risks likely exist at normal doses and increases with increasing doses.

According to an expert panel of pharmacists and physicians, 43 rare serious adverse effects of kava include:

- Poor health in those who take very large doses of kava long-term including

- low body weight

- reduced protein levels

- puffy face

- blood in urine

- abnormalities in white and red blood cells

- lower numbers of blood components involved clotting which might impair clotting

- elevated heart rate and

- abnormal heart rhythms and problems breathing possibly due to pathological changes in blood pressure in the lungs

- High doses are linked to

- reddened eyes

- dry, scaly, flaky skin

- yellow discoloration of the skin, hair and nails

- Typical doses may cause

- involuntary facial movements

- twisting movements of the head and trunk

- tremors and

- parkinsonian-like symptoms

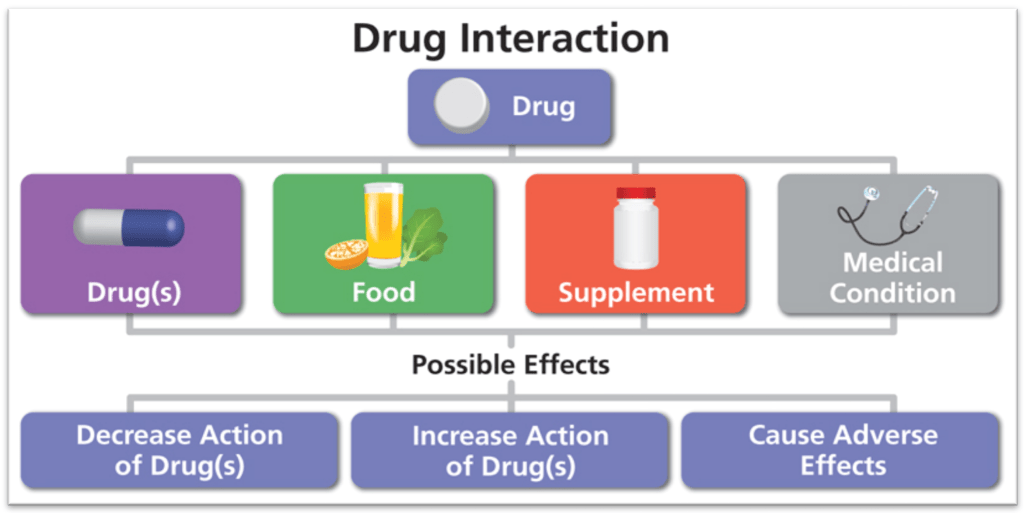

Kava’s additional risk also includes overdose and drug interactions. Compounds found in kava have caused death when administered intravenously in large doses. 44 Kava can interact with drugs and supplements, especially sedating medications and medications and substances that can raise liver enzymes like Tylenol and alcohol.

The active constituents (pyrones) in kava could endanger fetal development and cause a loss of uterine tone. Loss of uterine tone could increase the risk of post-partum bleeding. Pyrones also might be passed into breast milk posing a safety risk for infants. Kava may pose a safety risk for children.

Given its uncertain safety profile, it’s really important to weigh the potential risk of taking kava—risk that might even include death—against kava’s potential benefits for insomnia, depression and anxiety.

Do Kava’s Potential Benefits for Insomnia Outweigh Risks?

Kava is not well-studied for its impact on sleep. The few studies that exist show contradictory results.

It’s very clear that the possible benefits of taking kava for insomnia do not outweigh the risks. The herb’s dicey safety profile, combined with the fact that there are other, more effective insomnia treatments with excellent safety profiles such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) suggests sidelining kava.

While rat studies suggest that kava has sedating effects, 45, 46 there have been few studies in humans and the ones that do exist have conflicting results.

Most of those human kava sleep studies were conducted on people with anxiety disorders. One such study showed it effective for sleep in people with diagnoses of generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, common phobia or adaptation disorders. “Safety and tolerability were good, with no drug-related adverse events or changes in clinical or laboratory parameters,” a four-week, 2004, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study found. 47

Because this study was done with people who have anxiety, it provides little evidence that kava can improve sleep in people who don’t have an anxiety disorder.

But taking kava three times daily for 4 weeks did not improve sleep or anxiety any better than a sugar pill that doesn’t contain kava, according to a large, 2005 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 391 patients with self-reported insomnia associated with anxiety. 48

The results of this study point to anxiety improvements as the cause of any possible sleep improvements, providing more clues that kava might not help insomnia in people without anxiety. And because the results of kava studies conflict, it leads to the conclusion that kava’s efficacy for insomnia remains an open question for further research.

Kava has problematic safety profile. In some rare cases “the use of kava for as little as 1-3 months has been associated with the need for liver transplants, and even death. In susceptible patients, symptoms can show up after as little as 3-4 weeks of kava use,” according to an expert panel of physicians and pharmacists. 49 But the 391 patients in the 2005 study took kava for 4 weeks and it didn’t work any better than a sugar pill to improve their insomnia. 50 It might be that kava takes 5 weeks to manifest any possible efficacy (see section below entitled “Do Kava’s Potential Benefits for Anxiety Outweigh Risks?” )

If any of these 391 study participants had been susceptible, they might have experienced liver injury within the duration of the study. Thus, they would’ve experienced serious side effect without receiving any benefit. Granted that the cases of liver injury linked to kava are rare, but because we don’t know why these people had liver injury, we cannot predict who could have a serious side effect in the future. We don’t know who might have no improvement in their insomnia from taking kava, but have some sort of serious side-effect from it.

There are other safer botanicals that might provide equally effective symptomatic improvement for insomnia. For example, something as benign as tart cherry juice has been shown to modestly increases total sleep time and decrease the time spent in bed not sleeping, a 2011 study found. 51 Tart cherry juice also modestly improved insomnia severity, a 2010 study showed. 52

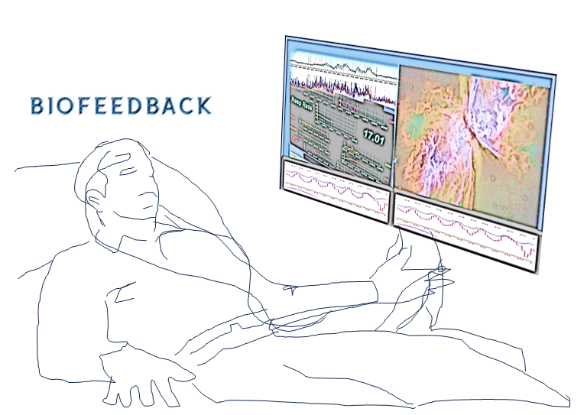

Any possible benefits of kava for sleep are likely due to its affects of decreasing anxiety. But these benefits also come with health risks. That makes other, safer anxiety treatments more attractive. Indeed, other therapies can reduce anxiety in minutes not weeks—the time frame that studies suggest is needed for kava to work. For example, biofeedback or hypnosis—treatments with no health risks—can rapidly decrease anxiety and some studies show biofeedback improves sleep quality, according to a 2022 study. 53

But more to the point, the fact that there are completely safe insomnia treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) that are cable of providing a permanent insomnia cure without the need to take pills, tinctures or juices leads, inevitably, to the conclusion that kava’s risks do not outweigh potential benefits.

No supplement can cure insomnia. CBT-I is a behavior-based treatment for many people without health risks.

For more information about a safe insomnia treatment shown to cure insomnia in the majority of study participants in numerous high-quality studies, click link below: DEFEATING INSOMNIA

Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for medical advice.

Do Kava’s Potential Benefits for Anxiety Outweigh Risks?

Though there are a lot of conflicting studies, the weight of the research shows that kava does not improve anxiety disorders, but may temporarily relieve feelings of anxiety. This could be because over time, kava and other anxiolytics may actually make anxiety worse.

