By using MoodChangeMedicine.com, you agree to accept this website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

May 13, 2024

By Joie Meissner ND, BCB-L

Evidence is growing that exercise may be a more effective mood booster than SSRI antidepressants like Prozac and it doesn’t carry potentially dangerous drug side effects.

The most common antidepressant drugs got bottom-of-the barrel results in a landmark systematic review comparing the drugs’ effect on depression with that of the talk-therapy CBT and a range of exercise modalities, according to data published by the prestigious British Medical Journal in February 2024.

“We found some forms of exercise to have stronger effects than SSRIs alone,” wrote the researchers who conducted a meta-analysis of 218 studies with a total of 14,170 depressed participants getting various treatments including antidepressants, CBT and exercise. 1

Data showed CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) and exercise to be considerably more effective than SSRIs. The effects were medium for cognitive behavioral therapy alone and small for SSRIs alone, comparable to what other meta-analyses—statistical analyses of data pooled from numerous studies—have found for SSRIs. 2, 3 The researchers wrote: “Exercise may therefore be considered a viable alternative to drug treatment.”

Always consult a physician or qualified healthcare provider before making changes to your medications.

The researchers called for a reappraisal of how depression patients are treated saying—in what can only be described as an understatement—that relegating exercise to the category of “complementary or alternative treatment” . . . “may be overly conservative. Instead, guidelines for depression ought to include prescriptions for exercise.” 4

For patients who prefer not to engage in psychotherapy such as CBT exercise may provide an alternative, said the researchers who noted that CBT was comparably effective to exercise. The researchers cautioned that the quality of the data for exercise was not as robust as for that of CBT. 5

People who engaged in higher levels of physical activity versus lower levels of activity were 26% less likely to become anxious, according to a 2019 meta-analysis including 75,831 participants. The risk of developing agoraphobia and PTSD was diminished by 58% and 43% respectively. 6

Exercise is not only useful for prevention of anxiety, it can treat it too. Exercise programs “are a viable treatment option for the treatment of anxiety,” concluded researchers in a 2018 systematic review of 15 studies including 675 participants with anxiety. “High intensity exercise regimens were found to be more effective than low intensity regimens.” 7

In “other countries such as Australia, lifestyle management is recommended as the first-line treatment approach” for mental health conditions including depression and anxiety, said the researchers of a 2023 systematic study that pooled data from 1039 randomized controlled trials spanning 128,119 adults with mental health disorders and various chronic diseases. The study found that all forms of exercise improved mental health. People who did higher-intensity exercise had the biggest reductions in anxiety and depression. “Physical activity should be a mainstay approach in the management of depression, anxiety and psychological distress,” the researchers concluded. 8

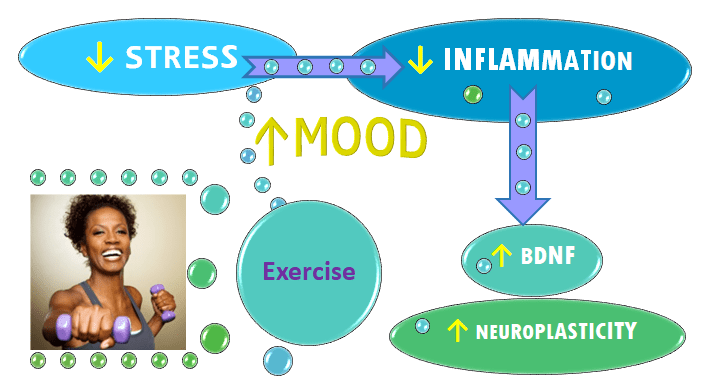

Exercise boosts your mood, reduces stress and inflammation, 9 and raises levels of a key brain chemical called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) 10, 11 that boosts neuroplasticity by promoting the growth of new neurons and new connections between these cells. 12, 13

Inflammation has been implicated as an important part of the mechanism driving anxiety and depression. 14, 15, 16, 17 Hyperactivation of inflammatory proteins is linked to depression, anxiety and a host of other conditions. 18

Studies have shown an association between inflammation and how our brains process emotional information. 19

Inflammation and its cascade of biochemical consequences including decreased neuroplasticity might be the reason that antidepressants don’t work that well in patients with high levels of inflammation. 20 And it might also explain why patients that have elevated inflammation may not respond to talk therapy. 21, 22, 23, 24, 25

Changes in BDNF are implicated in the development of anxiety and depression via its effects on neuroplasticity of the brain. 26, 27

Scientists postulate that decreased production of BDNF contributes to depression by impairing regeneration of brain tissue. 28 Increased production of BDNF plays a role in how the brain heals from depression by facilitating regeneration of these tissues. 29 Such regeneration is a crucial aspect of neuroplasticity, which is part of the amazing resilience of the brain.