Research results also conflict on the magnitude of kava’s anxiolytic effects. This may be related to kava’s different dosing; different length of time over which kava was used and the different levels of anxiety experienced by study participants prior to taking kava.

There’s a lot of kava studies with contradictory results. Some studies support the efficacy of kava for anxiety. 54, 55, 56 Other studies, especially studies in people with general anxiety disorder, show kava doesn’t work. 57, 58, 59, 60, 61

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine, a division of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), concluded that “kava supplements may have a small effect on reducing anxiety.” 62

But a 6-week study found that kava may have more than just a small effect. Researchers found kava to be moderately effective for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, according to a double-blind, randomized-controlled study comparing kava to a placebo in 75 people. 63 People with higher levels of anxiety had greater reductions in anxiety in the kava-treated group, the researchers found. The kava-treated group had more headaches. There were no other significant differences between the kava group in terms of any other adverse effects, and no differences in liver test results compared to the control group.

Two analyses of multiple clinical studies of people with mild-to-moderate anxiety found that kava extracts are significantly more effective than placebo (fake pill which contained no kava) and equally effective as the anti-anxiety benzodiazepine drugs like Valium, Ativan and Xanax. 64, 65

But other studies show kava doesn’t work for anxiety.

A large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 391 patients with self-reported insomnia associated with anxiety—found that taking kava three times daily for 4 weeks does not improve sleep or anxiety any better than a sugar pill which contained no kava. 66

When it comes to anxiety disorders, it looks like kava is ineffective.

People who took kava root tablets twice per day were less likely to be in remission from their anxiety disorder than those on the placebo (fake pill), according to a 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 171 currently non-medicated people diagnosed generalized anxiety disorder. And anxiety patients taking kava had poorer memory and more tremor and shakiness than the control group not on kava, the 2020 study found. Though kava was generally well tolerated, liver function test abnormalities were significantly more frequent in the kava group, although no participant met criteria for herb-induced hepatic injury. 67

Findings like liver function test abnormalities, memory issues and tremor, combined with growing evidence that kava provides no long-term benefit for anxiety strongly shift the balance towards the risk end of the scale. Especially for people with an anxiety disorders the benefits are lacking and the risks are too high, the research shows.

A 2011 comprehensive review of kava’s efficacy and safety by psychiatrists in Australia and New Zealand endorsed kava’s use for generalized anxiety disorder. 68 But a later 2023 report by a largely US-based expert panel of physicians and pharmacists states that “kava doesn’t seem to be effective for treating GAD [General Anxiety Disorder].” 69

It’s not just US-based experts that are down on kava for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). Clinical practice guidelines from an international taskforce of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) say that high-quality study 70, 71 results “have not shown supportive evidence for efficacy in treating GAD.” 72 The taskforce’s clinical practice guidelines recommend against the use of kava to treat patients with the anxiety disorder (GAD).

Many people have anxiety symptoms that don’t meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder. Anxiety can be disruptive, decreasing our quality of life. This type of anxiety is called subthreshold or subclinical anxiety. An anxiety disorder such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) involves excessive anxiety and worries that are hard to control. Worries surround a number of activities or events (e.g., work and school performance), occurring more days than not for months. People with general anxiety disorder can feel restlessness, a keyed-up or on-edge feeling. They may tire quickly or have difficulty concentrating. Irritability and muscle tension are very common. Sleep tends to be disturbed sleep because neurochemicals involved in the stress response override the body’s natural sleep drive. But the main difference between anxiety (subclinical) and an anxiety disorder is that the latter causes significant distress or significantly impairs social or occupational functioning.

The information contained on this website is not a substitute for medical diagnosis or advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional for medical advice and diagnose.

Since kava doesn’t appear to be effective for anxiety disorders, one can ask if people with less disruptive anxiety (subclinical anxiety) should consider taking it?

Citing a book about kava in the treatment of anxiety, 73 the international task force’s clinical practice guidelines cited above say that “short-term” use of certain strains of kava for general anxiety symptoms is “supported by robust evidence.” 74 But the guidelines say kava should be used with caution in people with liver issues, and it should not be taken by people on benzodiazepines like Xanax and Ativan, or those who use alcohol. The guidelines state that there is “fair safety data, although further data would be beneficial in determining causations of very rare liver issues (noted 15–20 years ago, potentially due to poor-quality kava).” 75

But even with these precautions, we have to ask if taking kava for subclinical anxiety makes sense based on the data.

Kava was not effective in people with subclinical anxiety that did not meet diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder, a 2022 analysis of three studies found. 76 Studies show that “kava’s effects appear to be dose-dependent and duration-dependent,” according to research. 77

Results of numerous studies, 78, 79, 80, 81 led experts to report that the data “suggests that kava extract must be taken for at least 5 weeks to provide a benefit.“ 82

Some efficacy data says kava might work in subclinical anxiety—for people without an anxiety disorder—if it’s taken at a high enough dose for a long enough period of time. But the safety data says the higher to dose and the longer the supplement is taken the riskier it is.

In two studies, 83, 84 one that found kava doesn’t work and the other found it does. Both studies postulated that genetic differences observed in study participants were a possible cause of kava’s lack of efficacy. So it’s possible for a person to risk taking kava for 5 weeks only to find that it won’t work due to their genetics.

The international taskforce (cited above) reinforces that we still do not know what causes kava-related liver injury. Their clinical guidelines say it might be due to poor-quality kava. But the World Health Organization listed many possible reasons besides the quality of the kava as possible causes for the cases of liver injury.

The international taskforce clinical guidelines assert kava as having “fair safety data” and says that “further data would be beneficial in determining causations of very rare liver issues” that were noted 15–20 years ago. 85 However, there is still a current risk of liver injury cited in the scientific literature as recently as 2020. A 2020 study found higher frequency of liver function test abnormalities and memory problems in people taking kava compared with those in the study not on kava. 86

The guidelines predicated safety upon “short-term” kava use. 87 But one can ask if “short-term” means less than 5 weeks? Because the data suggests that it takes that long to work.

The use of kava for as little as one month has been associated with the need for liver transplants and even death. “In susceptible patients, symptoms can show up after as little as 3-4 weeks of kava use,” according to an expert panel of physicians and pharmacists. 88 This means that the efficacy data is at loggerheads to the safety data even for short-term use in people with subclinical anxiety.

But there’s something else to consider which could be the reason why kava might work in subclinical anxiety and not in anxiety disorders. It’s all about the process of how anxiety is kindled into an anxiety disorder.

How Anxiety Disorder is Kindled: Can Kava Play a Role?

The difference between subclinical anxiety and an anxiety disorder is one of degree. Anxiety disorders are more severe than subclinical anxiety. Overtime subclinical anxiety can become a full-blown clinical disorder.

The process that promotes and maintains anxiety involves our repeatedly reinforcing the links between feared situations and our brain’s unconscious appraisals that those situations pose an actual safety threat.

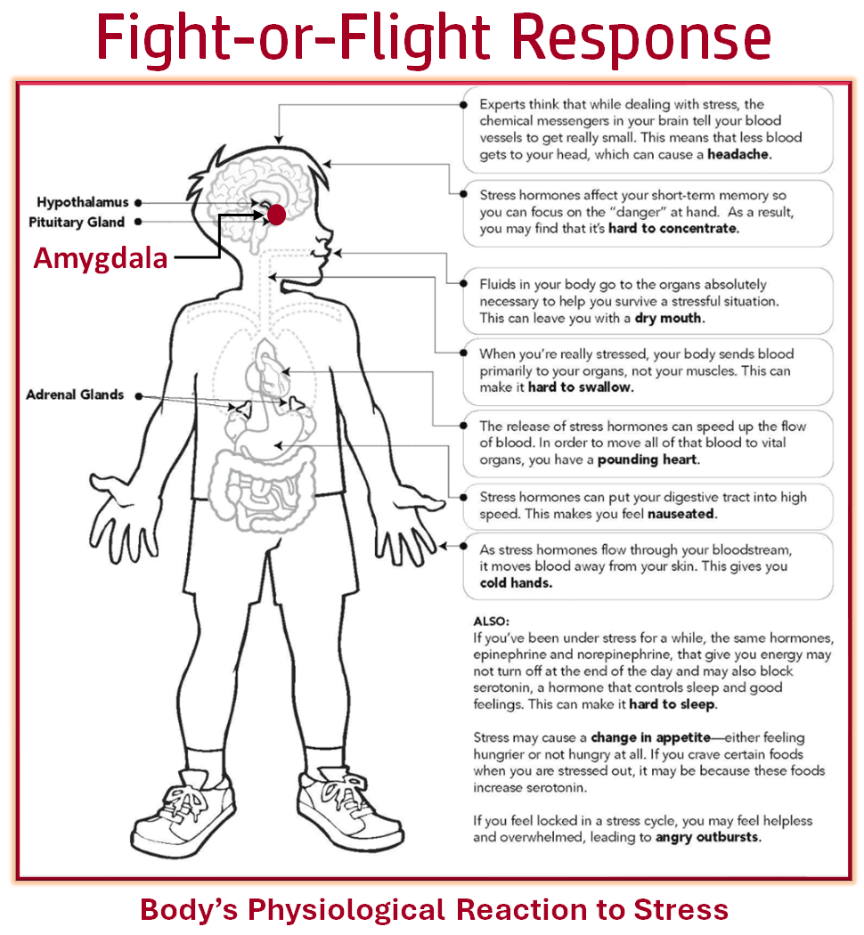

Our brains and bodies are designed protect us from danger. If we have to stop and think whether that saber-toothed tiger is an actual threat, we’d be dead before we could make that determination. Our unconscious processing is lightning fast and our senses as well as our behaviors tell us immediately if something is a threat to our survival or well-being.

When our brains register a threat, our biology instantly generates fearful emotions. The emotion of fear is what tells us something is dangerous before our conscious mind can process all the sensory information and reason to a “rational conclusion” that our fear makes sense based on the actual situation, not just our automatic fear response.

The fear response is shut down when our rational thinking lets us know that we are not in danger or that the danger is manageable with our current resources. It is also shut down by successfully navigating the fear-provoking situations themselves.

OPTIONAL READING: However, conscious thinking occurring after these situations can lead to more fear if our conscious minds ruminate on the fear-generating thoughts. Even years after the fear-provoking situation occurred, the fear can grow. For example, fear can increase before the anxiety-provoking event due to negative predictions made by people with social anxiety. Their anxiety will decrease right after the event when their experience of the event disconfirms their negative predictions. But it’s possible that years later, anxiety levels can rise higher than before or right after the event. This happens when people recycle anxious thoughts generated after the event.

Among the many things unconsciously processed by the brain which can trigger an automatic, instantaneous fear response (fight-flight response) is sensory information that resembles scary, early-life experiences and past adverse events. Signals triggered by our fear response including those related to blood pressure, heart and breathing rates and the level of tension in our muscles can feed back into the brain, further perpetuating anxious feeling.

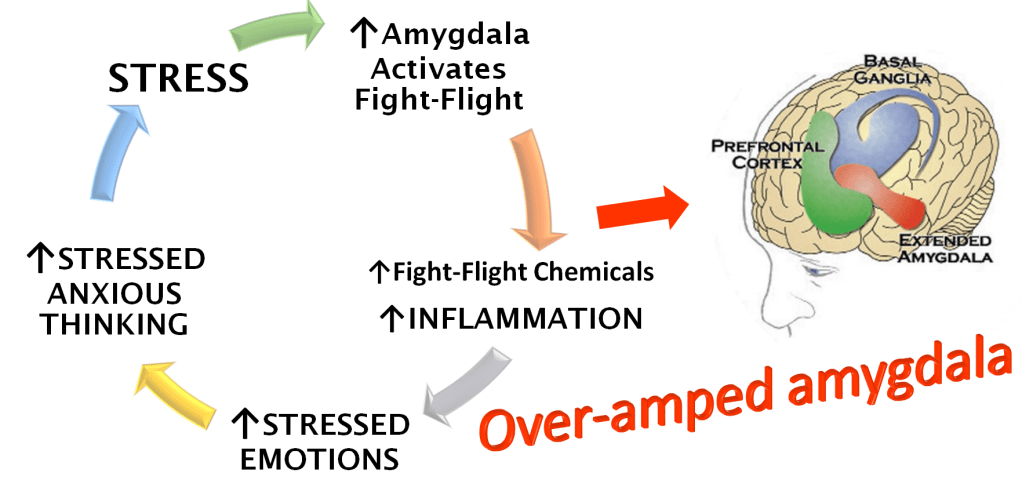

Anxious thoughts and the actions we take when we feel afraid, or even just before we face fear-provoking situations, also trigger fear. That’s because our brain’s unconscious processing takes into account our behaviors when it pulls the alarm on the fear response. When we do things based on the prediction that something is dangerous, that sends danger signals to parts of the brain responsible for triggering the fear response, also known as fight-or-flight response. This leads to more fear when the situation is encountered in the future. The more this happens, the more entrenched the anxiety becomes. A part of the brain that activates the fight-flight response called the amygdala grows in size, as our hypervigilance and reactivity to fear triggers grow.

Taking an anti-anxiety medication like Xanax or supplement like kava could maintain the vicious cycle that prevents recovery from an anxiety disorder by feeding more danger information to brain areas that generate the fear response. It also maintains anxiety by preventing the safety signals from feeding back to the brain.

When we successfully navigate what our bodies are telling us are dangerous threats, it creates safety signals. Safety signals come when meeting these challenges is not predicated on some external support. The stress-response is shut down and our bodies send biological signals that shut down the fight-or-flight responses. The resultant changes in blood pressure, heart rate, breathing and muscle tension send more safety signals back to the brain, furthing dampening the fear response.

By taking a pharmaceutical or natural supplement to prevent the unpleasant danger signals we get from our bodies—our emotions—we are relying on something that is external to overcome the percieved threat. That prevents successful navigation of the situations that trigger fear. When we encounter those situations again, there will be no safety signals generated because we’ve stolen the opportunity for the body to naturally shift from a state of high alert into a state of more calm as a result of successful navigation of what appeared to be an threat. In other words, things that prevent emotions like fear also prevent emotions like calm and sense of safety.

Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for medical advice.

Taking Tinctures & Tablets Could Make Anxiety Worse

Part of what provides long-term relief from most types of anxiety disorders is directly facing anxious feelings and the situations that cause them. Continually taking a substance that gives temporary relief keeps the anxiety going and can cause anxious feelings to persist and worsen in intensity over time. This is because each time we successfully navigate situations that trigger the stress response, our brains register the information that the threat is not insurmountable so that the next time we face these same situations the body’s stress response is dampened. We habituate to these triggers and overtime the anxiety gets less and less because we unconsciously come to unlink these triggering situations with a threat.

The quicker and deeper the anxiety relief from taking a substance, the greater the potential detriment to recovery from an anxiety disorder. This is because taking an anti-anxiety medication or supplement to prevent activation of the stress response strengthens the association between the anxiety-provoking situations and sense that these situations present a true danger. This makes the fear response worse the next time we encounter the same situations.

This holds true for kava possibly as much as for benzodiazepine—anti-anxiety medications like Xanax (alprazolam) and Klonopin (clonazepam).

Safety & Efficacy of Alternatives to Kava for Anxiety

We’ve seen that to achieve even uncertain efficacy for subclinical anxiety with kava requires taking it in potentially dangerous doses and durations. We’ve also seen that it doesn’t work for full-blown anxiety disorder like GAD. We’ve examined kava’s potential to make anxiety to worse. This brings us to the final part in our analysis of kava for anxiety: a look at the efficacy and safety of other anxiety treatments. If there are other treatments that are more effective and safer, we can conclude that kava’s risks outweigh its benefits.