Substances produced by exercising our muscles mediate BDNF’s impact in the brain and highlight its broad role in neuroplasticity. 30

Even a single session of exercise raises BDNF, which has been shown to bring a broad range of positive results for mood, learning and physical health, according to 2015 meta-analysis of 29 studies encompassing 1,111 subjects, some of whom had major depression. The researchers concluded that “exercise may help rescue the low resting BDNF levels often observed in depressed patients and exercise produces effects in a similar range to those of antidepressants.” 31

Exercise appeared to reverse the characteristic atrophy of the hippocampus seen in long-term depression; the study authors wrote. And BDNF induced by exercise “helps reduce the effects of specific stressors, including oxidative DNA changes and disruption of synaptic plasticity from sleep deprivation,” the authors wrote citing other research. 32

Preliminary results from the study “raised the question whether regular exercise may have greater effects in psychiatric than healthy participants.” They found that subjects with major depression or panic showed more than double the increase in BDNF compared to healthy subjects. 33

Even slow, mindfulness-based movement such as yoga, tai chi and qi gong can significantly boost BDNF levels, according to a 2020 analysis of eleven randomized controlled trials including 479 patients with various conditions including depression. 34

The effects of exercise to promote new growth of neurons is boosted when combined with dietary modifications. 35 Combining exercise along with a diet containing omega-3 (DHA) found in fish oil, boosts BDNF’s neuroplastic effects in the brain. 36

Questions about Mood Change Medicine? Click link below:

Care informed by the understanding that emotional and physical wellbeing are deeply connected

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

By using this website, you agree to accept MoodChangeMedicine.com website’s terms of use, which can be viewed here.

Citations

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. “Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis.” Lancet. 2018; 391:1357–66. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. pmid:29477251 PubMed Google Scholar ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- Noetel M, Sanders T, Gallardo-Gómez D, Taylor P, del Pozo Cruz B, van den Hoek D et al. “Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” BMJ 2024; 384 :e075847 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075847 ↩︎

- Schuch FB, Stubbs B, Meyer J, Heissel A, Zech P, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, et al. “Physical activity protects from incident anxiety: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.” Depress Anxiety. 2019 Sep;36(9):846-858. doi: 10.1002/da.22915. Epub 2019 Jun 17. PMID: 31209958. doi/10.1002/da.22915 ↩︎

- Aylett E, Small N, Bower P. “Exercise in the treatment of clinical anxiety in general practice – a systematic review and meta-analysis.” BMC Health Serv Res. 2018. Jul 16;18(1):559. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3313-5. PMID: 30012142; PMCID: PMC6048763. ↩︎

- Singh B, Olds T, Curtis R, Dumuid D, et al. “Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews.” Br J Sports Med. 2023 Sep;57(18):1203-1209. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106195. Epub 2023 Feb 16. PMID: 36796860; PMCID: PMC10579187. ↩︎

- Stoyan Dimitrov, Elaine Hulteng, and Suzi Hong. “Inflammation and exercise: Inhibition of monocytic intracellular TNF production by acute exercise via β2-adrenergic activation” by in Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. Published online December 21 2016 doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.017 ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. “A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor.” J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Jan;60:56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. Epub 2014 Oct 12. PMID: 25455510; PMCID: PMC4314337. ↩︎

- Gomutbutra P, Yingchankul N, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn S, Srisurapanont M. “The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials.” Front Psychol. 2020 Sep 15;11:2209. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02209. PMID: 33041891; PMCID: PMC7522212. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, O’Neil A, et al. “So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from?” BMC Med. 2013 Sep 12;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-200. PMID: 24228900; PMCID: PMC3846682. ↩︎

- Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Papageorgiou C, Tsetsekou E, Soldatos C, Stefanadis C. “Anxiety in relation to inflammation and coagulation markers, among healthy adults: the ATTICA study.” Atherosclerosis. 2006 Apr;185(2):320-6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.001. Epub 2005 Jul 11. PMID: 16005881 ↩︎