One alternative to kava is to replace it with another botanical or pharmaceutical anti-anxiety medication.

The only botanical that has been conclusively proven effective for anxiety is kava, according to a 2006 systematic review of controlled clinical trials. 89 Although the research supporting ashwagandha efficacy has been mounting—depending on dose and duration—kava is one of the most potent of the botanicals for anxiety. But kava’s effectiveness takes a hit due to safety questions. It could be that the only way to get anxiety reductions from kava is to take doses that pose safety risks. Ashwagandha also comes with risks. Citing harmful effect on thyroid and sex hormones and potential to induce abortions, Denmark banned ashwagandha in April 2023.

There are other anti-anxiety supplements that offer a more favorable safety profile.

Mood Change Medicine’s website has reviewed a number of botanicals that people take for anxiety. Many these are discussed in this website’s article: “Plant Valium: Is Valerian Effective for Anxiety?” In this article, the efficacy of valerian as well as that of other botanicals is discussed. The safety of valerian is compared to that of the powerful benzodiazepines—anti-anxiety medications like Xanax (alprazolam) and Klonopin (clonazepam). The discussion includes details about the many dangers of these pharmaceuticals, one of which is death if the drugs are abruptly discontinued.

After considering the safety risks of both supplements and pharmaceuticals, many people may want to consider alternative treatments that don’t involve taking tablets or tinctures and are more effective.

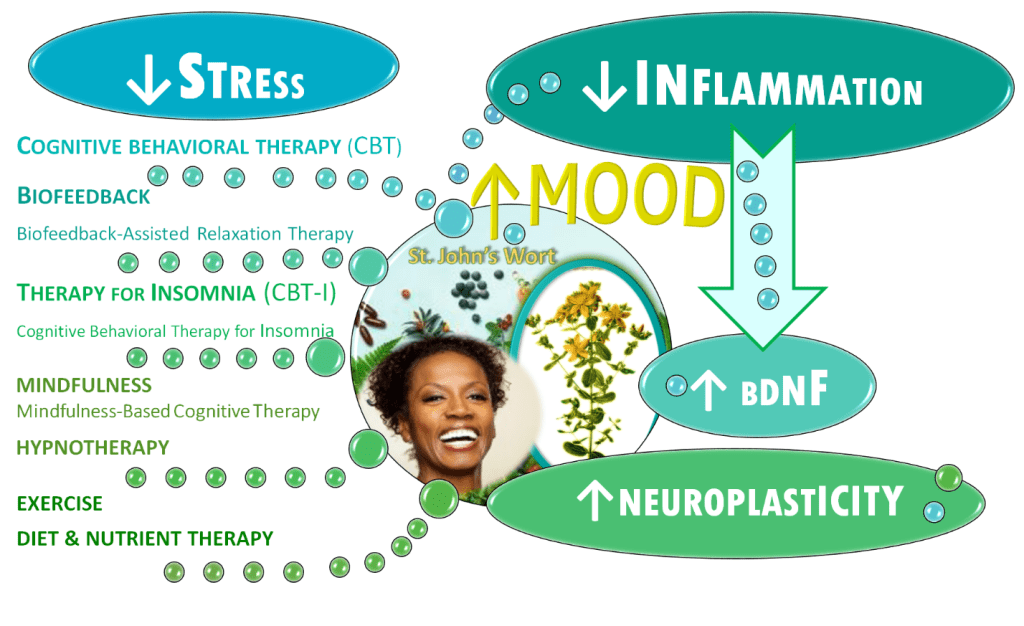

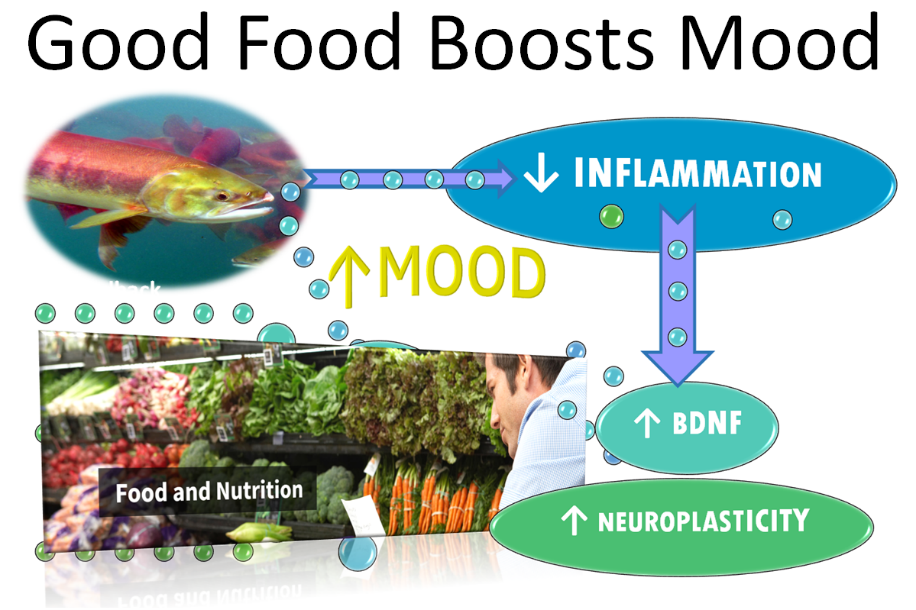

The safest and most effective alternative anxiety treatments are behavioral treatments such as talk therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based therapies like mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and hypnotherapy; biofeedback-based therapies like biofeedback-assisted relation training (BART) and heart rate variability training (HRV); exercise and movement-based therapies; and treatments that optimize sleep like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). Diet and nutrient therapy is another safe, evidence-based anxiety treatment.

Integrative Anxiety Treatment Rating Scales

Below are two rating scales designed to give readers a sense of how various anxiety treatments might play out in terms of their immediate and long-term effects on anxiety. They include ratings of evidence for the effectiveness of various anxiety therapies including behavioral treatments, lifestyle modifications, medications, botanicals and nutritional supplements as well as a comparison of their relative safety and health benefits.

It’s a difficult scale to construct because every person has unique biochemistry, temperament and history of experiences which shape how each anxiety treatment will work for that person. Therefore, readers are advised to take these scales with a large grain of salt. This is just one doctor’s considered opinion. Your experience could be very different than what the rating scales listed below suggest.

Because some treatments contain more than one therapeutic component, some items are listed twice to reflect various ways a type of treatment works.

Comments are included below each treatment to give the reader a sense of why a particular treatment got its rating. These comments also provide opinions about each treatment’s relative potency and how its potency might change with continued use over time. For example, a person experienced with mindfulness might be able to quickly and strongly shift out anxious states. But that would not be the case with someone who was doing mindfulness for the first time. Yet other comments provide information about the duration of time various treatments have been used safely in studies.

These scales do not include all possible botanicals, medications or behavioral treatments that are used for anxiety.

Strongest to weakest evidence of an anxiety treatment’s effectiveness taking into account the number of high-quality studies, the potential to cause long-term worsening of anxiety, whether benefits continue when treatment is discontinued and the length of time the treatment can be used effectively:

- Rated #1 Talk therapy (cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT)

- CBT is one of the first-line talk therapies used to treat anxiety. There is abundant research showing CBT is effective for anxiety.

- Benefits can be life long

- Does not cause long-term worsening of anxiety like drugs or supplements

- Anxiety levels can dramatically and rapidly decrease when an individual’s perspective of the anxiety trigger(s) shifts to one that is less fear-provoking.

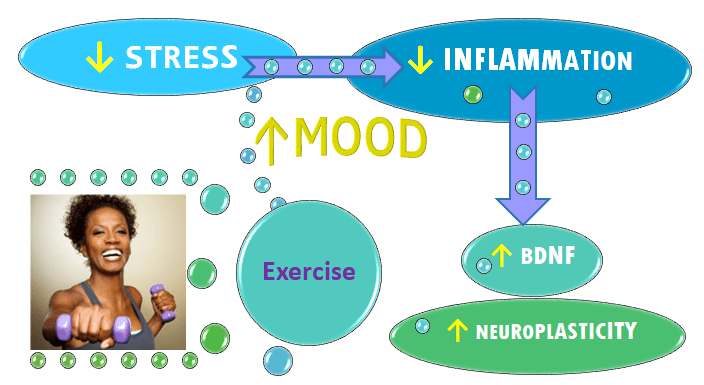

- Rated #2 Aerobic exercise such as swimming, aerobic dance and running etc.

- High-quality efficacy evidence, but not as much as for CBT

- Anxiety reduction is rapid and strong

- Does not cause long-term worsening of anxiety like drugs or supplements

- Benefits do not end immediately when exercise is discontinued

- But benefits wane with increasing time away from aerobic exercise

- Rated #3 Biofeedback and relaxation therapies including biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART) and heart rate variability training (HRV)

- Anxiety-lowering effects are more rapid than CBT and effects strengthen with continued practice of home exercises

- Numerous studies demonstrate efficacy of relaxation therapy

- Benefits do not end upon discontinuation of work with a biofeedback clinician

- Benefits wane if people stop doing biofeedback home exercises

- Because this is a potent anxiety-reducing treatment that can work rapidly, it is possible, though not likely to use biofeedback in a way that would interfere with recovery from anxiety similar to what can occur with anti-anxiety drugs. When used appropriately, biofeedback does not cause long-term worsening of anxiety

- Rated #4 Treatments to that optimize sleep such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

- High-quality evidence for anxiety improvement in people who also have insomnia. Improvement in anxiety is predicated upon improving the insomnia

- Benefits can be life long

- Rated #5 Mindfulness-based therapies like mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and meditative practices

- High-quality efficacy evidence, but not as much as for CBT and relaxation therapies like biofeedback

- Evidence suggest that the potency of the anxiety reduction is not as robust as it is for CBT, biofeedback and aerobic exercise

- Anxiety may increase at first, but with continued practice anxiety decreases more and more over time

- Benefits can be life long

- Does not cause long-term worsening of anxiety like drugs and supplements

- Rated #6 Hypnotherapy

- The evidence for efficacy of hypnosis is strongest when hypnosis is used in conjunction with other talk therapies like CBT and exposure therapies

- Dramatic anxiety reductions in some people.

- Potency of immediate anxiety reducing effects can vary based on an individual’s hypnotizability, but it can still work just as well over time in people who are less hypnotizable.

- Benefits can be life long

- Does not cause long-term worsening of anxiety like drugs and supplements

- Rated #7 Ashwagandha, Withania somnifera (not reviewed on this website)

- Less conflicting research compared to other botanicals researched for anxiety disorders like general anxiety disorder

- Lower potential to make anxiety worse

- Minimal anxiety reduction

- Benefits cease upon discontinuation

- Rated #8 CBD, cannabidiol, full-spectrum CBD

- Evidence for benefits in social anxiety disorder is increasing. Evidence for other anxiety disorders is insufficient. See “Are cannabinoids effective for anxiety?”

- High levels of THC in products can cause anxiety

- Potency of anxiety reduction more robust than ashwagandha

- Potential to make anxiety worse is present, but less than with benzodiazepines like Ativan and Valium and potent anxiolytic botanicals like kava and skullcap (scutellaria lateriflora) an herb without much safety data.

- Benefits cease upon discontinuation

- Rated #9 Benzodiazepines—anti-anxiety medications like Valium, Xanax, Halcion, Ativan and Klonopin

- High-quality studies show these intoxicating drugs strongly suppress anxiety levels in the short-term, but lack of evidence of long-term improvement for anxiety disorders

- Strong potential to worsen anxiety. Chronic use of these drugs likely to make anxiety worse in the long run

- These drugs cause dependence and potentially lethal withdrawal symptoms. Clinical guidelines often recommend use to be limited to 4 weeks. Most appropriate use is for limited duration situations like fear of flying or of enclosed spaces such as while in an MRI chamber.

- Benefits cease when medication is discontinued

- Rated #10 Kava kava root, Piper methysticum

- Many studies show the herb can lower anxiety levels but that the herb is ineffective for anxiety disorders like general anxiety disorder

- Studies showing potency similar to benzodiazepines like Xanax

- May require use for unsafe durations and doses to achieve efficacy

- Benefits cease upon discontinuation

- Strong potential to make anxiety worse

- Rated #11 Valerian root, Valeriana officinalis

- Well-studied herb with conflicting evidence of efficacy. Might be as effective as drugs like Valium, but more research is needed. See Plant Valium: Is Valerian Effective for Anxiety?

- Side-effects include anxiety

- Potency of anxiety reduction higher than ashwagandha, might be lower than kava

- Benefits cease upon discontinuation

- Moderate-to-strong potential to worsen anxiety

- Rated #12 5-HTP, 5-hydroxytryptophan

- Small, low-quality studies demonstrating efficacy in people with anxiety and panic

- Low potential to worsen anxiety

- Benefits cease upon discontinuation

- Rated #13 Meditative movement such as tai chi, qi gong and yoga

- Evidence suggests this type of movement is most useful as adjunctive to other therapies such as CBT, exposure therapies and other talk therapies

- Benefit based on continued practice

- Does not cause long-term worsening of anxiety

- Rated #14 Diet and nutrient therapy including probiotics and anti-inflammatory diets low in processed foods

- Evidence is based on studies which show lower rates of anxiety in populations consuming lower amounts of processed inflammatory foods and small studies using probiotics to treat anxiety

- Benefits last as long as one maintains dietary modifications

- Does not cause long-term worsening of anxiety

Most health-promoting to least health-promoting anxiety treatments, taking into account the number of studies showing added health benefits of the treatment aside from benefits for anxiety and noting any associated risks. Items 1 through 8 have minimal to no safety issues:

- Rated #1 Aerobic exercise such as swimming, aerobic dance and running etc.

- Overuse injuries are possible, but studies show that exercise is very safe and that inactivity can be as risky as smoking cigarettes

- Rated #2 Treatments that optimize sleep such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

- There is robust, high-quality evidence that getting better sleep optimizes overall health

- Virtually no safety risk to this treatment

- Rated #3 Meditative movement such as tai chi, qi gong and yoga

- Injury is unlikely and evidence of overall health benefits is robust

- Rated #4 Diet and nutrient therapy including probiotics and anti-inflammatory diets low in processed foods

- Evidence is overwhelming that eating a poor diet is harmful to health and that even making small changes can have enormous health benefits

- Potential risk exists for supplementation including poor quality probiotic supplements which might contain pathogenic bacteria instead of healthful strains. For people who do not consult qualified healthcare providers, there’s a risk of taking harmful doses of mineral or vitamins

- May trigger eating disorders like orthorexia, anorexia or bulimia

- Rated #5 Mindfulness-based therapies like mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and meditative practices

- There is strong evidence that mindfulness has abundant health benefits and essentially no health risks

- Rated #6 Biofeedback and relaxation therapies including biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART) and heart rate variability training

- These treatments reduce stress and heart rate variability training can improve cardiovascular health. Low heart rate variability is associated with shortened lifespan

- Stress reduction through BART is also helpful for depression and insomnia

- There are only health benefits and no health risks associated with these treatments

- Rated #7 Talk therapy (cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT)

- Counseling—regardless of the modality is likely to promote health by lowering stress and has no health risks

- Rated #8 Hypnotherapy

- No known health risks

- It’s possible that when recalling past events while in a state of hypnosis that the details of the recalled memories may be altered. But our memory can be altered each time we recall an event whether in hypnosis or not.