- Hu P, Lu Y, Pan BX, Zhang WH. “New Insights into the Pivotal Role of the Amygdala in Inflammation-Related Depression and Anxiety Disorder.” Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 21;23(19):11076. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911076. PMID: 36232376; PMCID: PMC9570160. ↩︎

- Hassamal, Sameer. “Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories.” Front. Psychiatry. 10 May 2023. Sec. Molecular Psychiatry Volume 14 – 2023. frontiersin.psychiatry/10.3389. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1130989 ↩︎

- Maydych V. “The Interplay Between Stress, Inflammation, and Emotional Attention: Relevance for Depression.” Front Neurosci. 2019 Apr 24;13:384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00384. PMID: 31068783; PMCID: PMC6491771. ↩︎

- Cowen PJ, Browning M. “What has serotonin to do with depression?” World Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;14(2):158-60. doi: 10.1002/wps.20229. PMID: 26043325; PMCID: PMC4471964. ↩︎

- S.R. Chamberlain, J. Cavanagh, P. de Boer, V. Mondelli, D.N. Jones, W.C. Drevets, et al.

“Treatment-resistant depression and peripheral C-reactive protein.” Br. J. Psychiatry. 2019. 214 (1) (2019), pp. 11-19 ↩︎ - Strawbridge R, Marwood L, King S, et al. “Inflammatory Proteins and Clinical Response to Psychological Therapy in Patients with Depression: An Exploratory Study.” J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 2;9(12):3918. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123918. PMID: 33276697; PMCID: PMC7761611. ↩︎

- M. Maes, E. Bosmans, R. De Jongh, G. Kenis, E. Vandoolaeghe, H. Neels. “Increased serum IL-6 and IL-1 receptor antagonist concentrations in major depression and treatment resistant depression.” Cytokine. 9 (11) (1997), pp. 853-858 ↩︎

- S.M. O’Brien, P. Scully, P. Fitzgerald, L.V. Scott, T.G. Dinan. “Plasma cytokine profiles in depressed patients who fail to respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy.” J. Psychiatric Res. 41 (3–4) (2007), pp. 326-331 ↩︎

- Lopresti AL. “Cognitive behaviour therapy and inflammation: A systematic review of its relationship and the potential implications for the treatment of depression.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;51(6):565-582. doi:10.1177/0004867417701996 ↩︎

- Miao Z, Wang Y, Sun Z. “The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF.” Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Feb 18;21(4):1375. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041375. PMID: 32085670; PMCID: PMC7073021. ↩︎

- Kurita M, Nishino S, Kato M, Numata Y, Sato T. “Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels predict the clinical outcome of depression treatment in a naturalistic study.” PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039212. Epub 2012 Jun 27. PMID: 22761741; PMCID: PMC3384668 ↩︎

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM. “A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders.” Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Jun 15;59(12):1116-27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. Epub 2006 Apr 21. PMID: 16631126. ↩︎

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM. “A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders.” Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Jun 15;59(12):1116-27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. Epub 2006 Apr 21. PMID: 16631126. ↩︎

- Appelbaum, L.G., Shenasa, M.A., Stolz, L. et al. “Synaptic plasticity and mental health: methods, challenges and opportunities.” Neuropsychopharmacol. 48, 113–120 (2023). nature.com doi.org/10.1038/s41386-022-01370-w ↩︎

- Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. “A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor.” J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Jan;60:56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. Epub 2014 Oct 12. PMID: 25455510; PMCID: PMC4314337. ↩︎

- Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. “A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor.” J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Jan;60:56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. Epub 2014 Oct 12. PMID: 25455510; PMCID: PMC4314337. ↩︎

- Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. “A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor.” J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Jan;60:56-64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. Epub 2014 Oct 12. PMID: 25455510; PMCID: PMC4314337. ↩︎

- Gomutbutra P, Yingchankul N, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn S, Srisurapanont M. “The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials.” Front Psychol. 2020 Sep 15;11:2209. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02209. PMID: 33041891; PMCID: PMC7522212. ↩︎

- Gomez-Pinilla F. “The combined effects of exercise and foods in preventing neurological and cognitive disorders.” Prev Med. 2011;52:75–80. 2011 Jun;52 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S75-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.023. Epub 2011 Jan 31. PMID: 21281667; PMCID: PMC3258093. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

- Wu A, Ying Z, Gomez-Pinilla F. “Docosahexaenoic acid dietary supplementation enhances the effects of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition.” Neuroscience. 2008;155:751–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] ↩︎

Discussion

No comments yet.