The following anxiety treatments have safety risks with the risk increasing from item 9 to item 16. List takes into account the number of studies and the seriousness of the treatment’s possible adverse effects:

- Rated #9 CBD, cannabidiol, pure CBD or full spectrum CBD WITH VERY LOW AMOUNTS OF THC in oral forms

- High-quality studies using pure pharmaceutical grade CBD exist which suggest safety. See “How Safe are Cannabinoids?”

- Safety data from studies on non-pharmaceutical CBD extends out to 6 weeks

- Rated #10 Valerian root, Valeriana officinalis

- Though valerian is one of the best studied botanicals, there is insufficient reliable information available about the safety when used for longer than 6 weeks. But some authoritative sources say it’s not been shown safe for more than one month

- The longer it is used and the higher its dose the more likely that one could get side-effects like withdrawal symptoms when the supplement is stopped. For more on valerian safety see “Is Valerian Safe?”

- Rated #11 Ashwagandha, Withania somnifera (not reviewed on this website)

- In April 2023, Denmark banned ashwagandha citing a 2020 finding by the Danish Technical University (DTU) that ashwagandha has a possibly harmful effect on thyroid and sex hormones and potential to induce abortions. The herb’s ability to raise testosterone levels is a risk for men with prostate problems like hyperplasia (BPH) or prostate cancer.

- Safety data is limited. There are studies where it has been used in appropriate doses with apparent safety for up to 6 months, but typically the supplement is not taken for longer than 12 weeks

- Possible safety issues include those relating to liver toxicity and autoimmune diseases and thyroid health

- Like most of the supplements listed on this website, ashwagandha is not safe to be used in pregnancy. Danish experts assert that the herb may cause abortions.

- A 2023 article in McGill University’s Office for Science and Society tells why the herb was banned in Denmark.

- Rated #12 Benzodiazepines used for less than a few days—Benzodiazepines are anti-anxiety medications like Valium, Xanax, Halcion, Ativan and Klonopin

- Rated #13 Full spectrum CBD WITH LARGE AMOUNTS OF THC

- High-THC products run the risk of numerous side-effects, including addictive potential and making anxiety worse. See “How Safe are Cannabinoids?”

- Rated #14 Kava kava root, Piper methysticum

- Because it could take weeks to be effective, it might not work for short-term use. The health risk of long-term use outweigh benefits

- (See section above “Kava’s Potential Health Risks“)

- Rated #15 Benzodiazepines used long-term—Benzodiazepines are anti-anxiety medications like Valium, Xanax, Halcion, Ativan and Klonopin

- Use of these medications for longer than a few weeks likely unsafe

- Use beyond 6 weeks notoriously unsafe. See “Is Valerian Safe?” and “Benzodiazepine Risks: Are You Aware of the Possible Risks from Taking Benzodiazepines?”

- Anxiety is not cured by anti-anxiety medication. These medications when used long-term are addictive and have potentially lethal withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms include rebound anxiety. Many physicians are relunctant to prescribe benzodiazepines long-term and instead prescribe selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like Paxil for patients with anxiety. For more information about SSRIs click this link: How safe are 5-HTP supplements?

- Rated #16 Inhaled forms of any type of CBD

- Inhaled products are unsafe see “How Safe are Inhaled Cannabinoids?”

_____________________________________________________

Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before stopping or starting any medications or supplements.

To find out how Mood Change Medicine helps people with stress and anxiety, click link below:

Do Kava’s Potential Benefits for Depression Outweigh Risks?

There may be only a single study that evaluated the use of kava in depressed patients. 91

A small, 3-week study 92 did find a benefit for depression and anxiety. But, the depressed participants in the study also had anxiety. It is likely that any treatment that improves anxiety will also help depression, regardless of the treatment’s effect on depression. That’s why this study fails to provide evidence that non-anxious people with depression can be helped by kava.

More to the point, one small positive study in depressed people is insufficient to prove that kava is effective for depression.

There are many proven depression treatments with no safety risks that can also reduce anxiety. For example, the gold-standard, first-line treatment for both anxiety and depression is a talk therapy—cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

To find out how effective talk therapy is for healing depression, click link below:

CBT First on List for Depression and Anxiety

To find out how counseling methods like CBT act on the brain to heal anxiety and depression click link below:

Talk Therapy Changes the Brain with Lasting Benefits

And there are other forms of talk therapy that are proven effective for depression

The evidence-based counseling techniques for unipolar depression that are endorsed by psychologists include:

- Behavior Activation (BA)

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

Kava Might Make Depression Worse

Kava, depending on dose, can be intoxicating. Intoxicating substances have addictive potential. Similar to anti-anxiety medications—benzodiazepines like Xanax and Ativan—kava works on the GABA system. Gamma-aminobutyric acid or GABA is a calming neurotransmitter that slows the brain by blocking signals in the central nervous system. Benzodiazepines like Xanax and Ativan are medications known to worsen depression. “Long-term benzodiazepine use can contribute to depression and increased anxiety” according to 2021 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association. 93

Kava’s intoxicating effects could theoretically pose an increased risk for suicide like alcohol and drugs can. Attempting suicide is something that people regret instantaneously when they realize what they are doing, as did one survivor, Kevin Hines. In video link below, Kevin tells his miraculous story of survival.

Kevin is living proof that no matter how much pain we’re in, no matter how hopeless life may feel when we’re in depression’s grip, no one knows what the future may bring. If Kevin hadn’t survived, he would’ve missed out on what turned out to be his life purpose, giving people who are in a lot of pain hope for a brighter future. Depression makes life seem hopeless, but the truth is people with health challenges like depression can and do get better.

If you feel in danger of attempting to end your life, PLEASE call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 (United States phone number).

Intoxicating substances can be a great hindrance to healing from depression. Traditional users of kava who consume it in large amounts may become apathetic. 94 Studies have shown that depression causes apathy and kava might make it worse. Depression dampens areas of the brain we need to help us get out of depression and kava could exacerbate the problem.

Kava intoxication theoretically could dampen parts of the brain needed to defeat depression, further decrease motivation, interfere with solving problems, making it even harder for depressed people to do the things that can help bring feelings of low mood to an end. Intoxication from any substance can interfere with the proven methods of treating depression listed above.

Given that kava might work similarly to anti-anxiety pharmaceuticals which can promote depression, so might kava run the risk of promoting depression in the long run. When one combines kava’s potential to worsen depression, the lack of evidence for its potential to improve depression, its uncertain safety profile with the existence of completely safe and proven depression treatments, then clearly kava’s benefits don’t outweigh its risks.

If one desires to take a supplement for depression, there are supplements other than kava that have better evidence of efficacy that can help without running the risk of making depression worse. For example, the botanical medicine St. John’s wort is shown to be as effective as anti-depressant medications.

(See “St. John’s Wort: Backyard Weed as Potent as Prozac”)

Many people cannot take St. John’s wort because it can dangerously interact with a number of drugs. (See “St. John’s Wort Safety”) There are other supplements with evidence of superior effectiveness for depression compared to that of kava—supplements that don’t run the risk of making depression worse and don’t have the the propensity to interact with all the drugs that interact with St. John’s wort.

(See “5-HTP: Are antidepressants effective, and if so why?”)

But be assured that no one must take supplements to defeat depression. The article, “St. John’s Wort: Getting its Benefits without the Drawbacks” explains how to break free of depression without tablets or tinctures.

To find out how Mood Change Medicine helps people with depression, click link below:

Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for medical advice.

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- “Kava Kava”, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet ]. Last Update: April 10, 2018. Accessed January 26, 2024. ↩︎

- Schmidt M. “German Court Ruling Reverses Kava Ban; German Regulatory Authority Appeals Decision.” HerbalEGram. 2014;11(7). ↩︎

- Kuchta K, Schmidt M, Nahrstedt A. “German Kava Ban Lifted by Court: The Alleged Hepatotoxicity of Kava (Piper methysticum) as a Case of Ill-Defined Herbal Drug Identity, Lacking Quality Control, and Misguided Regulatory Politics.” Planta Med. 2015;81(18):1647-53. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23(6):424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, et al. “Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: A 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;54(3):288-297. doi: 10.1177/0004867419891246. PMID: 31813230. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Escher M, Desmeules J, Giostra E, Mentha G. “Hepatitis associated with Kava, a herbal remedy for anxiety.” BMJ 2001;322:139. View abstract. ↩︎

- Russmann S, Lauterburg BH, Helbling A. “Kava hepatotoxicity [letter]”. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:68-9. View abstract. ↩︎

- Escher M, Desmeules J, Giostra E, Mentha G. “Hepatitis associated with Kava, a herbal remedy for anxiety.” BMJ 2001;322:139. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Stough C, Teschke R, et al. “Kava for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder RCT: analysis of adverse reactions, liver function, addiction, and sexual effects.” Phytother Res. Nov 2013;27(11): 1723-1728. ↩︎

- Lehrl S. “Clinical efficacy of kava extract WS 1490 in sleep disturbances associated with anxiety disorders. Results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial” J Affect Disord. 2004 Feb;78(2):101-10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00238-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] Erratum in: J Affect Disord. 2004 Dec;83(2-3):287. PMID: 14706720. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, Savage KM, Holmes O, Murphy J, Macdonald P, Short A, Nazareth S, et al. “Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: a 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020. 54(3):288–297. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- Stickel, F., Baumuller, H. M., Seitz, K., Vasilakis, D., Seitz, G., Seitz, H. K., and Schuppan, D. “Hepatitis induced by Kava (Piper methysticum rhizoma).” J Hepatol. 2003;39(1):62-67. View abstract. ↩︎

- Becker MW, Lourencone EMS, De Mello AF, et al. “Liver transplantation and the use of KAVA: Case report.” Phytomedicine. Mar 15 2019;56:21-26. ↩︎

- Yamazaki Y, Hashida H, Arita A, et al. “High dose of commercial products of kava (Piper methysticum) markedly enhanced hepatic cytochrome P450 1A1 mRNA expression with liver enlargement in rats.” Food Chem Toxicol. Dec 2008;46(12):3732-3738. ↩︎

- Russmann S, Lauterburg BH, Helbling A. “Kava hepatotoxicity [letter].” Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:68-9. View abstract. ↩︎

- Li XZ, Ramzan I. “Role of ethanol in kava hepatotoxicity.” Phytother Res. 2010;24:475-80. View abstract. ↩︎

- Yang X, Salminen WF. “Kava extract, an herbal alternative for anxiety relief, potentiates acetaminophen-induced cytotoxicity in rat hepatic cells.” Phytomedicine. 2011 May 15;18(7):592-600. ↩︎

- Gurley BJ, Fifer EK, Gardner Z. “Pharmacokinetic herb-drug interactions (part 2): drug interactions involving popular botanical dietary supplements and their clinical relevance.” Planta Med. Sep 2012;78(13):1490-1514. ↩︎

- Strahl S, Ehret V, Dahm HH, Maier KP. “[Necrotizing hepatitis after taking herbal medication].” Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1998;123:1410-4. View abstract. ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). “Kava: A Review of the Safety of Traditional and Recreational Beverage Consumption. Volume 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation; Rome, Italy: 2016.” pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). “Kava: A Review of the Safety of Traditional and Recreational Beverage Consumption. Volume 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation; Rome, Italy: 2016.” pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). “Kava: A Review of the Safety of Traditional and Recreational Beverage Consumption. Volume 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation; Rome, Italy: 2016.” pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Teschke, R., Genthner, A., and Wolff, A. “Kava hepatotoxicity: comparison of aqueous, ethanolic, acetonic kava extracts and kava-herbs mixtures.” J.Ethnopharmacol. 6-25-2009;123(3):378-384. View abstract. ↩︎

- Teschke R, Sarris J, Schweitzer I. “Kava hepatotoxicity in traditional and modern use: the presumed Pacific kava paradox hypothesis revisited.” Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(2):170-4. View abstract. ↩︎

- Li XZ, Ramzan I. “Role of ethanol in kava hepatotoxicity.” Phytother Res. 2010;24:475-80. View abstract. ↩︎

- Li XZ, Ramzan I. “Role of ethanol in kava hepatotoxicity.” Phytother Res. 2010;24:475-80. View abstract. ↩︎

- Teschke R. “Kava hepatotoxicity: pathogenetic aspects and prospective considerations.” Liver Int. 2010;30(9):1270-9. View abstract. ↩︎

- Stickel, F., Baumuller, H. M., Seitz, K., Vasilakis, D., Seitz, G., Seitz, H. K., and Schuppan, D. “Hepatitis induced by Kava (Piper methysticum rhizoma).” J Hepatol. 2003;39(1):62-67. View abstract. ↩︎

- Yang X, Salminen WF. “Kava extract, an herbal alternative for anxiety relief, potentiates acetaminophen-induced cytotoxicity in rat hepatic cells.” Phytomedicine. 2011 May 15;18(7):592-600. ↩︎

- Russmann S, Lauterburg BH, Helbling A. “Kava hepatotoxicity [letter].” Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:68-9. View abstract. ↩︎

- Schelosky L, Raffaup C, Jendroska K, Poewe W. “Kava and dopamine antagonism.” J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:639-40. View abstract. ↩︎

- Meseguer E, Taboada R, Sanchez V, et al. “Life-threatening parkinsonism induced by kava-kava.” Mov Disord. 2002;17:195-6. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, et al. “Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: A 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;54(3):288-297. doi: 10.1177/0004867419891246. Epub 2019 Dec 8. PMID: 31813230. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- Leung, N. “Acute urinary retention secondary to kava ingestion.” Emerg Med Australas. 2004;16(1):94. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, et al. “Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: A 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;54(3):288-297. doi: 10.1177/0004867419891246. Epub 2019 Dec 8. PMID: 31813230. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- Garner LF, Klinger JD. “Some visual effects caused by the beverage kava.” J Ethnopharmacol. 1985;13:307-311.. View abstract. ↩︎

- Wainiqolo I, Kafoa B, Kool B, et al. “Driving following kava use and road traffic injuries: a population-based case-control study in Fiji (TRIP 14).” PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149719. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Ketola RA, Viinamäki J, Rasanen I, Pelander A, Goebeler S. “Fatal kavalactone intoxication by suicidal intravenous injection.” Forensic Sci Int. 2015;249:e7-e11. View abstract. ↩︎

- Shinomiya K, Inoue T, Utsu Y, Tokunaga S, Masuoka T, Ohmori A. et al. “Effects of kava-kava extract on the sleep–wake cycle in sleep-disturbed rats.” Psychopharmacology. 2005;180(3):564–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Baum SS, Hill R, Rommelspacher H. “Effect of kava extract and individual kavapyrones on neurotransmitter levels in the nucleus accumbens of rats.” Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1998 Oct;22(7):1105-20. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(98)00062-1. PMID: 9829291 ↩︎

- Lehrl S. “Clinical efficacy of kava extract WS 1490 in sleep disturbances associated with anxiety disorders. Results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial” J Affect Disord. 2004 Feb;78(2):101-10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00238-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] Erratum in: J Affect Disord. 2004 Dec;83(2-3):287. PMID: 14706720. ↩︎

- Jacobs BP, Bent S, Tice JA, Blackwell T, Cummings SR. “An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia.” Medicine (Baltimore). Jul 2005;84(4):197-207. ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Jacobs BP, Bent S, Tice JA, Blackwell T, Cummings SR. “An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia.” Medicine (Baltimore). Jul 2005;84(4):197-207. ↩︎

- Howatson G, Bell PG, Tallent J, et al. “Effect of tart cherry juice (Prunus cerasus) on melatonin levels and enhanced sleep quality.” Eur J Nutr. 2011;51:909-16. View abstract. ↩︎

- Pigeon WR, Carr M, Gorman C, Perlis ML. “Effects of a tart cherry juice beverage on the sleep of older adults with insomnia: a pilot study.” J Med Food. 2010;13:579-83. View abstract. ↩︎

- Herhaus B, Kalin A, Gouveris H, Petrowski K. “Mobile Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Improves Autonomic Activation and Subjective Sleep Quality of Healthy Adults – A Pilot Study.” Front Physiol. 2022 Feb 17;13:821741. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.821741. PMID: 35250623; PMCID: PMC8892186. ↩︎

- Lehrl S. “Clinical efficacy of kava extract WS 1490 in sleep disturbances associated with anxiety disorders. Results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial” J Affect Disord. 2004 Feb;78(2):101-10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00238-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] Erratum in: J Affect Disord. 2004 Dec;83(2-3):287. PMID: 14706720. ↩︎

- Witte S, Loew D, Gaus W. “Meta-analysis of the efficacy of the acetonic kava-kava extract WS1490 in patients with non-psychotic anxiety disorders.” Phytother Res. 2005. 19(3):183-8. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Stough C, Bousman CA, et al. “Kava in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.“ J Clin Psychopharmacol. Oct 2013;33(5):643-648. ↩︎

- Jacobs BP, Bent S, Tice JA, Blackwell T, Cummings SR. “An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia.” Medicine (Baltimore). Jul 2005;84(4):197-207. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, Savage KM, Holmes O, Murphy J, Macdonald P, Short A, Nazareth S, et al. Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: a 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020. 54(3):288–297. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- Connor KM, Payne V, Davidson JR. “Kava in generalized anxiety disorder: three placebo-controlled trials.” Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;21:249-53. View abstract. ↩︎

- Zhang W, Yan Y, Wu Y, et al. “Medicinal herbs for the treatment of anxiety: A systematic review and network meta-analysis.” Pharmacol Res. 2022;179:106204. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Scholey A, Schweitzer I, et al. “The acute effects of kava and oxazepam on anxiety, mood, neurocognition; and genetic correlates: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study.” Psychopharmacol. 2012 May;27(3):262-9. ↩︎

- “Kava”, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine, National Institutes of Health Last Updated: August 2020, accessed January 2024. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Stough C, Bousman CA, et al. “Kava in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.“ J Clin Psychopharmacol. Oct 2013;33(5):643-648. ↩︎

- Pittler MH, Ernst E (2000) “Efficacy of kava extract for treating anxiety: Systematic review and metaanalysis” J Clin Psychopharmacol. 20:84-9. ↩︎

- Witte S, Loew D, Gaus W. “Meta-analysis of the efficacy of the acetonic kava-kava extract WS1490 in patients with non-psychotic anxiety disorders.” Phytother Res. 2005 Mar;19(3):183-8. ↩︎

- Jacobs BP, Bent S, Tice JA, Blackwell T, Cummings SR. “An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia.” Medicine (Baltimore). Jul 2005;84(4):197-207. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, Savage KM, Holmes O, Murphy J, Macdonald P, Short A, Nazareth S, et al. “Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: a 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020. 54(3):288–297. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- Sarris J, LaPorte E, Schweitzer I. “Kava: A Comprehensive Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Psychopharmacology.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;45(1):27-35. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.522554 ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, Savage KM, Holmes O, Murphy J, Macdonald P, Short A, Nazareth S, et al. “Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: a 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020. 54(3):288–297. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- Sarris J, Marx W, Ashton MM, et al. “Plant-based Medicines (Phytoceuticals) in the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: A Meta-review of Meta-analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials: Les médicaments à base de plantes (phytoceutiques) dans le traitement des troubles psychiatriques: une méta-revue des méta-analyses d’essais randomisés contrôlés.” Can J Psychiatry. 2021 Oct;66(10):849-862. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23(6):424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J. 2016. “Kava in the treatment of anxiety. In: Gerbarg P, Brown R, Muskin P, ediors. Complementary and integrative treatments in psychiatric practice.” New York: American Psychiatric Publishing. Google Scholar ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23(6):424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23(6):424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- Zhang W, Yan Y, Wu Y, et al. “Medicinal herbs for the treatment of anxiety: A systematic review and network meta-analysis.” Pharmacol Res. 2022;179:106204. View abstract. ↩︎

- Smith K, Leiras C. “The effectiveness and safety of Kava Kava for treating anxiety symptoms: A systematic review and analysis of randomized clinical trials.” Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;33:107-117. View abstract. ↩︎

- Volz HP, Kieser M. “Kava-kava extract WS 1490 versus placebo in anxiety disorders–a randomized placebo-controlled 25-week outpatient trial.” Pharmacopsychiatry. 1997;30:1-5. View abstract. ↩︎

- Jacobs BP, Bent S, Tice JA, Blackwell T, Cummings SR. “An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia.” Medicine (Baltimore). Jul 2005;84(4):197-207. ↩︎

- Boerner RJ, Sommer H, Berger W, et al. “Kava-Kava extract LI 150 is as effective as opipramol and buspirone in generalised anxiety disorder–an 8-week randomized, double-blind multi-centre clinical trial in 129 out-patients.” Phytomedicine. 2003;10 Suppl 4:38-49. View abstract. ↩︎

- Smith K, Leiras C. “The effectiveness and safety of Kava Kava for treating anxiety symptoms: A systematic review and analysis of randomized clinical trials.” Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;33:107-117. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Scholey A, Schweitzer I, et al. “The acute effects of kava and oxazepam on anxiety, mood, neurocognition; and genetic correlates: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study.” Psychopharmacol. 2012 May;27(3):262-9. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Stough C, Bousman CA, et al. “Kava in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study.“ J Clin Psychopharmacol. Oct 2013;33(5):643-648. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23(6):424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Byrne GJ, Bousman CA, Cribb L, Savage KM, Holmes O, Murphy J, Macdonald P, Short A, Nazareth S, et al. “Kava for generalised anxiety disorder: a 16-week double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study.” Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020. 54(3):288–297. View PubMed Web of Science ®Google Scholar ↩︎

- Sarris J, Ravindran A, Yatham LN, et al. “Clinician guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders with nutraceuticals and phytoceuticals: The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Taskforce.” World J Biol Psychiatry. 2022;23(6):424-455. View abstract. ↩︎

- “Kava”. NatMed Pro Therapeutic Research Center database. current through 12/07/2023. Last modified 3/29/2024. Accessed July, 2024. ↩︎

- Ernst E. “Herbal remedies for anxiety – a systematic review of controlled clinical trials.” Phytomedicine. 2006 Feb;13(3):205-8. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Kavanagh DJ, Byrne G, Bone KM, Adams J, Deed G. “The Kava Anxiety Depression Spectrum Study (KADSS): a randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial using an aqueous extract of Piper methysticum.” Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009 Aug;205(3):399-407. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1549-9. Epub 2009 May 9. PMID: 19430766. ↩︎

- Sarris J, Kavanagh DJ, Byrne G, Bone KM, Adams J, Deed G. “The Kava Anxiety Depression Spectrum Study (KADSS): a randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial using an aqueous extract of Piper methysticum.” Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009 Aug;205(3):399-407. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1549-9. Epub 2009 May 9. PMID: 19430766. ↩︎

- Horowitz MA, Wright JM, Taylor D. “Risks and Benefits of Benzodiazepines.” JAMA. 2021;325(21):2208–2209. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4513 ↩︎

- Cawte, J. “Parameters of kava used as a challenge to alcohol”. Aust.N.Z.J Psychiatry .1986;20(1):70-76. View abstract. ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.